Is Green Economy Sustainable? An Economist’s Critical Insight

The global transition toward a green economy represents one of the most significant economic restructuring efforts in modern history. Yet beneath the optimistic rhetoric of environmental sustainability and carbon neutrality lies a complex economic reality that demands rigorous scrutiny. As economists and environmental scientists examine whether green economic models can genuinely sustain both ecological and financial systems, critical questions emerge about implementation feasibility, distributional equity, and long-term viability.

A green economy, fundamentally defined as an economic system that reduces environmental risks and ecological scarcities while maintaining human well-being, promises to decouple economic growth from resource depletion and pollution. However, the tension between continuous economic expansion and planetary boundaries creates what many economists term a hostile environment for traditional growth paradigms. Understanding this contradiction requires examining the structural challenges, measurement problems, and policy mechanisms that determine whether green economy initiatives can genuinely deliver sustainable outcomes.

This analysis explores the economist’s perspective on green economy sustainability, integrating ecological economics frameworks, empirical data on decoupling claims, and critical assessments of current policy mechanisms. The investigation reveals both promising pathways and fundamental obstacles that policymakers and investors must navigate.

Defining Green Economy and Sustainability Paradoxes

The green economy concept emerged prominently during the 2008 financial crisis when economists and policymakers sought alternative development models. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) defines it as one that results in improved human well-being and social equity while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. This definition encompasses renewable energy infrastructure, sustainable agriculture, ecosystem restoration, and circular production systems.

However, this framework contains inherent contradictions. Mainstream green economy discourse maintains that economic growth can continue indefinitely through technological innovation and efficiency improvements. This position conflicts with biophysical reality: Earth operates within finite resource boundaries and ecological regeneration limits. Economists working within UNEP’s analytical frameworks increasingly acknowledge that current green economy models may represent greening of capitalism rather than fundamental systemic transformation.

The hostile environment facing traditional economics stems from recognizing that natural capital—forests, fisheries, mineral deposits, atmospheric composition—functions as both productive input and waste sink. When economic activity degrades these assets faster than regeneration occurs, economists describe this as unsustainable extraction. A genuine green economy must operate within regeneration rates, creating what ecological economists call a steady-state economy rather than continuous expansion.

Consider the relationship between economic activity and human environment interaction. Traditional models treat environmental degradation as externality—a cost borne by society rather than reflected in market prices. Green economy approaches attempt internalizing these costs through carbon pricing, ecosystem service valuation, and natural capital accounting. Yet measurement remains contentious, with significant disagreements about shadow prices for ecosystem services.

The Decoupling Debate: Economic Growth Versus Environmental Impact

Central to green economy sustainability claims is the concept of decoupling—achieving economic growth while reducing material throughput and environmental impact. Proponents argue that wealthy nations demonstrate relative decoupling, where GDP grows while resource consumption and emissions decline. Germany’s Energiewende and Costa Rica’s renewable energy expansion exemplify this narrative.

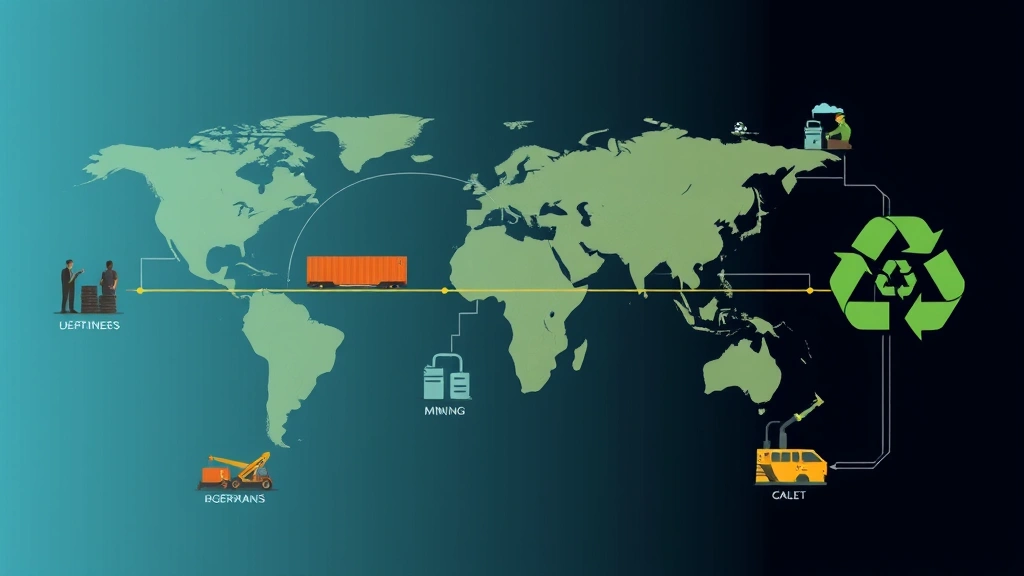

However, critical economists identify significant methodological problems with decoupling claims. Absolute decoupling—where total environmental impact genuinely declines—remains elusive globally. Most apparent decoupling reflects carbon leakage, where wealthy nations outsource manufacturing to developing countries with looser environmental standards. When accounting for consumption-based emissions—including embodied carbon in imported goods—decoupling largely disappears.

Research from ecological economics journals demonstrates that relative decoupling often masks structural shifts rather than genuine sustainability improvements. When manufacturing moves from Germany to Vietnam, German carbon accounts improve while global emissions increase due to less efficient production methods and transportation distances. The World Bank’s sustainable development data reveals that material extraction globally continues accelerating despite green economy investments in wealthy nations.

Furthermore, technological efficiency gains frequently trigger rebound effects. When renewable energy reduces electricity costs, increased consumption may offset efficiency improvements. This Jevons paradox—where efficiency increases lead to greater resource consumption—suggests that technological solutions alone cannot achieve sustainability within growth-oriented frameworks. Economists debate whether policy interventions can overcome rebound effects or whether fundamental consumption patterns require transformation.

Measurement Challenges and Hidden Environmental Costs

Assessing green economy sustainability demands sophisticated environmental accounting. Traditional GDP measurements exclude environmental degradation, creating perverse incentives where resource depletion appears as income rather than capital loss. Green GDP attempts correcting this by subtracting environmental costs from economic output.

Valuing environmental services presents formidable challenges. What price should ecosystem services command? Wetland water filtration, pollination services, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity maintenance resist monetary quantification. Different valuation methodologies produce vastly different results. Contingent valuation surveys asking willingness-to-pay differ substantially from revealed preference methods analyzing actual market transactions.

The hostile environment for accurate measurement extends to supply chain complexity. A smartphone’s true environmental cost includes rare earth mining in China, manufacturing emissions in Taiwan, transportation energy, and eventual e-waste recycling challenges. Attributing these costs across supply chains requires data transparency that corporations frequently resist. Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies produce different results depending on system boundaries and allocation methodologies.

Additionally, temporal dimensions complicate sustainability assessment. Some environmental damages—climate tipping points, biodiversity extinction, soil degradation—manifest over decades or centuries. Economists using present value calculations may severely undervalue future environmental impacts, creating systematic bias toward present consumption. Intergenerational equity demands higher discount rates for environmental damages, yet this conflicts with standard financial analysis.

When examining how to reduce carbon footprint at individual and organizational levels, measurement ambiguities become apparent. Scope 1, 2, and 3 emission categories create opportunities for selective accounting. Companies may emphasize operational emissions reductions while ignoring supply chain and product-use phase impacts.

Policy Mechanisms and Market-Based Solutions

Green economy policy relies heavily on market mechanisms: carbon pricing, cap-and-trade systems, payment for ecosystem services, and green bonds. These approaches assume that internalizing environmental costs through price signals will trigger sustainable behavior shifts. The European Union’s Emissions Trading System represents the largest carbon market, while numerous countries implement carbon taxes.

However, market-based mechanisms face structural limitations. Carbon pricing levels remain insufficient to reflect true environmental costs. Most carbon prices globally hover below $50 per ton, while climate economists estimate true social cost of carbon exceeds $100 per ton. This underpricing means markets fail to incentivize necessary behavioral changes.

Additionally, cap-and-trade systems create perverse outcomes. Allowance allocation, banking provisions, and offset mechanisms enable continued emissions from wealthy entities through permit purchases. Critics argue this approach privileges polluters while imposing costs on developing nations expected to reduce emissions faster than wealthy countries. The concept of environmental justice becomes central: who bears transition costs?

Payment for ecosystem services schemes demonstrate similar challenges. When governments pay landowners for forest conservation, additionality becomes questionable—would deforestation have occurred anyway? Transaction costs consume significant portions of payments. Market prices for environmental services fail to reflect ecological importance, creating incentives to protect economically valuable ecosystems while neglecting others.

Regulatory approaches—emission standards, renewable energy mandates, efficiency requirements—complement market mechanisms. The renewable energy transition for homes accelerates through policy mandates requiring grid operators to source increasing percentages from renewables. These regulations overcome market failures where environmental benefits aren’t captured through prices.

Sectoral Transitions: Renewable Energy and Circular Economy

Renewable energy expansion represents green economy’s most visible achievement. Solar and wind capacity additions outpace fossil fuel growth in many regions. Costs have declined dramatically—utility-scale solar costs fell 90% since 2010. This technological progress suggests green economy pathways becoming economically competitive.

Yet renewable transition complexity extends beyond cost comparisons. Intermittency challenges require energy storage, grid modernization, and demand management infrastructure—additional costs not always captured in renewable cost analyses. Mining requirements for battery materials (lithium, cobalt, nickel) create new environmental pressures and labor concerns in developing nations. When accounting for full lifecycle impacts, renewable energy superiority becomes less pronounced than marketing narratives suggest.

The circular economy concept—designing out waste through product redesign, reuse, and recycling—offers alternative sustainability pathway. Rather than linear take-make-dispose models, circular approaches maintain material value through multiple use cycles. Companies implementing circular design report reduced material costs and improved brand value.

However, circular economy faces thermodynamic constraints. Each recycling cycle degrades material quality, requiring virgin material supplementation. Energy-intensive recycling processes may offset environmental benefits. Economic viability depends on material values and labor costs—recycling remains economically marginal for many materials without subsidies. The hostile environment for circularity includes regulatory frameworks designed for linear production and consumer preferences for new products.

Distributional Justice and Equity Concerns

Green economy sustainability requires addressing distributional dimensions. Transition costs concentrate among workers in fossil fuel industries, communities dependent on resource extraction, and developing nations facing pressure to abandon development pathways wealthy countries utilized. Energy transitions threaten coal miners’ livelihoods without guaranteed alternative employment.

Climate finance mechanisms promise supporting developing nation transitions, yet actual flows fall short of commitments. The promised $100 billion annual climate finance for developing countries remains unmet, with much funding structured as loans rather than grants. This creates debt burdens while wealthy nations maintain consumption patterns.

Green technology deployment exhibits troubling equity patterns. Renewable energy benefits concentrate among wealthy households installing rooftop solar. Electric vehicles remain luxury goods inaccessible to low-income populations. As sustainable fashion brands market premium products, access disparities grow. Environmental benefits become luxury amenities rather than universal improvements.

The concept of environmental colonialism describes how wealthy nations externalize green economy costs to developing countries. Biofuel mandates drive agricultural land conversion in Africa and Asia, displacing smallholders. Mining for renewable energy materials concentrates in Global South with minimal benefit-sharing. Wealthy nations achieve emissions reductions by outsourcing production while maintaining consumption levels.

Genuine sustainability requires just transitions ensuring affected workers and communities share transition benefits. This demands income redistribution, skills training, healthcare continuity, and community investment—politically challenging in societies prioritizing growth. The hostile environment for equity stems from economic structures rewarding capital concentration while marginalizing labor and communities.

Future Pathways: Can Green Economy Deliver Sustainability?

Assessing whether green economy can deliver sustainability requires distinguishing between optimistic scenarios and probable outcomes. Technological potential exists—renewable energy, energy efficiency, and circular production could support human well-being within planetary boundaries. However, realizing this potential demands systemic changes that current political economy resists.

Three potential pathways emerge from economic analysis. First, green growth maintains current systems while substituting clean technologies. This approach preserves economic structures, corporate power, and consumption patterns while reducing environmental intensity. It offers least disruption but risks failing to achieve necessary emissions reductions given historical decoupling limitations.

Second, steady-state economy models decouple well-being from material throughput through reduced consumption in wealthy nations, redistributive policies, and sufficiency-oriented lifestyles. This pathway acknowledges biophysical boundaries and prioritizes equity but requires fundamental economic restructuring and consumption pattern shifts that political systems struggle implementing.

Third, degrowth approaches explicitly reject growth as sustainability objective, advocating planned economic contraction in wealthy nations to create ecological space for development in poor regions. While ecologically rational, degrowth faces severe political obstacles and distributional challenges without accompanying institutional transformation.

Current policy trajectories blend elements from all three, creating incoherent frameworks. Nations simultaneously pursue growth targets while implementing emissions reductions, creating contradictions that weaken both objectives. The hostile environment for genuine sustainability stems from this fundamental tension: continuing growth-oriented systems while addressing ecological limits represents a square circle.

Economists increasingly recognize that sustainability questions aren’t primarily technical but political. Renewable energy feasibility, circular economy potential, and just transition mechanisms all exist technically. Implementation requires political will to challenge incumbent interests, redistribute resources, and transform economic institutions. Whether democratic societies can mobilize this capacity remains the critical uncertainty.

The green economy’s sustainability ultimately depends on whether it represents genuine transformation or strategic accommodation of capitalism to environmental constraints. If green economy becomes vehicle for capital accumulation in new sectors while maintaining core growth imperatives and inequality structures, sustainability remains illusory. If it catalyzes fundamental institutional changes, equity improvements, and consumption reductions in wealthy nations, genuine sustainability becomes possible.

FAQ

What distinguishes green economy from sustainable economy?

Green economy typically emphasizes technological substitution and market mechanisms for environmental integration within growth frameworks. Sustainable economy more broadly encompasses ecological limits recognition, intergenerational equity, and potentially non-growth pathways. Green economy represents narrower concept, while sustainable economy demands deeper systemic transformation.

Can renewable energy fully replace fossil fuels?

Technically feasible, yes—renewable resources exceed human energy needs. However, transition requires storage infrastructure, grid modernization, material sourcing for batteries and panels, and behavioral changes around consumption. Economic viability depends on carbon pricing levels, technological costs, and political support. Most analyses suggest 80-90% renewable electricity possible by 2050 with current technology, while complete decarbonization demands additional solutions for aviation, shipping, and high-temperature industrial heat.

Why do carbon markets fail achieving emissions reductions?

Carbon prices remain below social cost of carbon, insufficient to trigger necessary behavioral changes. Allowance allocation favors incumbent polluters. Offset mechanisms enable continued emissions without genuine reductions elsewhere. Regulatory approaches combined with carbon pricing prove more effective than markets alone, though political resistance to regulation limits implementation.

How do developing nations navigate green economy transitions?

Developing nations face acute tensions: growth necessary for poverty reduction versus emissions reduction requirements. Green finance mechanisms provide inadequate support. Technology transfer remains limited by intellectual property protections. Just transition requires wealthy nation support including debt relief, technology access, and climate finance—currently insufficient. Many developing nations pursue green growth while maintaining fossil fuel expansion, reflecting realistic assessment of available resources.

What does ecological economics offer beyond mainstream environmental economics?

Ecological economics explicitly incorporates biophysical boundaries, thermodynamic constraints, and recognition that economy remains embedded within finite ecosystems. It challenges growth assumptions, emphasizes scale limits, and prioritizes distributional equity. Mainstream environmental economics typically treats environmental protection as policy add-on to growth frameworks, while ecological economics demands fundamental system redesign acknowledging ecological constraints as primary constraint on economic activity.