Linux Environment Variables: A Beginner’s Guide to System Configuration and Ecological Computing

Environment variables form the backbone of Linux system configuration, acting as dynamic named values that control how applications behave and interact with the operating system. Understanding how to set, modify, and manage these variables is essential for anyone working with Linux systems, from system administrators to software developers. This guide bridges technical computing practices with broader considerations about sustainable technology use and efficient resource management—principles that align with ecological economics and environmental stewardship in the digital age.

The relationship between proper system configuration and computational efficiency mirrors the interconnected nature of environment and society. Just as ecosystems require balanced interactions between components, Linux systems require properly configured variables to function optimally, reducing wasted computational resources and energy consumption. By mastering environment variables, you contribute to more efficient computing practices that benefit both your system’s performance and broader environmental goals.

What Are Environment Variables?

Environment variables are key-value pairs that store information about your system’s configuration and user preferences. They provide a mechanism for programs to access system-wide or user-specific settings without requiring hard-coded values. Think of them as configuration containers that applications query to understand how they should operate within your computing environment.

Every time you open a terminal or launch an application, your system automatically loads these variables into memory, making them accessible to all child processes. This hierarchical approach ensures that settings cascade efficiently through your system, much like how humans affect the environment through cascading systemic interactions. When you set an environment variable, you’re essentially defining a rule that governs how your system behaves, similar to how environmental policies shape human interaction with natural systems.

The power of environment variables lies in their flexibility. Instead of modifying application code or configuration files repeatedly, you can change a single variable value and affect how multiple programs behave. This efficiency principle extends to resource management—fewer configuration changes mean less system overhead and computational waste.

Types of Environment Variables

Linux distinguishes between two primary categories of environment variables: system-wide variables and user-specific variables. Understanding this distinction helps you implement proper configuration management for your needs.

System-Wide Variables apply to all users on the system and are typically defined in global configuration files like /etc/environment, /etc/profile, or /etc/bash.bashrc. These variables establish baseline configurations that affect system behavior for everyone, similar to how environmental regulations create baseline standards for all human-environment interaction.

User-Specific Variables apply only to individual users and are defined in personal configuration files like ~/.bashrc, ~/.bash_profile, or ~/.zshrc. These allow customization without affecting other users, providing the flexibility needed for diverse computing needs and preferences.

Session Variables exist only for the duration of your current terminal session. Once you close the terminal, these variables disappear, making them useful for temporary configurations or testing.

How to View Environment Variables

Before setting new variables, you should understand how to view existing ones. This foundational skill helps you avoid conflicts and understand your system’s current configuration.

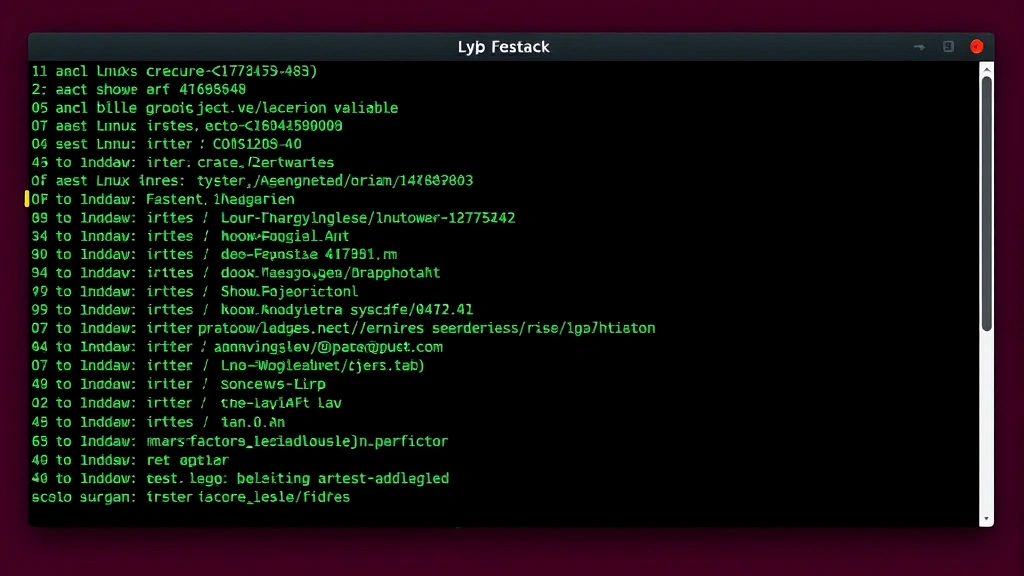

The env command displays all environment variables currently set in your session:

env

This produces a comprehensive list showing every variable and its value. If you want to search for a specific variable, combine it with grep:

env | grep VARIABLE_NAME

The echo command displays the value of a specific variable by prefixing it with a dollar sign:

echo $HOME

This returns your home directory path. The dollar sign tells the shell to substitute the variable’s value rather than printing the literal text.

For a more organized view, the printenv command presents variables in an easily readable format:

printenv

You can also check a specific variable:

printenv PATH

These viewing commands are essential diagnostic tools, allowing you to understand your system’s configuration state before making changes—much like conducting environmental assessments before implementing sustainability initiatives.

Setting Temporary Environment Variables

Temporary environment variables persist only for your current session and are useful for testing configurations or running commands with specific settings without permanent changes.

To set a temporary variable, use the export command:

export VARIABLE_NAME="value"

For example:

export CUSTOM_PATH="/usr/local/custom"

You can verify the variable was set:

echo $CUSTOM_PATH

This should return /usr/local/custom.

Variables can contain various data types—strings, numbers, or paths. You can also reference other variables within your new variable:

export EXTENDED_PATH="$PATH:/usr/local/custom"

This appends a new directory to your existing PATH variable without losing previous values. This approach exemplifies efficient resource management—building upon existing configurations rather than replacing them entirely.

To unset a temporary variable, use:

unset VARIABLE_NAME

After closing your terminal session, all temporary variables disappear automatically.

Setting Permanent Environment Variables

Permanent environment variables persist across sessions and system restarts. Setting them requires modifying configuration files, and your choice of file depends on whether you want user-specific or system-wide settings.

User-Specific Permanent Variables

For individual user configuration, edit your shell’s initialization file. If you use Bash, edit ~/.bashrc or ~/.bash_profile:

nano ~/.bashrc

Add your variable definition at the end of the file:

export MY_VARIABLE="my_value"

Save the file (Ctrl+O, Enter, Ctrl+X in nano) and reload your configuration:

source ~/.bashrc

Alternatively, log out and log back in to apply changes automatically.

For Zsh users, edit ~/.zshrc instead:

nano ~/.zshrc

Add your variable and reload:

source ~/.zshrc

System-Wide Permanent Variables

To set variables for all users, edit /etc/environment (requires sudo access):

sudo nano /etc/environment

Add variables in the format:

SYSTEM_VARIABLE="value"

Note: Variables in /etc/environment don’t use the export keyword. Save and reload:

source /etc/environment

Alternatively, edit /etc/profile for shell-specific system variables:

sudo nano /etc/profile

Add your export statements and save. These changes affect all users on your system.

This hierarchical configuration approach mirrors ecological systems where local and global regulations work together to create comprehensive environmental management strategies.

Common Environment Variables Explained

Understanding frequently-used variables helps you navigate Linux systems more effectively and recognize opportunities for optimization.

PATH

The PATH variable contains directories where the system searches for executable programs. When you type a command, the shell searches these directories in order. A properly configured PATH ensures efficient command discovery and prevents security vulnerabilities.

echo $PATH

HOME

This variable stores your home directory path, typically /home/username. Applications use this to locate user-specific configuration files and data.

echo $HOME

USER

Contains your current username, useful for scripts and applications that need to identify the active user.

SHELL

Specifies your default shell interpreter (e.g., /bin/bash, /bin/zsh), determining how your terminal processes commands.

LANG and LC_*

These variables control language and locale settings, affecting how applications display text, format dates and numbers, and handle character encoding. Proper locale configuration ensures international compatibility and accessibility.

EDITOR

Defines your default text editor for commands that require one. Many applications respect this setting:

export EDITOR="nano"

PYTHONPATH

For Python developers, this variable specifies directories containing Python modules, extending where Python searches for importable packages.

LD_LIBRARY_PATH

Tells the system where to find shared libraries, critical for applications linking to dynamic libraries at runtime.

Understanding these variables enables more efficient system configuration and troubleshooting, reducing the need for resource-intensive debugging processes.

Best Practices and Security Considerations

Proper environment variable management requires attention to security, maintainability, and system health. These practices ensure your system remains efficient and secure, aligned with principles of sustainable computing.

Use Descriptive Names

Variable names should clearly indicate their purpose. Instead of VAR1, use DATABASE_HOST or API_KEY. This improves code readability and reduces errors when managing multiple variables.

Document Your Variables

Add comments in your configuration files explaining each variable’s purpose:

# Database connection settings

export DB_HOST="localhost"

export DB_PORT="5432"

Avoid Hardcoding Sensitive Data

Never store passwords, API keys, or tokens directly in environment variable files. Instead, use secure credential management systems. If temporary sensitive variables are necessary, unset them immediately after use:

export API_KEY="secret123"

// use API_KEY

unset API_KEY

Use Quotes for Values with Spaces

Always quote variable values containing spaces:

export DESCRIPTION="This is a multi-word value"

Order Matters in PATH

The system searches PATH directories in order. Place frequently-used directories first to reduce search time and improve efficiency:

export PATH="/usr/local/bin:$PATH"

Test Before Making Permanent Changes

Always test variables in a temporary session before adding them to permanent configuration files. This prevents system-wide issues from misconfigurations.

Maintain Backups

Before editing critical configuration files like /etc/environment or /etc/profile, create backups:

sudo cp /etc/environment /etc/environment.backup

This allows quick recovery if something goes wrong, minimizing system downtime.

Regular Audits

Periodically review your environment variables to identify obsolete or redundant settings. Removing unnecessary variables reduces system complexity and potential conflicts, much like how environmental restoration involves removing invasive species to restore ecosystem balance.

These practices reflect the broader importance of sustainable environmental practices in technology. Just as ecological systems require careful stewardship, computing systems benefit from thoughtful configuration management that respects resource constraints and security principles.

FAQ

What’s the difference between export and setting a variable without export?

Without export, a variable is available only in your current shell. With export, child processes inherit the variable. For most purposes, use export to ensure variables propagate to programs you run.

How do I permanently add to my PATH?

Edit your shell’s configuration file (~/.bashrc or ~/.zshrc) and add: export PATH="$PATH:/your/new/path". The $PATH preserves existing directories while adding your new one.

Can I set environment variables in a script?

Yes, but variables set in a script don’t affect your current shell unless you source the script: source script.sh. Running it normally creates a child process where variables disappear after execution.

Why isn’t my environment variable working?

Common causes include: not sourcing your configuration file after changes, using incorrect syntax, forgetting the export keyword, or setting it in the wrong file. Verify with echo $VARIABLE_NAME and check your shell type with echo $SHELL.

How do I remove an environment variable?

For temporary variables in your current session, use unset VARIABLE_NAME. For permanent variables, edit the configuration file where you defined it and remove the export line, then source the file again.

Are environment variables case-sensitive?

Yes, Linux treats PATH and path as completely different variables. By convention, environment variable names use uppercase letters.