Is Green Economy Sustainable? Expert Insights on Environmental Safety and Economic Viability

The green economy represents one of the most significant paradigm shifts in modern economics, promising to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation. However, critical questions persist about whether this transition can genuinely deliver on its sustainability promises while maintaining economic stability and environmental safety. This comprehensive analysis examines expert perspectives on green economy sustainability, exploring both the transformative potential and inherent limitations of this approach.

Environmental safety concerns have become increasingly central to economic policy discussions worldwide. As nations grapple with climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion, the green economy model offers a framework for achieving prosperity without compromising ecological integrity. Yet the evidence suggests that success depends heavily on implementation strategies, regulatory frameworks, and genuine commitment to systemic change rather than superficial greenwashing.

Defining Green Economy and Environmental Safety

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) defines the green economy as one that results in improved human well-being and social equity while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. This definition fundamentally integrates environmental science principles with economic policy, creating a framework where environmental safety becomes inseparable from economic performance.

Environmental safety, in this context, encompasses protection from pollution, resource depletion, climate disruption, and ecosystem collapse. It requires that economic activities maintain the capacity of natural systems to provide essential services—carbon sequestration, water purification, pollination, and nutrient cycling. The green economy model attempts to internalize these ecological functions into economic decision-making, moving beyond traditional frameworks that treat environmental protection as an external cost.

Experts from the World Bank and ecological economics institutions emphasize that true green economy sustainability requires measuring wealth beyond gross domestic product. This necessitates accounting for natural capital depletion, environmental damage costs, and the value of ecosystem services. The challenge lies in operationalizing these measurements across diverse economies with varying resource bases and development stages.

Core Pillars of Green Economic Transition

The green economic transition rests on several interconnected pillars. First, renewable energy deployment represents the foundation of decarbonization efforts. Solar, wind, and hydroelectric systems now compete economically with fossil fuels in many markets, fundamentally altering energy economics. However, critics note that renewable energy transition requires substantial mineral extraction for batteries and solar panels, creating new environmental pressures in regions with weak environmental governance.

Second, circular economy principles aim to minimize waste and maximize resource efficiency. By designing products for reuse, repair, and recycling, circular systems theoretically reduce extraction pressures and associated environmental damage. Yet implementing circular systems at scale requires significant infrastructure investment and behavioral change, with uncertain success rates across different sectors and geographies.

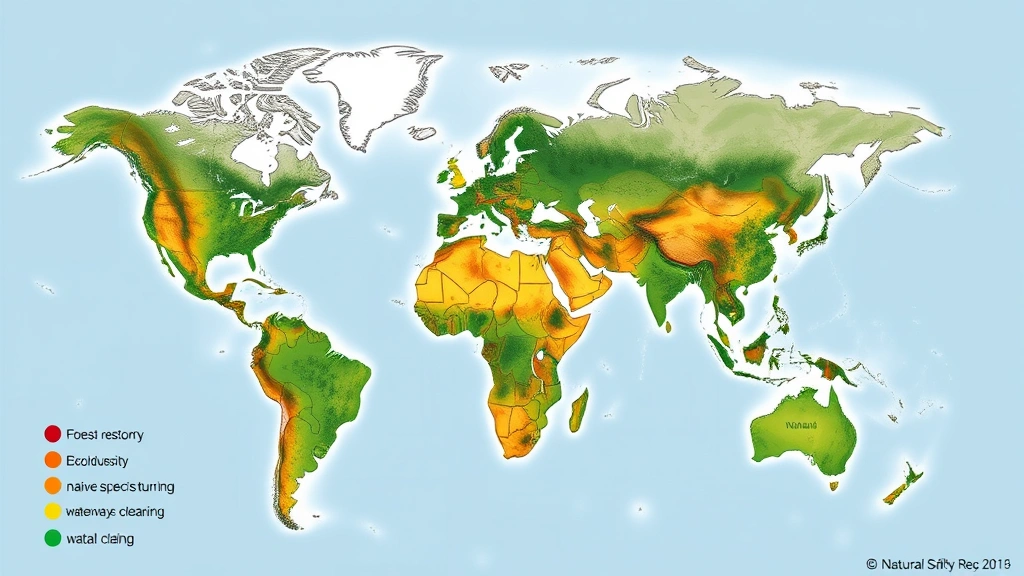

Third, ecosystem restoration and conservation represent critical safety mechanisms. Protecting forests, wetlands, and marine ecosystems preserves natural carbon sinks while maintaining biodiversity. The Environment Protection Act 2024 and similar regulatory frameworks increasingly mandate environmental impact assessments and restoration requirements, though enforcement remains inconsistent globally.

Fourth, sustainable agriculture and land management practices attempt to maintain food security while reducing agricultural environmental footprints. Regenerative agriculture, precision farming, and agroforestry approaches show promise but require farmer education, investment, and market incentives to achieve widespread adoption.

Measuring True Sustainability Outcomes

One of the most contentious aspects of green economy assessment involves measurement methodologies. Traditional economic indicators fail to capture environmental degradation adequately. The Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) and Natural Capital Accounting attempt to address these gaps by incorporating environmental costs into economic calculations.

Research from ecological economics journals reveals significant discrepancies between headline green economy claims and measurable environmental outcomes. For instance, carbon offset markets sometimes create perverse incentives, where projects claim environmental benefits that fail to materialize or generate negative unintended consequences. Similarly, renewable energy transitions in some regions have proceeded without adequate consideration of mining impacts, water usage, or land conversion effects.

Expert analysis suggests that sustainability requires monitoring multiple environmental safety indicators simultaneously: greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity indices, water quality metrics, soil health measures, and pollution levels. No single metric can adequately capture green economy performance. Furthermore, temporal considerations matter significantly—short-term economic gains that compromise long-term environmental safety represent failures by genuine sustainability standards.

Challenges and Contradictions in Green Growth

Despite optimistic projections, several fundamental challenges complicate green economy sustainability claims. The rebound effect—where efficiency improvements lead to increased consumption rather than reduced environmental impact—undermines many green initiatives. When renewable electricity becomes cheaper, overall electricity consumption often increases, partially offsetting emissions reductions.

Additionally, the focus on green growth assumes that economic expansion and environmental protection can proceed simultaneously without fundamental contradiction. Critics argue that infinite growth on a finite planet remains physically impossible, regardless of technological improvements. True sustainability may require accepting steady-state or degrowth economics in wealthy nations while supporting development in lower-income countries.

The green economy also risks perpetuating global inequalities. Wealthy nations can afford expensive renewable transitions and green technologies, while developing countries remain dependent on fossil fuels and resource extraction. Technology transfer remains inadequate, and international agreements often reflect the interests of developed economies. Understanding human environment interaction patterns reveals how economic power shapes environmental outcomes globally.

Geographic disparities in environmental impact distribution present another challenge. While wealthy countries transition to green economies, they often outsource environmentally damaging production to nations with weaker environmental protection licenses and enforcement. Carbon accounting methodologies that measure consumption-based emissions rather than production-based emissions reveal that wealthy nations’ green economy transitions may actually increase global environmental degradation.

Policy Frameworks and Regulatory Requirements

Successful green economy transitions require robust policy frameworks that create consistent incentives for environmental safety. Carbon pricing mechanisms—whether through taxes or cap-and-trade systems—attempt to incorporate climate costs into economic decisions. However, policy design matters enormously. Weak carbon prices fail to drive meaningful behavior change, while poorly designed systems create loopholes and unintended consequences.

Regulatory standards for pollution, resource extraction, and ecosystem protection provide essential guardrails. The UNEP emphasizes that environmental safety requires binding legal standards with adequate enforcement mechanisms and penalties for violations. Yet regulatory stringency varies dramatically across jurisdictions, creating incentives for regulatory arbitrage where polluting industries relocate to countries with weaker standards.

Green procurement policies, renewable energy mandates, and ecosystem protection laws provide direct policy levers. Countries implementing comprehensive policy packages—combining multiple instruments across energy, agriculture, industry, and transportation sectors—demonstrate stronger environmental outcomes than those relying on market mechanisms alone.

International agreements and trade policies increasingly incorporate environmental considerations, though tensions persist between free trade principles and environmental protection. The challenge lies in designing policies that prevent both environmental degradation and economic disruption for workers and communities dependent on transitioning industries.

Investment Trends and Market Mechanisms

Green investment has grown exponentially, with trillions of dollars flowing toward renewable energy, electric vehicles, energy efficiency, and sustainable infrastructure. This capital mobilization demonstrates genuine market recognition of green economy opportunities. However, investment distribution remains highly concentrated in wealthy nations and specific sectors, with emerging markets and crucial areas like ecosystem restoration receiving disproportionately small shares.

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing attempts to align capital allocation with sustainability goals. Yet ESG frameworks remain inconsistently defined, with greenwashing concerns legitimate. Companies can achieve high ESG ratings while maintaining environmentally damaging practices in supply chains or through carbon-intensive operations in other jurisdictions.

Public finance mechanisms—green bonds, development banks’ sustainable lending, and government subsidies—complement private investment. However, many governments simultaneously subsidize fossil fuels at rates exceeding green energy support, creating contradictory incentive structures. Genuine sustainability requires aligning all financial flows with environmental safety objectives.

Market mechanisms like carbon trading show mixed results. While theoretically efficient, practical implementation reveals problems: baseline manipulation, credit inflation, additionality questions, and insufficient price signals to drive transformative change. Some economists argue that regulatory standards and direct investment in clean infrastructure prove more effective than market-based mechanisms alone.

Expert Consensus and Future Directions

Despite disagreements about specific mechanisms, expert consensus identifies several requirements for genuine green economy sustainability. First, environmental safety must become a binding constraint rather than an optimization target. Ecosystem tipping points and planetary boundaries establish non-negotiable limits that economic activity cannot exceed.

Second, systemic change requires transforming energy systems, agricultural practices, industrial processes, and consumption patterns simultaneously. Piecemeal approaches that address climate change while ignoring biodiversity loss or pollution represent inadequate responses to interconnected environmental challenges.

Third, justice and equity considerations prove essential to sustainability. Green transitions that concentrate benefits among wealthy populations while imposing costs on vulnerable communities prove neither economically sustainable nor politically viable long-term. Genuine sustainability requires equitable distribution of transition benefits and costs.

Fourth, ecological economics research increasingly emphasizes that environmental safety requires operating within biophysical limits. Technological solutions, while important, cannot overcome fundamental physical constraints. Sustainability ultimately requires aligning economic activity with planetary boundaries and ecological regeneration capacity.

Looking forward, expert insights suggest that green economy sustainability depends less on technology availability and more on political will and institutional capacity. Most required technologies exist; implementation barriers involve economic interests, political resistance, and coordination challenges rather than technical impossibility.

FAQ

What exactly is a green economy, and how does it differ from traditional economics?

A green economy integrates environmental protection into economic decision-making, internalizing ecological costs and benefits rather than treating them as external factors. Unlike traditional economics, which prioritizes GDP growth regardless of environmental impacts, green economics explicitly targets environmental safety alongside economic prosperity. This requires measuring progress through multiple indicators including natural capital, ecosystem health, and pollution levels rather than solely through output measures.

Can renewable energy truly replace fossil fuels without environmental damage?

Renewable energy represents essential infrastructure for decarbonization, but the transition itself involves environmental costs. Mining for lithium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals creates ecological damage; solar panel production requires energy and generates waste; wind farms impact bird populations. True sustainability requires managing these trade-offs through responsible mining practices, recycling infrastructure, and strategic site selection. Complete environmental neutrality remains impossible, but renewable systems produce dramatically lower lifecycle environmental impacts than fossil fuels.

Why do some experts remain skeptical about green economy claims?

Skepticism stems from several sources: observed rebound effects where efficiency gains increase overall consumption; concerns that green growth assumptions contradict biophysical limits; evidence that wealthy nations’ green transitions sometimes increase global environmental damage through outsourced production; and recognition that greenwashing allows continued environmentally harmful practices under green labels. Genuine sustainability requires fundamental system change, not merely technological substitution.

How do policy frameworks ensure environmental safety during economic transitions?

Effective frameworks combine multiple policy instruments: binding environmental standards with enforcement mechanisms; carbon pricing that reflects true climate costs; investment in clean infrastructure; protection for workers and communities affected by transitions; and international coordination preventing regulatory arbitrage. No single policy instrument suffices; comprehensive approaches addressing energy, agriculture, industry, and consumption simultaneously prove most effective.

What role does measuring natural capital play in green economy assessment?

Natural capital accounting attempts to quantify ecosystem services—carbon sequestration, water purification, pollination, nutrient cycling—in economic terms. This enables comparison of economic benefits against environmental costs using common metrics. However, challenges persist in valuation accuracy, temporal considerations, and irreversibility thresholds. Some argue certain natural capital cannot be adequately priced, requiring regulatory protection regardless of economic calculations.

Is degrowth necessary for true sustainability?

This remains debated among experts. Some argue that technological efficiency improvements and renewable energy transitions enable continued growth with reduced environmental impact. Others contend that biophysical limits make infinite growth impossible, requiring wealthy nations to accept steady-state or reduced consumption while supporting development in lower-income countries. The answer likely varies by nation and sector, with some areas capable of green growth while others require intentional contraction.