Human Impact on Ecosystems: A Scientist’s View

The relationship between humanity and the natural world has fundamentally shifted over the past two centuries. What was once a relatively balanced interaction between human societies and their natural environment has transformed into a dominant force reshaping planetary systems at an unprecedented scale and speed. From the microscopic alterations in soil microbial communities to the macroscopic restructuring of entire biomes, human activities now represent the primary driver of ecological change across nearly every terrestrial and marine ecosystem on Earth.

As scientists examine the evidence accumulated through decades of rigorous research, a sobering picture emerges: human civilization operates as a geological force comparable to the great extinction events of Earth’s history. Yet unlike those catastrophic natural phenomena, this transformation unfolds within a timeframe measured in decades rather than millennia, compressed by the explosive growth of industrial economies and human populations. Understanding the mechanisms through which we impact ecosystems—and the cascading consequences that ripple through interconnected natural systems—is essential for developing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The Scope of Human Ecological Footprint

The concept of an ecological footprint quantifies the biologically productive land and water area required to support human consumption patterns and absorb waste products. Current scientific estimates reveal that humanity’s collective footprint exceeds Earth’s biocapacity by approximately 75 percent—meaning we are consuming resources and generating waste at rates that would require 1.75 Earths to sustain indefinitely. This overshoot represents the fundamental driver of ecosystem degradation globally.

The distribution of this impact remains profoundly unequal. High-income nations, comprising roughly 16 percent of global population, consume approximately 80 percent of biocapacity, while lower-income regions experience disproportionate ecological damage. This paradox reflects the economic structures through which wealthy nations externalize environmental costs to less-developed regions through supply chains, resource extraction, and waste dumping. Understanding how humans affect the environment requires examining these economic relationships alongside biophysical mechanisms.

Research from the World Wildlife Fund demonstrates that global wildlife populations have declined by an average of 69 percent since 1970, driven primarily by habitat loss, overexploitation, and pollution—all direct consequences of human economic activity. The Living Planet Index, which tracks vertebrate population trends across thousands of species, documents ecosystem collapse occurring in real-time across multiple continents and ocean basins.

Climate Change and Atmospheric Disruption

Among the most consequential human impacts on ecosystems is the alteration of atmospheric composition through greenhouse gas emissions. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased from 280 parts per million in pre-industrial times to over 420 ppm today—a rate of change approximately 10 times faster than historical natural variations. This rapid atmospheric restructuring drives cascading ecological disruptions across all biomes.

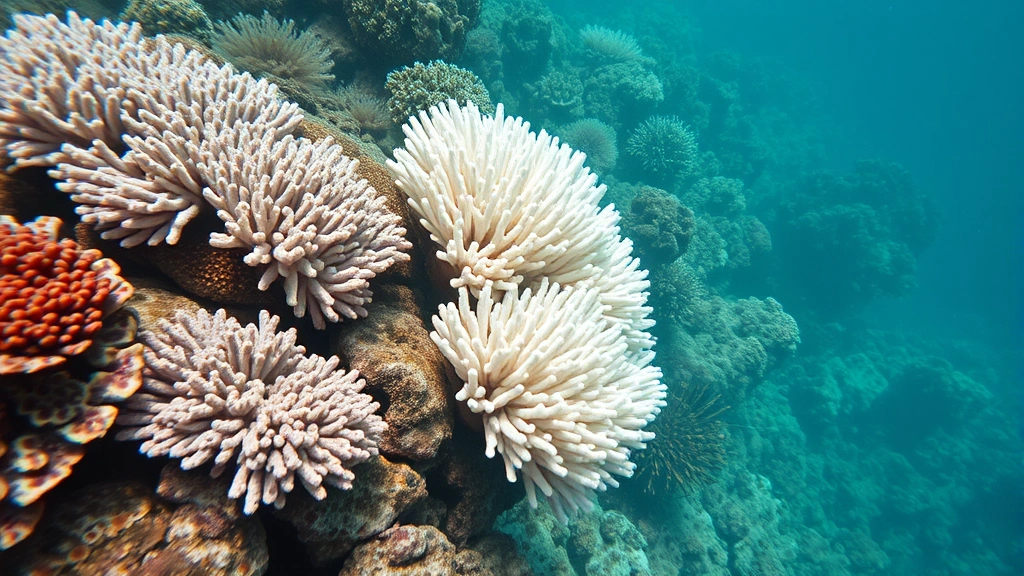

The warming induced by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions fundamentally alters the physical and chemical properties of ecosystems. Temperature shifts disrupt the phenological synchronization—the timing of seasonal events—upon which countless species depend. Migratory birds arrive to breeding grounds only to find food sources have already peaked and declined. Coral reef symbioses break down as temperature stress induces bleaching events that kill the zooxanthellae algae essential to coral nutrition. Permafrost thaw in Arctic regions releases methane and carbon dioxide previously sequestered for millennia, creating positive feedback loops that accelerate warming beyond human emissions alone.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, even with aggressive emissions reductions, Earth’s climate will continue warming for several decades due to the thermal inertia of oceanic systems. This committed warming guarantees substantial additional ecosystem disruption regardless of immediate policy changes, making adaptation alongside mitigation essential for ecological resilience.

Mountain ecosystems face particularly acute climate impacts. As temperatures rise, species migrate upslope seeking cooler conditions, yet alpine regions offer limited upslope habitat before reaching the summit. Entire species assemblages face compression into progressively smaller areas, with many species lacking sufficient habitat above current distribution ranges. Glacial retreat—occurring across 95 percent of monitored glaciers globally—disrupts downstream water availability for billions of people dependent on glacier-fed rivers.

Biodiversity Loss and Species Extinction

The current extinction rate, conservatively estimated at 100 to 1,000 times natural background rates, signals what many scientists term the Sixth Mass Extinction. Unlike previous extinction events driven by volcanic activity, asteroid impacts, or climate oscillations, this extinction unfolds as a direct consequence of single species—humans—restructuring planetary systems according to economic imperatives rather than ecological sustainability.

Habitat destruction accounts for approximately 85 percent of species extinctions, with remaining mortality driven by overexploitation, invasive species, pollution, and climate change. The relationship between human environment interaction and biodiversity loss operates through multiple mechanisms simultaneously. Clearing tropical rainforests for agricultural expansion eliminates habitat for species found nowhere else on Earth—many unknown to science before their extinction. Intensive monoculture agriculture replaces diverse natural communities with single-species crops, eliminating food and shelter for countless dependent species.

The loss of top predators through hunting and habitat destruction cascades through trophic networks, fundamentally restructuring ecosystem dynamics. Wolves eliminated from most of their range allowed deer populations to expand, overgrazing vegetation communities and triggering trophic cascades that alter forest structure, nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration. Reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park provided experimental evidence demonstrating that apex predator restoration triggers ecosystem-wide recovery—a finding with profound implications for conservation strategy.

Pollinator decline represents a particularly concerning manifestation of biodiversity loss with direct economic consequences. Approximately 75 percent of global food crops depend at least partially on animal pollination, yet bee populations have declined precipitously due to pesticide exposure, habitat loss, and disease. Economic valuations of pollination services lost to population declines exceed hundreds of billions of dollars annually, yet these costs remain externalized from agricultural commodity pricing.

Land Use Transformation and Habitat Destruction

Human land use now directly affects approximately 75 percent of Earth’s ice-free terrestrial surface, with only 23 percent of land area remaining in relatively natural condition. This transformation represents perhaps the most visible manifestation of human ecological dominance. Forests that once covered roughly 50 percent of terrestrial land have been reduced to approximately 30 percent, with remaining forests increasingly fragmented into isolated patches incapable of supporting viable populations of large-bodied species requiring extensive ranges.

Agricultural expansion drives the majority of contemporary habitat destruction. Converting natural ecosystems to cropland or pasture eliminates the structural complexity and species diversity that characterize wild communities. A typical agricultural landscape supports 50-90 percent fewer bird species than equivalent natural habitat, with losses concentrated among specialist species unable to tolerate simplified environments. The conversion of 1.5 billion hectares of grasslands to pasture has eliminated herbivore communities that evolved over millions of years, replaced by domesticated cattle that fundamentally alter soil structure, nutrient cycling, and hydrological function.

Urbanization creates additional habitat destruction through direct conversion and fragmentation effects. Cities and their associated infrastructure now cover approximately 1-3 percent of global land area but drive disproportionate ecosystem impacts through habitat fragmentation, pollution, and resource extraction. Urban sprawl fragments remaining natural habitat into progressively smaller patches, reducing genetic diversity within populations and increasing vulnerability to stochastic extinction events. The ecological impacts of cities extend far beyond municipal boundaries through resource extraction networks and waste disposal systems.

Understanding these land transformation processes requires examining the relationship between environment and society through economic and historical perspectives. Colonial and post-colonial land appropriation, structural economic policies favoring resource extraction, and demographic transitions driving agricultural intensification all operate as underlying drivers of contemporary habitat destruction patterns.

Water Systems and Pollution Cascades

Freshwater ecosystems, despite covering less than 1 percent of Earth’s surface, support approximately 10 percent of all species and provide essential services to human populations including drinking water, food production, hydroelectric power, and nutrient cycling. Yet these ecosystems face unprecedented human pressure through direct abstraction, pollution, and climate-driven alterations to precipitation and flow regimes.

Rivers worldwide have been fundamentally restructured through dam construction, water diversion, and pollution inputs. The Colorado River, once flowing to the Pacific Ocean, now desiccates in the desert before reaching its delta due to massive water extraction for irrigation and urban consumption. The Aral Sea, formerly the world’s fourth-largest lake, has shrunk to a fraction of its historical volume due to river diversion for cotton irrigation, creating an ecological catastrophe and regional climate disruption. These examples represent not isolated failures but systematic patterns repeated across continents as human water demand exceeds sustainable renewable supplies.

Chemical pollution of aquatic systems creates biological dead zones where nutrient enrichment from agricultural runoff and sewage discharge triggers eutrophication—excessive algal growth that consumes dissolved oxygen as it decomposes, creating conditions unsuitable for most aquatic life. The Gulf of Mexico dead zone, driven by Mississippi River nutrient loading from Midwestern agriculture, now covers areas exceeding 20,000 square kilometers during peak hypoxic seasons. Similar dead zones exist in the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, and numerous coastal regions globally, representing a systematic failure to internalize agricultural pollution costs.

Plastic pollution has emerged as a dominant feature of aquatic ecosystems globally. Approximately 8 million metric tons of plastic enter oceans annually, fragmenting into microplastics that pervade entire food webs. Microplastics have been detected in deep-sea sediments, polar ice, and within human blood and lung tissue, demonstrating the pervasive nature of this pollution. The persistence of plastic polymers—some requiring centuries to degrade—ensures that current pollution patterns will continue disrupting aquatic ecosystems for generations.

Economic Implications and Ecosystem Services

The economic consequences of ecosystem degradation extend far beyond the direct loss of biological resources. Natural ecosystems provide services—often called ecosystem services—that maintain conditions enabling human civilization. These include climate regulation through carbon sequestration, water purification through filtration and bioaccumulation, soil formation and nutrient cycling, pollination of crops, flood regulation through wetland buffering, and countless others.

Economic valuations of ecosystem services lost to degradation reveal staggering costs. Global ecosystem service losses from habitat destruction exceed 4-20 trillion dollars annually according to United Nations Environment Programme assessments, yet these costs remain largely invisible in conventional economic accounting. A forest provides ecosystem services through carbon sequestration, water filtration, and habitat provision worth thousands of dollars per hectare annually, yet current economic systems value only the timber harvested—typically worth far less. This systematic undervaluation of natural capital relative to extracted resources creates perverse economic incentives favoring ecosystem conversion.

The concept of ecological economics attempts to address these valuation failures by developing frameworks that recognize natural capital as fundamental to all economic activity. Unlike conventional economics treating environment as external to economic systems, ecological economics recognizes that economy operates as a subsystem within finite ecological systems. This perspective reveals that current economic growth models are fundamentally incompatible with planetary boundaries and ecosystem carrying capacity.

Agricultural productivity gains from industrial intensification, achieved through fossil fuel subsidies, chemical inputs, and mechanization, have masked underlying soil degradation and biodiversity loss. Approximately 24 billion tons of fertile soil are lost annually to erosion and degradation, reducing agricultural productivity and requiring ever-increasing chemical inputs to maintain yields. The economic costs of soil loss—estimated at 400 billion dollars annually—dwarf the short-term productivity gains, yet remain externalized from commodity pricing.

Understanding the scientific definition of environment as an integrated system reveals that separating economic valuation from ecological function creates analytical errors with profound policy consequences. When ecosystem services are assigned monetary values, cost-benefit analyses consistently demonstrate that ecosystem preservation provides superior economic returns compared to conversion for resource extraction or development.

Pathways to Ecological Recovery

Despite the severity of contemporary ecosystem degradation, scientific evidence demonstrates that recovery is possible when human pressures are reduced and appropriate restoration efforts undertaken. Protected areas where human extraction is limited show substantially higher biodiversity and ecosystem function compared to unprotected regions. The recovery of whale populations following international whaling moratoriums, reestablishment of peregrine falcon populations after DDT bans, and restoration of California condor populations through captive breeding demonstrate that determined conservation efforts can reverse extinctions and restore populations.

Landscape-scale restoration efforts increasingly demonstrate ecological recovery potential. Rewilding initiatives that reintroduce large predators and herbivores to degraded landscapes show that ecosystems possess substantial resilience when given opportunity for recovery. The reintroduction of bison to North American grasslands, wolves to European ecosystems, and large herbivores to African savannas all trigger cascading ecological recovery that restores ecosystem function and biodiversity. These successes suggest that even heavily degraded systems can recover if human pressures are substantially reduced.

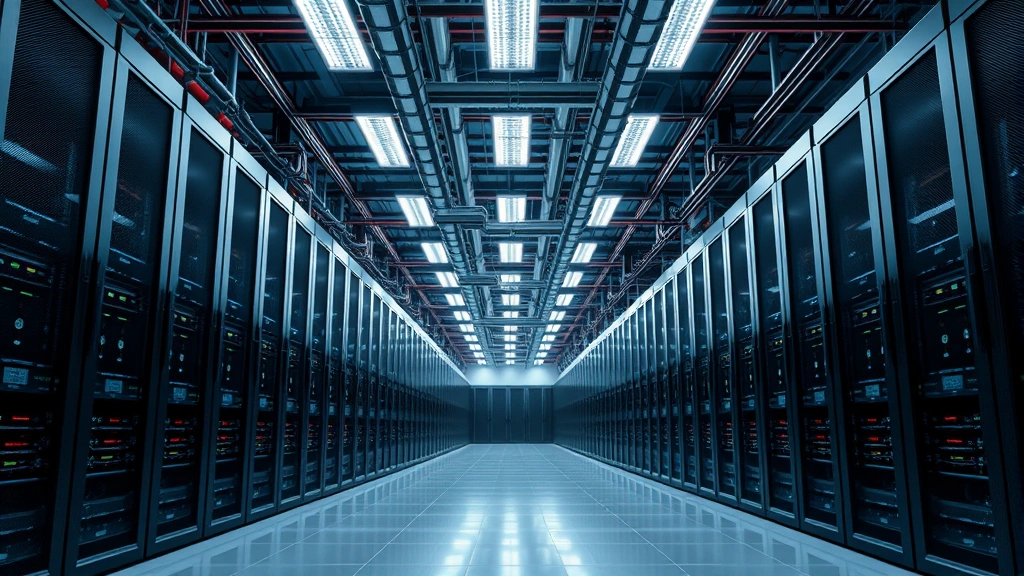

Renewable energy transitions represent essential pathways for reducing climate impacts on ecosystems. Replacing fossil fuel infrastructure with wind, solar, and other renewable sources eliminates both greenhouse gas emissions and the ecological disruptions associated with coal mining, oil extraction, and natural gas development. The declining costs of renewable technologies—now cheaper than fossil fuels in most regions—remove economic barriers to rapid transition, leaving policy and institutional inertia as primary obstacles.

Agricultural system transformation toward regenerative and agroecological approaches offers potential for simultaneous food production and ecosystem recovery. Practices including cover cropping, reduced tillage, integrated pest management, and polyculture agriculture rebuild soil health, support pollinator populations, and reduce chemical pollution while maintaining or increasing productivity. The global regenerative agriculture movement demonstrates growing recognition that industrial agriculture’s ecological costs are economically unsustainable and unnecessary.

Policy mechanisms including payment for ecosystem services, biodiversity offsets, and carbon pricing attempt to internalize environmental costs into economic decision-making. However, scientific evidence suggests these market-based mechanisms often fail to achieve conservation objectives when not coupled with regulatory protections and direct ecosystem management. The most successful conservation outcomes combine protected areas with sustainable use restrictions, restoration investments, and community engagement ensuring that conservation benefits local populations.

International cooperation through treaties including the Convention on Biological Diversity, Paris Climate Agreement, and emerging agreements on ocean protection provides frameworks for coordinated ecosystem protection. Yet implementation remains inconsistent, with wealthy nations often failing to meet commitments while pressuring developing nations to restrict resource use despite historical responsibility for ecosystem degradation. Effective global ecosystem recovery requires acknowledging these equity dimensions and ensuring that conservation costs are borne by nations responsible for the majority of ecosystem impacts.

FAQ

What is the primary driver of current species extinctions?

Habitat destruction accounts for approximately 85 percent of species extinctions, with remaining mortality from overexploitation, invasive species, pollution, and climate change. The conversion of natural ecosystems to agriculture, urban development, and resource extraction eliminates the complex habitats that species require for survival.

How do human activities affect ocean ecosystems differently than terrestrial systems?

Ocean ecosystems face distinct pressures including overfishing that removes apex predators and disrupts trophic structure, plastic pollution that fragments into microplastics pervading food webs, ocean acidification from CO2 absorption altering calcification processes, and warming that disrupts phenological synchronization. Coastal ecosystems face additional pressure from nutrient pollution creating dead zones and physical habitat destruction from development.

Can ecosystems recover from human-induced degradation?

Yes, scientific evidence demonstrates substantial recovery potential when human pressures are reduced. Protected areas, rewilding initiatives, and restoration efforts show that ecosystems possess resilience enabling recovery. However, recovery timescales depend on degradation severity—some systems require decades to centuries for full recovery while others may recover within years if stressors are removed.

How do ecosystem services relate to human economic wellbeing?

Ecosystem services including pollination, water purification, climate regulation, and soil formation underpin human economic activity. Economic valuations reveal that ecosystem service losses exceed trillions of dollars annually, yet these costs remain externalized from market prices. Recognizing ecosystem services as fundamental economic assets reveals that ecosystem preservation provides superior economic returns compared to conversion for short-term resource extraction.

What role do individual actions play in reducing human ecosystem impacts?

While individual consumption choices matter, systemic change requires policy and institutional transformation. Individual actions including reduced consumption, dietary shifts toward lower-impact foods, and support for conservation policies contribute to broader cultural shifts enabling political change. However, approximately 70 percent of global emissions derive from relatively few corporations and industries, indicating that systemic transformation requires policy intervention alongside individual behavior change.