Impact of Economy on Ecosystems: A Deep Dive

The global economy and natural ecosystems exist in an intricate dance of mutual dependence and conflicting pressures. As economic systems expand and intensify their resource extraction, manufacturing, and consumption patterns, ecosystems worldwide face unprecedented stress. This interconnection between economic activity and ecological health represents one of the most critical challenges of our time, requiring a fundamental reassessment of how we measure progress, allocate resources, and structure the operational framework in which businesses and communities function.

For decades, conventional economic models treated nature as an infinite resource—a commons available for unlimited exploitation. However, mounting evidence from environmental science, ecological economics, and conservation biology reveals that this assumption is fundamentally flawed. Every economic transaction carries ecological costs that traditional accounting systems fail to capture. From the carbon emissions of manufacturing supply chains to the biodiversity loss from agricultural expansion, the true price of economic growth remains largely invisible in standard financial reports. Understanding these connections requires examining how specific economic sectors impact ecosystems, how market failures perpetuate environmental degradation, and what alternatives might create a more sustainable balance between human prosperity and ecological integrity.

How Economic Growth Degrades Natural Systems

Economic growth, measured primarily through Gross Domestic Product (GDP), has become the dominant metric for national success and societal wellbeing. Yet this pursuit of perpetual expansion directly contradicts the biophysical reality of living on a finite planet. As economies grow, they typically require increased extraction of raw materials, more energy consumption, and greater waste generation—each of which places stress on ecosystems.

The mechanism is straightforward: industrial economies depend on converting natural capital into economic value. Forests become timber and agricultural land. Minerals are extracted from mountains. Fossil fuels are burned for energy. Fish stocks are harvested from oceans. In each case, the economic system captures the immediate value while externalizing the ecological costs. Soil degradation, water pollution, air quality decline, and species extinction are treated as inevitable byproducts rather than fundamental accounting failures.

Research from the World Bank demonstrates that countries with the highest GDP per capita also tend to have the largest ecological footprints. A single American citizen consumes resources at a rate requiring approximately 5 Earth equivalents if replicated globally. This disparity reveals that current economic structures fundamentally depend on ecological inequity—wealthy nations maintain high consumption levels by externalizing environmental costs to developing regions and future generations.

The decoupling hypothesis—the notion that economic growth can be separated from resource consumption and environmental degradation—has become increasingly central to policy discussions. Yet evidence suggests that relative decoupling (reducing environmental impact per unit of GDP) remains modest and insufficient, while absolute decoupling (reducing total environmental impact despite economic growth) remains elusive at the global scale. When accounting for supply chain outsourcing and imported goods, many developed nations have merely shifted their environmental impacts rather than eliminated them.

Key Economic Sectors and Their Ecological Footprints

Different economic sectors impose vastly different ecological burdens. Understanding these sector-specific impacts is essential for targeted policy intervention and corporate accountability. Agriculture represents perhaps the most transformative economic activity, occupying approximately 40% of global land surface and driving massive habitat conversion, freshwater depletion, and chemical pollution.

Agricultural intensification has enabled food production for billions, yet comes at tremendous ecological cost. Industrial monocultures require heavy pesticide and fertilizer inputs, contaminating waterways and reducing soil health. Livestock production—particularly beef and dairy—drives deforestation in tropical regions, generates substantial methane emissions, and consumes disproportionate water and feed resources. The expansion of palm oil plantations in Southeast Asia exemplifies how commodity-driven economics directly conflicts with biodiversity conservation, as pristine rainforests are converted to productive plantations.

The energy sector, dominated by fossil fuel extraction and combustion, represents the largest driver of climate change while also generating localized ecological damage through mining, refining, and transportation. Extractive industries—mining for metals, coal, and minerals—create permanent landscape scars, contaminate groundwater, and displace indigenous communities. Even renewable energy infrastructure, while necessary for climate mitigation, requires careful environmental assessment to minimize habitat disruption.

Manufacturing and industrial production generate pollution across multiple pathways: air emissions from factories, water contamination from discharge and runoff, and persistent accumulation of toxic substances in ecosystems. The fashion industry, despite its image as non-extractive, consumes vast quantities of water, generates textile waste, and relies on chemical-intensive production processes. Sustainable fashion brands represent emerging alternatives, though they remain marginal within the broader industry structure.

Transportation networks—roads, railways, shipping lanes, and airports—fragment ecosystems, alter hydrological systems, and contribute substantially to greenhouse gas emissions. The global supply chain infrastructure that enables contemporary consumer economies requires continuous resource inputs and generates emissions throughout production and distribution networks.

Financial systems and real estate development drive land-use conversion through speculation, infrastructure development, and urban sprawl. The human environment interaction increasingly occurs through economically-driven urbanization patterns that privilege development over conservation.

Market Failures and Externalities in Environmental Economics

At the theoretical heart of economic-ecological conflict lies a fundamental market failure: the failure to price environmental goods and services. Economists recognize this as the externality problem—costs or benefits of economic activities that are not reflected in market prices.

When a factory pollutes a river, the cost of cleanup, lost fisheries, and human health impacts are not deducted from the company’s profits. When deforestation occurs, the loss of carbon sequestration capacity, biodiversity habitat, and watershed services are not reflected in the timber company’s revenue. When fossil fuels are burned, the costs of climate change—increasingly severe weather, agricultural disruption, infrastructure damage—are socialized across society while profits remain privatized.

This asymmetry creates perverse economic incentives. From a purely financial perspective, it is rational for firms to externalize costs whenever possible. Pollution becomes economically efficient. Biodiversity destruction becomes profitable. Resource depletion becomes growth. The market, far from being a neutral mechanism for allocating scarce resources, systematically undervalues nature and overvalues extraction.

Environmental economists have proposed various solutions: carbon pricing mechanisms, payment for ecosystem services, natural capital accounting, and regulatory approaches. Yet implementation remains limited and inconsistent. Carbon pricing, where attempted, typically sets prices far below the actual social cost of emissions. Payments for ecosystem services often fail to compensate communities adequately for foregone development opportunities. Natural capital accounting, while conceptually sound, remains peripheral to mainstream economic policymaking.

The tragedy of the commons—where shared resources become overexploited because individual actors lack incentives for conservation—applies to countless ecosystems: fisheries collapse from overharvesting, groundwater becomes depleted from excessive extraction, and the atmosphere accumulates greenhouse gases from unrestricted emissions. Without property rights or regulatory constraints, rational economic actors systematically deplete shared resources.

The Operational Workplace and Sustainability Integration

The physical workplace environment where economic activity occurs represents both a microcosm of broader economic-ecological conflicts and a potential site for systemic change. Organizations are increasingly recognizing that their operational workplace sustainability directly impacts both ecological outcomes and long-term economic viability.

Corporate facilities consume energy, water, and materials while generating waste and emissions. The reduction of carbon footprints across organizational operations has become both an environmental imperative and a cost-reduction opportunity. Energy-efficient building systems, renewable energy installation, waste reduction programs, and sustainable procurement practices represent tangible mechanisms through which businesses can align operational practices with ecological constraints.

However, greening the workplace remains insufficient without addressing broader economic structures. An organization might achieve carbon neutrality in its operations while its supply chain generates massive emissions elsewhere. A company might install solar panels while its business model depends on promoting consumption patterns incompatible with planetary boundaries. Workplace sustainability initiatives, valuable as they are, often function as performative measures that create the appearance of environmental commitment without fundamentally altering the economic logic driving ecological degradation.

The most promising workplace sustainability approaches recognize that operational environmental performance must be paired with business model transformation. This means transitioning toward renewable energy not merely in facilities but throughout supply chains, designing products for longevity and recyclability rather than planned obsolescence, and reconsidering growth targets in light of ecological limits. It requires examining whether the organization’s core products and services are compatible with ecological sustainability or whether fundamental strategic reorientation is necessary.

Biodiversity Loss and Economic Consequences

Biodiversity—the variety of life at genetic, species, and ecosystem levels—provides essential services that underpin economic activity: pollination of crops, water purification, climate regulation, nutrient cycling, and genetic resources for medicine and agriculture. Yet current economic systems treat biodiversity as a luxury rather than a prerequisite for economic survival.

Current extinction rates are estimated at 100 to 1,000 times background rates, driven primarily by habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and overexploitation—all economically motivated. We are witnessing the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history, with the primary driver being human economic activity rather than geological catastrophe.

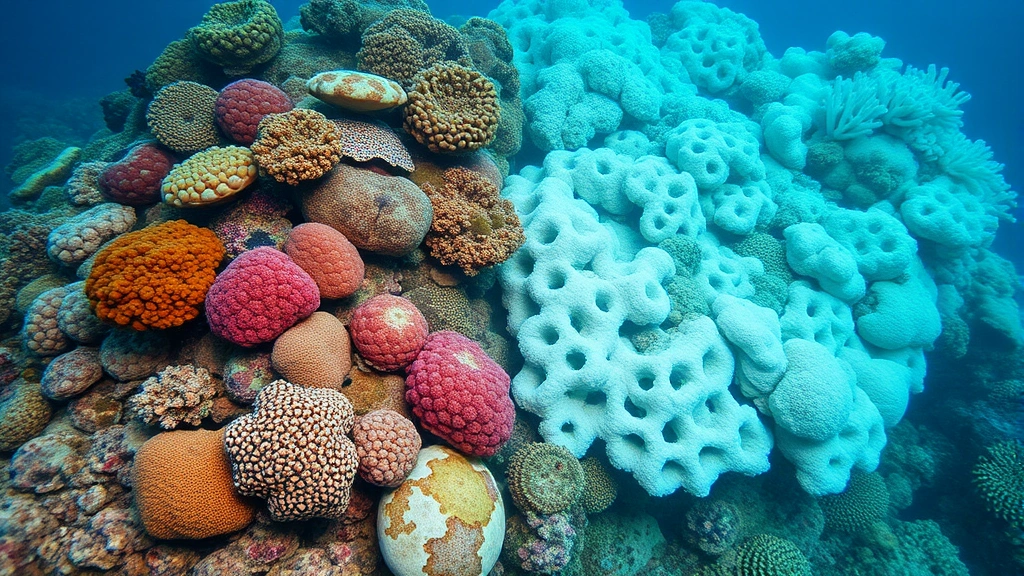

The economic consequences of biodiversity loss compound over time. Pollinator decline threatens agricultural productivity. Fisheries collapse from overharvesting. Deforestation reduces water availability. Soil degradation reduces agricultural yields. Coral bleaching undermines both fisheries and tourism economies. Yet these costs are rarely attributed to the economic activities that caused them.

Ecologists emphasize that biodiversity loss is not merely an aesthetic or moral concern but a practical threat to economic systems. Complex ecosystems exhibit greater resilience to disturbance. Simplified, monoculture-dominated systems are more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate variability. The economic logic of simplification for short-term productivity gain creates long-term vulnerability and fragility.

Indigenous territories, which cover approximately 25% of global land area, contain roughly 80% of remaining biodiversity. This correlation is not coincidental: indigenous land management practices, developed over millennia, maintain ecological complexity while supporting human communities. Yet economic development pressures consistently threaten these territories, treating indigenous stewardship as an inefficient use of valuable land.

Climate Change as an Economic-Ecological Crisis

Climate change represents the ultimate expression of economic-ecological conflict: a global commons tragedy where the atmosphere becomes a waste repository for industrial emissions, with costs distributed across all inhabitants while benefits accrue to fossil fuel producers and energy-intensive industries.

The greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change are direct byproducts of economic activity: energy production, transportation, manufacturing, agriculture, and waste. For over a century, economies have treated atmospheric carbon absorption as a free service. Only recently have policies begun attempting to price this service, yet carbon prices remain far below the actual costs of climate impacts.

Climate change creates feedback loops that threaten economic stability: agricultural disruption reduces food security and increases prices; extreme weather damages infrastructure and increases insurance costs; sea-level rise threatens coastal economies; resource scarcity drives conflict. Yet these costs are externalized from the economic actors responsible for emissions, creating continued incentives for emission-generating activities.

The transition to renewable energy, while essential, illustrates the complexity of economic-ecological transformation. Renewable energy infrastructure requires mineral extraction, manufacturing, and land use. Yet the total lifecycle emissions and ecological impacts of renewable energy systems remain substantially lower than fossil fuels. The question is not whether renewable energy is perfectly clean—it is not—but whether it represents a necessary transition toward systems compatible with planetary boundaries.

Pathways Toward Ecological Economic Reform

Addressing the fundamental conflict between unlimited economic growth and finite planetary systems requires systemic economic transformation rather than marginal improvements. Several frameworks offer potential directions.

Ecological economics represents a fundamental departure from mainstream economic thinking. Rather than treating nature as an input to economic production, ecological economics recognizes the economy as embedded within and dependent upon ecosystems. This perspective emphasizes biophysical limits, distribution equity, and long-term sustainability rather than aggregate growth.

The concept of planetary boundaries identifies critical thresholds in nine Earth systems—climate change, biosphere integrity, land-system change, freshwater use, ocean acidification, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, chemical pollution, ozone depletion, and aerosol loading—beyond which human activities risk triggering irreversible ecological changes. Economic policy should operate within these boundaries rather than treating them as externalities.

Circular economy approaches aim to minimize waste and resource extraction by designing products and systems for reuse, repair, and recycling. Rather than the linear take-make-dispose model, circular systems attempt to keep materials and nutrients in use. However, true circularity remains limited by thermodynamic constraints; some energy and materials are inevitably lost, and perfect recycling is physically impossible.

Environmental awareness and education play crucial roles in supporting systemic change. As citizens, workers, and consumers understand the ecological consequences of economic choices, political demand for policy transformation increases. Contemporary environmental discourse increasingly emphasizes the inseparability of ecological and economic justice.

Policy instruments for ecological economic reform include carbon pricing, pollution taxes, subsidy reform (removing subsidies for fossil fuels and resource extraction), protected area expansion, indigenous land rights recognition, and regulation of extractive industries. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) provides frameworks for international environmental governance, though implementation faces persistent political obstacles.

Alternative economic models emphasize sufficiency rather than growth, equity rather than efficiency, and regeneration rather than extraction. Degrowth frameworks argue that wealthy economies must deliberately reduce material and energy throughput while improving quality of life through non-material means: community, health, education, leisure, and environmental restoration. Regenerative economy approaches aim not merely to minimize harm but to actively restore and enhance ecosystem health through economic activity.

Corporate accountability mechanisms attempt to internalize environmental costs: mandatory environmental impact assessments, extended producer responsibility for products throughout their lifecycle, supply chain transparency requirements, and corporate liability for environmental damage. Yet corporate influence over regulatory processes often weakens these mechanisms substantially.

Transformation toward ecological economic systems requires coordination across multiple scales: individual consumption choices matter but remain insufficient without systemic change; national policy reform is essential but constrained by global economic competition; international agreements are necessary but face enforcement challenges. The most promising approaches combine individual action, community organization, corporate accountability, and government policy reform.

Research from leading environmental science journals increasingly emphasizes that incremental improvements to existing economic systems are incompatible with ecological stability. The scale and pace of required change suggest that fundamental economic transformation—in how we measure success, allocate resources, and structure production—is necessary rather than optional.

FAQ

How does GDP growth relate to environmental degradation?

GDP measures economic activity but not ecological health or human wellbeing. Higher GDP often correlates with greater resource extraction, pollution, and emissions. While relative decoupling (reducing environmental impact per unit of GDP) is possible, absolute decoupling at global scale remains elusive, meaning total environmental impacts continue increasing despite efficiency improvements.

Can capitalism be made environmentally sustainable?

This question divides environmental economists. Some argue that market mechanisms, properly designed with accurate environmental pricing, can align profit incentives with sustainability. Others contend that capitalism’s structural dependence on growth and accumulation is fundamentally incompatible with planetary boundaries, requiring alternative economic systems.

What role do consumers play in ecological economic transformation?

Individual consumer choices matter but are insufficient alone. While sustainable consumption reduces personal environmental impact, systemic change requires policy reform, corporate accountability, and economic restructuring. Consumer pressure can drive corporate change, but without structural incentives for sustainability, individual choices operate against powerful economic pressures toward unsustainability.

How can developing nations balance economic growth with environmental protection?

This represents a genuine equity challenge: wealthy nations industrialized without environmental constraints, while developing nations face pressure to adopt sustainable practices that limit growth. Solutions include technology transfer, differentiated climate responsibilities, fair trade mechanisms, and recognition that development should prioritize human wellbeing rather than GDP growth.

What are the economic benefits of environmental protection?

Ecosystem services—pollination, water purification, climate regulation, nutrient cycling—provide enormous economic value. Prevention of environmental damage costs far less than remediation. Renewable energy increasingly offers lower-cost energy than fossil fuels. Sustainable agriculture can maintain productivity while improving soil health. Biodiversity conservation protects agricultural and pharmaceutical resources. Yet these benefits are often invisible in standard economic accounting.