Impact of Economy on Ecosystems: A Scientific View

The relationship between economic systems and ecological health represents one of the most critical challenges facing contemporary civilization. Economic activities—from industrial manufacturing to agricultural expansion—generate cascading effects throughout natural systems, fundamentally altering biogeochemical cycles, species populations, and ecosystem services that sustain human life. Understanding this complex interplay requires an interdisciplinary approach that integrates ecological science, economics, and systems thinking to reveal how market mechanisms, production patterns, and consumption behaviors reshape planetary boundaries.

The scientific evidence is unambiguous: human economic expansion has triggered unprecedented ecological disruption. Global biodiversity loss, climate destabilization, ocean acidification, and soil degradation represent measurable outcomes of economic processes operating without adequate ecological constraints. Yet this relationship is not unidirectional. Ecosystem collapse threatens economic stability through supply chain disruptions, resource scarcity, and the erosion of natural capital that underpins all economic activity. This article examines the mechanisms through which economic systems impact ecosystems, explores quantifiable ecological consequences, and investigates pathways toward sustainable economic-ecological integration.

Economic Growth and Ecological Boundaries

Contemporary economic systems operate on assumptions of infinite growth within a finite biophysical system—a fundamental contradiction that ecological economics seeks to address. The conventional measure of economic success, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), captures monetary transactions without accounting for ecological depletion or natural capital consumption. A nation can simultaneously experience GDP growth while depleting fisheries, degrading soils, and reducing forest cover, creating an illusion of prosperity that masks ecological decline.

Research from the World Bank demonstrates that when adjusted for natural capital depreciation, economic growth rates in resource-dependent nations appear substantially lower than conventional metrics suggest. This discrepancy reveals how traditional economic accounting systems systematically undervalue ecosystem services. The biophysical limits to economic expansion operate at multiple scales: carbon absorption capacity of the atmosphere, regeneration rates of renewable resources, and assimilative capacity of ecosystems for waste products. Exceeding these boundaries generates irreversible ecological damage that manifests as climate change, resource scarcity, and ecosystem collapse.

The concept of planetary boundaries, developed by Johan Rockström and colleagues, identifies nine critical Earth system processes where economic activity has transgressed safe operating spaces. These include climate change, biodiversity loss, land-system change, freshwater depletion, and nitrogen-phosphorus cycle disruption. Economic systems driving these transgressions include fossil fuel extraction and combustion, industrial agriculture, deforestation for commodity production, and synthetic chemical manufacturing. Understanding economic-ecological relationships requires moving beyond growth-centric paradigms toward regenerative and circular economic models that respect biophysical constraints.

Mechanisms of Economic Impact on Ecosystems

Economic activities impact ecosystems through multiple pathways, operating across temporal and spatial scales. Land conversion represents the most visible mechanism: agricultural expansion, urban development, and infrastructure construction directly eliminate natural habitats, fragmenting ecosystems and isolating wildlife populations. Approximately 68% of global land-use change involves conversion of natural ecosystems to agricultural production, primarily for livestock grazing and commodity crop cultivation. This transformation reduces biodiversity, alters hydrological cycles, and degrades soil carbon stocks accumulated over millennia.

Pollution pathways constitute another critical mechanism through which economic activity degrades ecosystems. Industrial manufacturing, energy production, and transportation generate atmospheric emissions, water contaminants, and persistent organic pollutants that disperse globally. Plastic production—a petrochemical industry generating over 360 million tons annually—introduces persistent synthetic polymers into marine and terrestrial ecosystems where they persist for centuries, fragmenting into microplastics that infiltrate food webs and accumulate in organisms. Agricultural chemical inputs including pesticides and synthetic fertilizers contaminate groundwater, create hypoxic zones in coastal waters, and disrupt endocrine systems in wildlife populations.

Resource extraction economies directly deplete natural stocks faster than regeneration rates permit. Fisheries harvesting exceeds sustainable yield thresholds in 35% of global fish stocks, collapsing population structures and disrupting marine food webs. Groundwater extraction for irrigation and industrial use depletes aquifers that accumulated over thousands of years, with replenishment timescales measured in centuries or longer. Timber harvesting in tropical forests removes structural complexity and reduces carbon storage capacity, transforming carbon sinks into carbon sources. These extraction mechanisms prioritize short-term economic returns over long-term resource availability, creating trajectory shifts toward ecosystem states with reduced productive capacity.

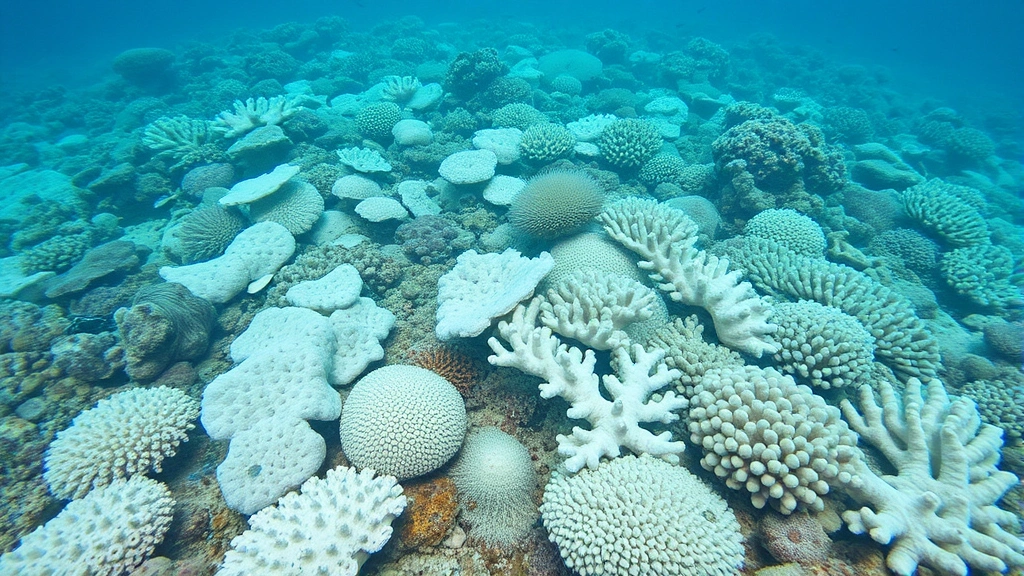

Climate forcing represents the most pervasive mechanism through which economic systems alter ecosystems. Greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion, land-use change, and industrial processes accumulate in the atmosphere, creating radiative forcing that alters global energy balance. This mechanism operates distinctly from other economic impacts because atmospheric mixing homogenizes climate forcing globally, making it a truly planetary-scale phenomenon. Rising temperatures trigger cascading ecological changes: altered precipitation patterns, extended growing seasons in some regions and drought intensification in others, coral bleaching from ocean warming, and species range shifts that disrupt coevolved ecological relationships. The rate of climate change—approximately 0.18°C per decade—exceeds the adaptive capacity of many species, generating extinction risk for temperature-sensitive organisms.

Quantifying Ecological Degradation

Scientific monitoring networks provide quantitative evidence of economic-driven ecological decline across multiple indicators. The Living Planet Index, tracking vertebrate population abundance across 32,000 populations globally, documents a 69% decline since 1970—precisely the period of accelerating globalized economic expansion. This metric reflects ecosystem degradation across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine biomes, indicating systemic failure of economic systems to maintain biological productivity.

Biodiversity loss manifests through multiple measurement approaches. Species extinction rates currently exceed background rates by 100-1,000 fold, with habitat destruction driving 70% of extinctions. Insect biomass declines of 75% in protected areas over three decades indicate that even conservation-designated lands cannot buffer against landscape-scale economic pressures. Plant diversity loss in agricultural regions reflects monoculture cultivation replacing polyculture systems that historically maintained genetic and functional diversity. These quantitative indicators translate ecological abstraction into concrete evidence that economic systems are fundamentally reorganizing planetary biology.

Carbon cycle disruption quantifies the climate forcing mechanism. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased from 280 ppm in pre-industrial times to 420 ppm currently, driven entirely by anthropogenic emissions from fossil fuel combustion and land-use change. This concentration increase corresponds to approximately 1.1°C of warming already realized, with committed warming from atmospheric CO2 persistence suggesting 1.5-2°C warming is unavoidable even with immediate emission cessation. Ocean acidification—a direct consequence of CO2 absorption—has decreased ocean pH by 0.1 units (30% increase in acidity), impairing calcification processes in pteropods, corals, and shellfish that form the foundation of marine food webs.

Nutrient cycle disruption provides another quantitative indicator of economic impact. Human activities now fix more nitrogen synthetically than all natural terrestrial processes combined, creating nitrogen saturation in many ecosystems. This excess nitrogen fertilizes primary productivity unsustainably, generating eutrophication that depletes oxygen in water bodies and creates anoxic dead zones. The Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone, driven by agricultural runoff from the Mississippi River basin, encompasses areas exceeding 20,000 square kilometers where oxygen depletion prevents most aerobic life. Similar patterns replicate globally in coastal zones adjacent to agricultural heartlands, quantifying how economic production systems disrupt fundamental biogeochemical processes.

Natural Capital Depletion

Economic systems operate by converting natural capital—the stock of environmental assets including forests, fisheries, mineral deposits, and freshwater aquifers—into economic commodities and waste products. This conversion process typically occurs at rates far exceeding regeneration capacity, constituting capital depletion rather than sustainable yield harvesting. A forest harvested faster than it grows represents liquidation of natural capital, yet conventional accounting systems classify this as income rather than asset depletion. This accounting error systematically obscures ecological unsustainability within economic frameworks.

Forestry economics exemplifies this dynamic. Tropical forest clearing for cattle ranching, soy cultivation, and timber extraction removes carbon-dense ecosystems that require 200-500 years to regenerate, yet economic returns materialize within years. The ecosystem services provided by intact forests—carbon sequestration, hydrological regulation, biodiversity support, and indigenous livelihood provision—receive minimal valuation in market transactions. When forests are converted to pasture or cropland, immediate economic returns appear profitable while ecosystem service losses remain externalized from financial calculations. This economic structure creates systematic incentives for natural capital depletion.

Fisheries economics demonstrates similar patterns. Industrial fishing operations maximize short-term catch volume using capital-intensive technologies (large vessels, sonar, refrigeration) that generate substantial economic value. However, this approach systematically depletes fish stocks below reproduction thresholds, converting renewable resources into non-renewable extraction. The Grand Banks cod fishery collapse exemplifies this dynamic: decades of profitable fishing suddenly ceased when populations collapsed below recovery capacity, eliminating both ecological and economic value. Post-collapse recovery requires 15-20 years minimum, during which fishing communities face economic devastation—a tragedy that could have been prevented through sustainable harvest rates that maintained both ecological and economic value.

Water resource depletion illustrates how economic systems exhaust natural capital with minimal consideration for long-term availability. Aquifer depletion in agricultural regions including the Ogallala Aquifer beneath the US Great Plains and the Indus aquifer system in South Asia represents extraction of ancient water accumulated over millennia. These systems are being depleted over decades, generating irrigation-dependent agriculture that cannot persist beyond aquifer exhaustion. Economic systems optimizing for current production maximize water extraction regardless of depletion trajectories, creating inevitable future scarcity and agricultural collapse. This pattern repeats across resource systems where economic incentives prioritize immediate returns over resource persistence.

Economic Externalities and Environmental Costs

Economic externalities—costs and benefits external to market transactions—represent the primary mechanism through which ecological damage remains unpriced in economic systems. Pollution generation, resource depletion, and ecosystem service loss create environmental costs borne by society and ecosystems rather than economic actors responsible for generating them. This pricing failure systematically undervalues ecologically destructive activities while penalizing ecologically protective practices, creating perverse incentives that accelerate ecological degradation.

Fossil fuel combustion exemplifies externality dynamics. Coal, oil, and natural gas prices reflect extraction and refining costs but exclude climate damages, air pollution health impacts, and ecosystem disruption from extraction. Economic analyses quantifying the full social cost of carbon—including climate damages, health impacts, and ecosystem losses—estimate $100-200 per ton of CO2, yet market prices typically reflect only extraction costs of $5-15 per ton. This pricing gap of 10-40 fold represents a massive subsidy to fossil fuel consumption, making economically rational decisions (from private actor perspectives) ecologically catastrophic. Rectifying this externality through carbon pricing would fundamentally restructure energy systems toward renewable alternatives, yet political economies dependent on fossil fuel revenues resist such price corrections.

Agricultural chemical externalities follow similar patterns. Pesticide and fertilizer applications generate immediate productivity gains captured by farmers as private benefits. However, environmental costs including water contamination, soil degradation, pollinator decline, and human health impacts from chemical residues remain externalized. Quantitative assessments suggest environmental costs of conventional agriculture range from 20-50% of productivity gains, yet these costs remain invisible in commodity prices. Organic and regenerative agricultural practices internalizing these costs often appear more expensive at point of sale despite generating superior long-term ecological and economic value through soil carbon accumulation, biodiversity support, and reduced chemical dependency.

Deforestation economics demonstrates how externality pricing failures drive ecological collapse. Tropical timber harvesting generates economic returns to logging companies and timber-dependent governments, while carbon storage loss, biodiversity elimination, and hydrological disruption create costs borne by global climate systems and local communities. When timber prices reflect only extraction and processing costs while carbon storage value remains externalized, deforestation appears economically rational despite being ecologically catastrophic. Indigenous forest management systems, which have maintained forests while extracting sustainable yields for millennia, receive no economic compensation for carbon storage and biodiversity conservation services they provide. This pricing structure incentivizes forest conversion to agriculture while penalizing forest stewardship.

Sectoral Impacts on Biodiversity

Different economic sectors generate distinct ecological impacts, with agriculture representing the dominant driver of biodiversity loss globally. Industrial agriculture occupies approximately 40% of global land area and generates 80% of global biodiversity loss through habitat conversion, chemical pollution, and simplified crop monocultures that replace diverse native vegetation. Livestock production—requiring feed crops on 77% of global agricultural land while providing only 18% of global calories—represents perhaps the most ecologically inefficient food production system. Cattle ranching drives Amazon deforestation, generates methane emissions exceeding 14% of global greenhouse gas production, and requires freshwater inputs that deplete aquifers. The economic incentive structure favoring cheap meat production externalizes these massive ecological costs.

Energy production systems generate distinct ecological impacts across fossil fuel, hydroelectric, and renewable energy pathways. Coal mining and combustion create landscape-scale habitat destruction, air pollution with documented health impacts affecting hundreds of millions, and climate forcing that alters ecosystems globally. Oil extraction and transportation generate catastrophic spills—the Deepwater Horizon spill released 4.9 million barrels into the Gulf of Mexico, creating ecological damage quantified in hundreds of billions of dollars yet generating minimal financial consequences for responsible corporations. Natural gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing contaminates groundwater, generates induced seismicity, and provides only marginally lower emissions than coal. Hydroelectric dams transform river ecosystems, fragmenting habitat and disrupting sediment transport and fish migration patterns. Renewable energy systems including solar and wind have substantially lower ecological footprints per unit energy, though manufacturing impacts and land-use requirements require careful management to minimize biodiversity loss.

Manufacturing and industrial production generate pollution-driven ecosystem degradation across air, water, and soil pathways. Textile production—the second largest water consumer globally—generates chemical-laden wastewater that contaminates aquatic ecosystems. Electronics manufacturing requires rare earth element extraction creating landscape-scale mining impacts and toxic waste generation. Plastic manufacturing from fossil fuel feedstocks generates persistent pollution that accumulates in marine environments, fragmenting into microplastics that infiltrate food webs. Chemical manufacturing produces persistent organic pollutants that bioaccumulate in organisms and biomagnify through food chains, creating toxicity in apex predators. These sectoral impacts remain largely externalized from production costs, creating economic incentives for pollution-intensive manufacturing in regions with weak environmental regulations.

Tourism and recreation economies, while often perceived as environmentally benign, generate significant ecological impacts through habitat disturbance, pollution, and infrastructure development. Coral reef tourism drives reef degradation through physical damage and pollution, yet generates economic returns that theoretically justify conservation. However, tourism-dependent communities often lack capital to implement protective management, creating scenarios where economic value from degraded reefs exceeds value from intact reefs, perversely incentivizing further degradation. Wilderness tourism drives infrastructure development and human presence into previously intact ecosystems, fragmenting habitat and altering animal behavior. These impacts suggest that economic value generation itself, regardless of sector, creates pressures toward ecosystem simplification and reduced biological complexity.

Pathways to Ecological-Economic Alignment

Achieving sustainability requires fundamentally restructuring economic systems to operate within ecological boundaries while maintaining human wellbeing. Several pathways show promise for reorienting economies toward regenerative rather than extractive relationships with ecosystems. Natural capital accounting represents a foundational approach, adjusting economic metrics to incorporate ecosystem service valuation and resource depletion. When forest carbon storage, water filtration, and biodiversity support receive quantitative valuation in national accounts, economic decisions incorporating these values systematically favor conservation. The United Nations Environment Programme has developed methodologies for natural capital accounting that several nations are implementing, though widespread adoption remains limited by political resistance from extraction-dependent interests.

Carbon pricing mechanisms represent another pathway for internalizing climate costs into economic decisions. Carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems that assign prices to greenhouse gas emissions create economic incentives for emission reduction. Studies from the scientific literature on climate economics demonstrate that carbon prices of $100-200 per ton would make renewable energy economically competitive with fossil fuels at scale, triggering rapid energy system transformation. However, carbon prices implemented globally remain far below cost-reflective levels, typically $5-50 per ton, limiting their effectiveness. Political economy obstacles including fossil fuel industry opposition and energy cost concerns prevent implementation of economically rational carbon prices.

Circular economy models represent a structural approach to reducing material throughput and ecological impact. Rather than extracting virgin resources, processing them into products, and discarding them as waste, circular systems design products for longevity, repairability, and material recovery. This approach reduces resource extraction pressure, minimizes pollution from waste disposal, and creates economic value through material cycling. Successful circular economy implementation requires redesigning production systems, developing reverse logistics infrastructure, and creating markets for recovered materials. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation documents circular economy implementations generating profitability alongside resource reduction, though scaling remains limited by incumbent linear economy interests.

Regenerative agriculture represents a sectoral approach to transforming the largest land-use system toward ecological restoration. Rather than extracting productivity through chemical inputs and monoculture, regenerative approaches build soil carbon, support biodiversity, and reduce chemical dependency through practices including cover cropping, rotational grazing, and polyculture. Research demonstrates that regenerative approaches can match or exceed conventional productivity while building natural capital, yet adoption remains limited by short-term economic incentives favoring conventional approaches. Policy mechanisms including payment for ecosystem services, carbon credits for soil carbon accumulation, and agricultural subsidies redirected toward regenerative practices could accelerate transformation.

Protected area expansion and ecosystem restoration represent direct approaches to maintaining and recovering ecological function. Establishing marine protected areas, expanding forest conservation, and restoring degraded ecosystems generates biodiversity benefits while maintaining ecosystem services. Economic analysis increasingly demonstrates that ecosystem service values often exceed extraction values, particularly when considering long-term sustainability. However, implementing protection requires overcoming economic interests benefiting from extraction, necessitating policy mechanisms that compensate displaced communities and create alternative livelihoods. Indigenous land management systems, which cover 22% of global land while supporting 80% of remaining biodiversity, demonstrate that conservation and sustainable production can coexist when indigenous peoples maintain decision-making authority.

Renewable energy transition represents a critical pathway for addressing climate forcing while maintaining energy services. Solar and wind technologies now provide the lowest-cost electricity in most markets, yet fossil fuel subsidies and infrastructure lock-in slow transition rates. Accelerating renewable energy deployment through policy mechanisms including renewable energy mandates, grid modernization investment, and fossil fuel subsidy elimination would dramatically reduce economic-driven climate forcing. Battery storage technology advancement and grid integration solutions increasingly eliminate technical barriers to high renewable penetration, making transition primarily a political economy question rather than technological constraint.

Economic degrowth frameworks challenge the fundamental assumption that infinite growth remains possible or desirable. Rather than pursuing growth in material throughput, degrowth approaches prioritize wellbeing optimization through reduced consumption, stronger communities, and enhanced leisure time. Research demonstrates that beyond approximately $75,000 annual income per capita, additional income generates minimal wellbeing increases while ecological impacts scale with consumption. Wealthy nations could achieve substantial emission reductions and resource conservation through consumption reduction while maintaining or improving wellbeing through enhanced community relationships, cultural participation, and leisure time. However, degrowth approaches face political opposition from growth-dependent interests and cultural narratives equating consumption with success.

Policy mechanisms including environmental regulations, subsidies restructuring, and international agreements provide governance approaches for implementing ecological-economic alignment. Command-and-control regulations limiting pollution, protecting habitat, and mandating environmental impact assessment have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing ecological damage within regulated sectors. However, regulations often face industry opposition and enforcement challenges in resource-dependent regions. Subsidy restructuring, redirecting the approximately $7 trillion in annual global subsidies for fossil fuels and destructive agriculture toward renewable energy and regenerative practices, would fundamentally alter economic incentives. International agreements including the Paris Climate Agreement and Convention on Biological Diversity establish frameworks for coordinated action, though implementation remains inconsistent and insufficient for meeting stated targets.

Technological innovations including renewable energy, carbon capture, and sustainable materials offer tools for reducing ecological impacts within existing economic structures. However, technological approaches alone cannot achieve sustainability without addressing consumption levels and production efficiency. Rebound effects—where efficiency improvements reduce costs and increase consumption—frequently offset technological improvements, demonstrating that technology without demand management provides insufficient solution. Integrating technological innovation with consumption reduction, circular economy implementation, and regenerative production practices provides more comprehensive pathways toward sustainability.

FAQ

How does economic growth directly cause ecosystem damage?

Economic growth typically increases material throughput, energy consumption, and waste generation, all of which scale with ecological impact. Expanding production requires converting natural ecosystems to economic uses, extracting resources faster than regeneration, and generating pollution that exceeds ecosystem assimilative capacity. While decoupling economic growth from environmental impact remains theoretically possible, empirical evidence shows absolute decoupling—reducing environmental impact while increasing GDP—remains limited to specific sectors and regions. Relative decoupling, reducing environmental impact per unit GDP while maintaining overall growth, more commonly occurs but remains insufficient for achieving sustainability at global scales.

Can markets solve environmental problems without regulation?

Market mechanisms alone cannot solve environmental problems because pricing systems systematically externalize ecological costs. Unregulated markets generate economic incentives for resource depletion, pollution generation, and ecosystem conversion because these activities generate private benefits while costs remain socialized. Carbon pricing, if implemented at cost-reflective levels, could theoretically align market incentives with climate protection. However, establishing politically viable carbon prices at levels reflecting true climate costs remains challenging, and markets require regulatory frameworks preventing externality generation and ensuring property rights protection. Most environmental economists support market mechanisms combined with regulatory safeguards rather than markets alone.

What role do developing nations play in economic-ecosystem relationships?

Developing nations face complex tradeoffs between economic development requirements and ecological protection. Many developing economies depend on natural resource extraction and agricultural exports for income generation and employment, making environmental protection economically challenging without alternative livelihood sources. However, developing nations also bear disproportionate climate change impacts and ecosystem degradation consequences despite contributing minimally to historical emissions. Equitable sustainability pathways require wealthy nations reducing consumption and emissions while providing financial support enabling developing nations to pursue regenerative development. Technology transfer, debt relief, and direct climate finance represent mechanisms for supporting just transitions, yet funding remains far below stated needs.

How can individual consumption choices impact ecosystem protection?

Individual consumption decisions collectively influence market demand, supply chain practices, and corporate behavior. Reducing consumption, choosing sustainably produced products, and supporting regenerative businesses creates market incentives for ecological practices. However, individual action alone cannot achieve sustainability because systemic change requires policy mechanisms, infrastructure transformation, and corporate practice modification beyond individual consumer capacity. Research demonstrates that individual behavior change without policy support rarely generates meaningful environmental impact, while policy-driven transitions can achieve rapid system-wide change. Individual actions remain valuable for building social movements supporting policy change and reducing personal ecological footprints, but should not substitute for systemic transformation requirements.

What timeline remains for achieving ecological-economic alignment?

Climate science indicates that limiting warming to 1.5°C requires global emissions reductions of 45% by 2030 and net-zero by 2050, timelines requiring immediate and accelerated action. Biodiversity loss requires habitat protection and restoration at scales exceeding current commitments, with extinction prevention timelines measured in years for critically endangered species. Water depletion and soil degradation operate on decadal timescales before reaching critical thresholds. These timelines suggest that delayed action substantially increases adjustment costs and reduces options for smooth transitions. However, technological and economic pathways exist for achieving rapid decarbonization and ecological restoration if political will mobilizes resources at required scales. The critical question is not whether sustainability is technically achievable but whether political systems can implement necessary changes before ecological tipping points eliminate options.