Is Almond Milk Bad for the Environment? A Comprehensive Economic and Ecological Analysis

Almond milk has emerged as one of the most popular plant-based dairy alternatives in the past decade, with global market consumption increasing exponentially. However, beneath the sustainability marketing claims lies a complex environmental narrative that challenges the assumption that all plant-based alternatives are inherently eco-friendly. This report examines the multifaceted environmental impacts of almond milk production through an ecological economics lens, analyzing water consumption, biodiversity effects, carbon emissions, and economic externalities that traditional marketing often obscures.

The almond milk industry represents a fascinating case study in how consumer preferences for perceived sustainability can create new environmental pressures. California produces approximately 80% of the world’s almonds, and this concentration has created significant regional ecological challenges. Understanding whether almond milk is genuinely bad for the environment requires moving beyond simplistic narratives to examine the full lifecycle assessment, regional context, and comparative analysis with alternative beverage systems. This investigation reveals that the answer is neither a simple yes nor no, but rather a nuanced understanding of trade-offs and externalities.

Water Consumption and Drought Impact

The water footprint of almond milk production represents perhaps the most significant environmental concern from an ecological economics perspective. Producing one liter of almond milk requires approximately 371 liters of water, making it one of the most water-intensive plant-based beverages available. This figure becomes particularly alarming when contextualized within California’s semi-arid climate and recurring drought conditions.

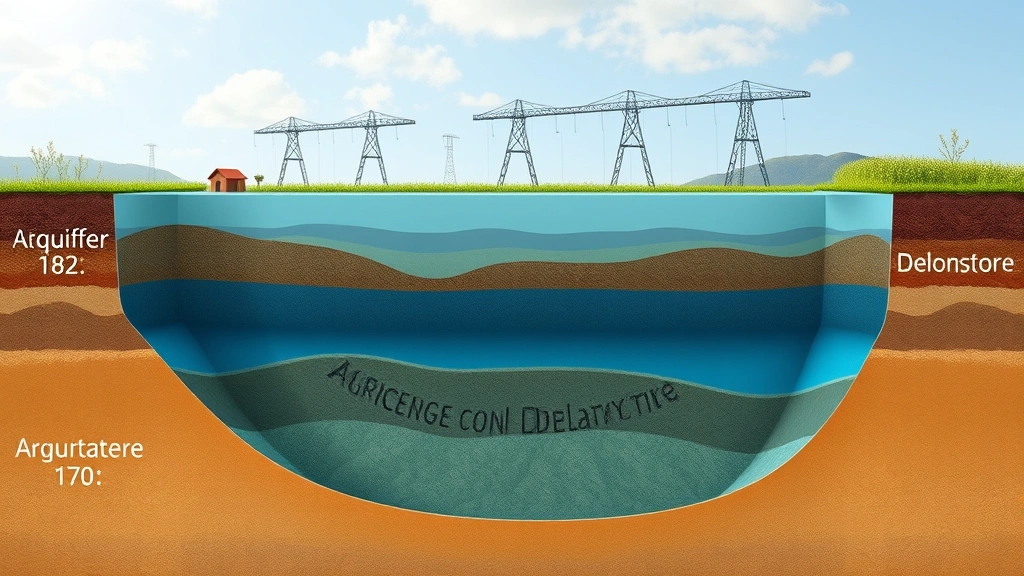

California’s Central Valley, where the majority of American almonds are cultivated, faces chronic water stress. The region depends heavily on groundwater extraction, with almond orchards accounting for approximately 10% of California’s total agricultural water use. This extraction has contributed to significant aquifer depletion, with the Ogallala Aquifer and other critical groundwater reserves declining at unsustainable rates. From an ecological economics standpoint, this represents a classic tragedy of the commons scenario, where individual producers lack incentive to internalize the costs of groundwater depletion.

The economic value of water in agricultural production is deeply underpriced. Most farmers pay a fraction of water’s true shadow price—the value that accounts for long-term scarcity and ecosystem services. This pricing failure creates perverse incentives that encourage overexploitation. A study from the World Bank on agricultural water economics demonstrates that properly pricing water resources could reduce consumption by 15-25% while maintaining profitability. The almond industry exemplifies how market failures in resource pricing lead to environmental degradation that benefits producers while externalizing costs onto society and ecosystems.

The temporal dimension of water consumption adds complexity to this analysis. Almond orchards require consistent water supply during critical growth periods, intensifying pressure during drought years. Between 2012 and 2016, California’s severe drought highlighted this vulnerability, yet almond acreage continued expanding. This paradox reflects how short-term economic incentives can override long-term ecological sustainability, a phenomenon economists call dynamic inefficiency.

Biodiversity Loss and Monoculture Agriculture

Almond cultivation in California has driven extensive habitat conversion, transforming diverse ecosystems into homogeneous agricultural landscapes. The expansion of almond orchards has consumed approximately 1.6 million acres, with much of this land previously supporting native oak woodlands, grasslands, and riparian ecosystems. This human-environment interaction represents a fundamental trade-off between agricultural productivity and biodiversity conservation.

Monoculture almond production creates what ecologists term “ecological deserts”—landscapes with minimal species diversity and reduced ecosystem functionality. These simplified systems exhibit reduced resilience to pests and diseases, necessitating intensive pesticide applications. California almond orchards use approximately 8.5 million pounds of pesticides annually, including neonicotinoids linked to pollinator decline. This chemical dependency reflects the ecological instability inherent in monoculture systems.

The biodiversity impacts extend beyond direct habitat loss. Almond orchards fragment remaining native habitats, creating edge effects that reduce habitat quality for sensitive species. The California Central Valley, once supporting millions of migratory waterfowl, now provides diminished habitat for bird populations. Economic valuation of these biodiversity losses, using methods like contingent valuation or hedonic pricing, suggests annual ecosystem service losses exceeding $500 million regionally.

Pollinator services represent a critical ecosystem function threatened by almond monoculture. Ironically, almond production itself depends entirely on honeybee pollination—approximately 1.5 million hives are transported to California annually for almond bloom. This creates a fragile economic system dependent on managed pollinators while simultaneously degrading wild pollinator populations through pesticide use and habitat loss. This paradox illustrates how extractive agricultural systems can become economically dependent on the very ecosystem services they destroy.

Carbon Footprint and Supply Chain Emissions

While almond milk’s water footprint dominates environmental discourse, its carbon footprint presents a more nuanced picture. Producing one liter of almond milk generates approximately 0.3 to 0.5 kilograms of CO2 equivalent, positioning it favorably compared to dairy milk (approximately 3.2 kg CO2e per liter) but less favorably than some alternatives like oat milk (0.9 kg CO2e per liter).

The carbon analysis reveals significant variation depending on production methodology and supply chain configuration. Almonds grown using conventional irrigation in California have different emission profiles than those using drip irrigation or rain-fed systems. Transportation represents a substantial component—shipping almonds globally adds 0.05-0.1 kg CO2e per liter of final product. This supply chain complexity demonstrates why simple carbon comparisons often mislead consumers regarding true environmental impacts.

Agricultural practices significantly influence emissions. Almonds cultivated using cover cropping and reduced-tillage methods exhibit lower carbon footprints than those using conventional bare-soil management. However, adoption of these practices remains limited due to short-term economic considerations and knowledge barriers. Economic instruments like carbon pricing could incentivize adoption of lower-emission practices, though implementation faces political resistance from agricultural interests.

Processing energy represents another significant carbon component. Almond milk production requires energy for hulling, blanching, and pasteurization. Facilities powered by renewable energy demonstrate substantially lower emissions than those relying on grid electricity. This variability underscores how production location and energy sources create heterogeneous environmental impacts within the industry.

Economic Externalities and Market Failures

The environmental challenges of almond milk production exemplify classic economic externalities—costs imposed on society and ecosystems that are not reflected in market prices. When consumers purchase almond milk at $3-4 per liter, they pay only for private production costs, not the true social cost including water depletion, biodiversity loss, and pollution externalities.

Environmental economists estimate the external costs of California almond production at $0.50-$1.50 per liter when accounting for water depletion, groundwater contamination from agricultural chemicals, habitat loss, and pollinator decline. These unpriced externalities create a significant divergence between private costs and social costs, leading to overproduction from a welfare economics perspective. If these external costs were internalized through mechanisms like Pigouvian taxes or tradeable permits, market prices would increase substantially, reducing consumption and incentivizing efficiency improvements.

The market failure extends beyond individual production decisions to landscape-level resource allocation. California’s water allocation system, rooted in 19th-century water law, fails to account for modern scarcity conditions or ecosystem requirements. This institutional failure perpetuates unsustainable groundwater mining despite economic inefficiency. Ecological economics emphasizes that such institutional structures must be reformed to align economic incentives with ecological constraints.

Subsidies further distort market signals. Agricultural subsidies in California effectively reduce production costs, artificially suppressing prices below true social cost levels. These subsidies, intended to support farm income, inadvertently encourage overproduction of water-intensive crops in water-scarce regions. Removing such subsidies represents a critical policy lever for improving environmental outcomes while enhancing economic efficiency.

Comparative Analysis with Other Milk Alternatives

To properly assess whether almond milk is “bad” for the environment requires comparative analysis with alternative beverage systems. Different plant-based milks present distinct environmental profiles, with no universally superior option across all impact categories.

Oat milk, increasingly popular as an alternative, demonstrates superior water efficiency (requiring approximately 10 liters per liter of final product) compared to almond milk’s 371-liter requirement. However, oat production in some regions relies on intensive pesticide use and monoculture agriculture, presenting different environmental trade-offs. Soy milk, another alternative, faces criticisms regarding deforestation in tropical regions, though most soy for milk production comes from established agricultural lands in temperate regions.

Coconut milk presents water consumption profiles between almond and oat milk, but raises concerns regarding tropical ecosystem conversion and labor practices. Rice milk exhibits relatively favorable water metrics but often comes from regions experiencing significant water stress. Dairy milk, the conventional alternative, demonstrates substantial environmental impacts including methane emissions, feed crop water consumption, and nutrient pollution from manure.

A comprehensive lifecycle assessment comparing these alternatives reveals that no single option optimizes across all environmental dimensions. Water consumption, carbon emissions, biodiversity impacts, and chemical pollution vary significantly depending on production region, agricultural practices, and processing methods. How to reduce carbon footprint through beverage choices requires understanding these nuanced trade-offs rather than adopting simplistic “good” or “bad” categorizations.

The environmental impacts also depend critically on consumption context. In water-rich regions, almond milk’s high water footprint poses less concern than in arid climates. Conversely, in regions with established oat production infrastructure, oat milk minimizes transportation emissions. This geographic heterogeneity demands localized environmental assessment rather than global generalizations.

Policy Solutions and Economic Instruments

Addressing almond milk’s environmental challenges requires multifaceted policy interventions grounded in ecological economics principles. Water pricing reform represents a foundational necessity—implementing marginal cost pricing that reflects true scarcity conditions would substantially reduce consumption while generating revenue for ecosystem restoration.

Tradeable water permits offer market-based mechanisms for achieving environmental targets while preserving economic flexibility. By establishing sustainable groundwater extraction limits and allowing farmers to trade permits, policy can achieve environmental objectives at lower cost than command-and-control regulations. California’s nascent groundwater sustainability agencies represent tentative steps toward such systems, though implementation remains incomplete.

Payment for ecosystem services programs could incentivize conversion of marginal almond acreage to habitat restoration. By compensating farmers for biodiversity conservation and water retention services, policy can address market failures while supporting rural economies. Environment examples from conservation payment programs demonstrate feasibility of such approaches.

Agricultural subsidy reform constitutes another critical policy lever. Eliminating or redirecting subsidies toward sustainable practices would improve price signals, making water-intensive crops less profitable in water-scarce regions. This reform faces significant political opposition but represents economically efficient policy aligned with environmental objectives.

Carbon pricing mechanisms could incentivize adoption of lower-emission production practices. By establishing carbon prices reflecting the social cost of emissions, policy creates economic incentives for farmers to adopt renewable energy, improve irrigation efficiency, and reduce chemical inputs. UNEP research demonstrates carbon pricing effectiveness in agricultural contexts.

Certification and labeling standards can address information asymmetries, enabling consumers to make environmentally informed choices. Comprehensive environmental labels accounting for water, carbon, and biodiversity impacts would help consumers understand true environmental costs. Research from environmental economics journals suggests such labels significantly influence purchasing behavior.

Innovation policy supporting development of water-efficient almond varieties and cultivation techniques offers technological pathways toward sustainability. Investment in agricultural research addressing climate adaptation and water efficiency could reduce environmental impacts while maintaining productivity. Renewable energy adoption in processing facilities represents another technological opportunity.

Regional water management integration across agricultural, urban, and environmental sectors enables holistic optimization. Ecological economics emphasizes that sustainable solutions require systems-level thinking acknowledging interconnections between economic activities and natural systems. California’s water challenges demand integrated policy addressing agricultural, urban, and environmental water demands simultaneously.

FAQ

Is almond milk worse than dairy milk environmentally?

Almond milk presents lower carbon emissions than dairy milk but higher water consumption in most contexts. Dairy milk generates approximately 3.2 kg CO2e per liter versus 0.3-0.5 kg CO2e for almond milk, but requires substantially less water (628 liters per liter versus 371 liters). The comparison depends on prioritized environmental concerns and regional context. In water-scarce regions, almond milk’s water footprint presents greater concern than dairy’s carbon emissions, while in carbon-conscious policy environments, dairy’s emissions become more problematic.

What’s the most environmentally friendly milk alternative?

No universally superior option exists across all environmental dimensions. Oat milk demonstrates superior water efficiency and relatively low carbon emissions when produced in temperate regions with established infrastructure. However, soy milk, pea milk, and other alternatives present different environmental profiles depending on production location and practices. The most environmentally friendly choice depends on local agricultural context, water availability, and prioritized environmental concerns.

Can almond milk production become sustainable?

Yes, but requires systemic changes in water pricing, agricultural practices, and regional resource management. Implementation of sustainable irrigation technologies, transition to regenerative agriculture practices, and adoption of water-efficient almond varieties could substantially reduce environmental impacts. However, these improvements require policy interventions correcting market failures and economic incentives currently driving unsustainable practices.

How much water does almond milk actually use?

Producing one liter of almond milk requires approximately 371 liters of water from irrigation. This includes water for tree establishment, maintenance, and nut production. Variation exists depending on climate conditions, irrigation methods, and rainfall patterns. In California’s drought-prone climate, this water consumption represents a significant sustainability concern given regional water scarcity.

Should I stop drinking almond milk?

Individual consumption decisions should consider personal environmental priorities, local water conditions, and available alternatives. In water-stressed regions, switching to oat or pea milk reduces environmental impact. In regions with abundant water but high carbon emissions, almond milk’s lower carbon footprint may represent a preferable choice. Ultimately, addressing almond milk’s environmental challenges requires policy intervention and industry transformation rather than individual consumer boycotts.

What does ecological economics say about almond milk?

Ecological economics analysis reveals that market prices for almond milk fail to reflect true social and environmental costs. Water and ecosystem service externalities create divergence between private production costs and social costs. This represents a classic market failure requiring policy intervention through mechanisms like water pricing reform, ecosystem service valuation, and subsidy elimination. Ecological economics emphasizes that sustainable agriculture requires institutional changes aligning economic incentives with ecological constraints.