Human Impact on Ecosystems: A Scientific Overview

Human civilization has fundamentally reshaped Earth’s ecosystems at an unprecedented scale and velocity. Over the past two centuries, industrial expansion, agricultural intensification, and urbanization have triggered cascading ecological transformations that affect everything from atmospheric composition to soil microbial communities. The scientific consensus is unequivocal: human activities now constitute the dominant ecological force on the planet, rivaling geological processes in their capacity to alter planetary systems. This era—termed the Anthropocene—reflects humanity’s outsized influence on global biogeochemical cycles, biodiversity patterns, and ecosystem functioning.

Understanding the mechanisms through which humans affect the environment requires an interdisciplinary lens combining ecology, economics, climatology, and social sciences. The pathways of human impact operate across multiple scales: local degradation of watersheds, regional air pollution events, and planetary-scale climate disruption. These impacts manifest not as isolated phenomena but as interconnected feedback loops where one disturbance amplifies others. For instance, deforestation simultaneously reduces carbon sequestration capacity, eliminates wildlife habitat, destabilizes local hydrological cycles, and concentrates atmospheric carbon dioxide—each consequence triggering secondary ecological effects. This comprehensive overview synthesizes current scientific understanding of anthropogenic ecosystem impacts, examining their mechanisms, magnitudes, and potential trajectories.

Climate Change and Atmospheric Disruption

Anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions represent perhaps the most extensively documented human impact on Earth systems. Since industrialization, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations have increased by 50 percent, from approximately 280 parts per million to over 420 parts per million. This elevation results primarily from fossil fuel combustion, which annually releases roughly 37 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent into the atmosphere. The radiative forcing effect of accumulated greenhouse gases has already increased global mean surface temperatures by approximately 1.1 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial baselines, with further warming locked into the climate system regardless of immediate mitigation efforts.

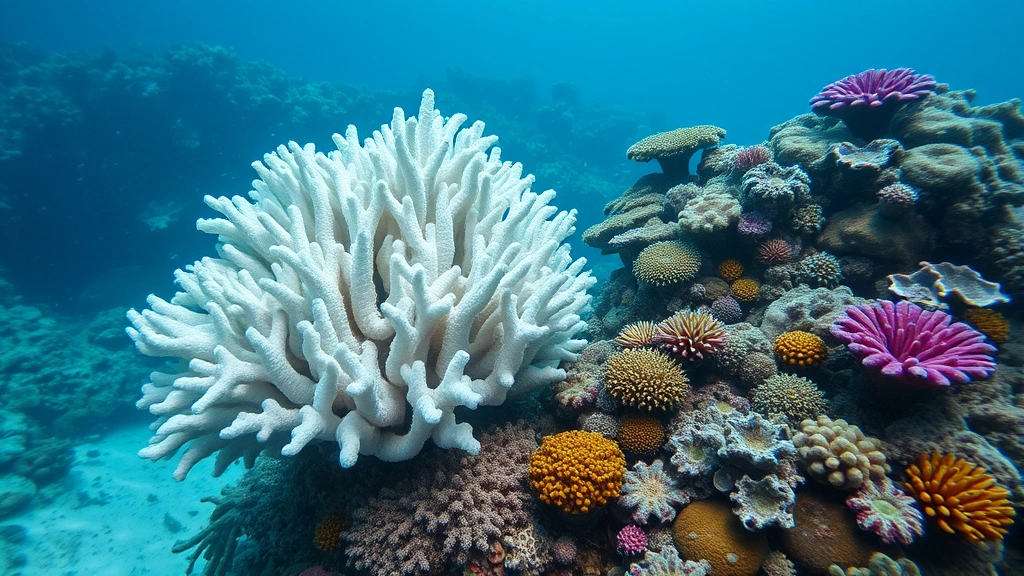

The climate disruption mechanism operates through straightforward thermodynamic principles: greenhouse gases absorb and re-radiate infrared radiation, trapping heat in the lower atmosphere. However, the consequences extend far beyond simple temperature elevation. Reduced carbon footprints through lifestyle modifications represent one mitigation pathway, yet systemic change requires comprehensive energy infrastructure transformation. Climate change destabilizes precipitation patterns, intensifies extreme weather events, disrupts phenological synchronization between predators and prey, and elevates ocean acidification rates. Coral reef ecosystems face existential threats from thermal bleaching, while polar regions experience accelerated ice sheet disintegration, triggering sea-level rise that threatens coastal human settlements housing over 600 million people.

Research from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change demonstrates that atmospheric disruption operates as a multiplier for other anthropogenic impacts. Warming temperatures alter ecosystem carrying capacities, shift species ranges poleward and upslope, and create novel ecological communities with uncertain stability properties. The feedback mechanisms—such as reduced albedo from Arctic sea ice loss or increased methane emissions from thawing permafrost—create self-reinforcing cycles that amplify initial warming signals.

Biodiversity Loss and Habitat Destruction

Global biodiversity is contracting at rates estimated between 100 and 1,000 times background extinction rates. Approximately 1 million species face extinction risk within decades, with habitat destruction constituting the primary driver. The conversion of natural ecosystems to agricultural lands, urban areas, and infrastructure corridors has fragmented remaining habitats into isolated patches insufficient to sustain viable populations of wide-ranging species. Tropical rainforests, which harbor roughly 50 percent of terrestrial species despite occupying only 6 percent of land area, are cleared at approximately 10 million hectares annually.

Habitat loss operates through multiple mechanisms: direct conversion eliminates species outright, habitat fragmentation isolates populations reducing genetic diversity and increasing extinction vulnerability, and edge effects degrade microhabitats at fragment boundaries. The scientific definition of environment encompasses interconnected biotic and abiotic components whose disruption cascades through food webs and ecological networks. Apex predator removal through hunting and habitat loss triggers trophic cascades where herbivore populations explode, overconsuming vegetation and destabilizing entire ecosystem structures. Pollinator decline—driven by insecticide exposure, monoculture agriculture, and habitat loss—threatens crop production for approximately 75 percent of global food crops.

The economic dimensions of biodiversity loss remain inadequately incorporated into policy frameworks. Ecosystem services including pollination, water purification, climate regulation, and nutrient cycling generate trillions of dollars in annual economic value, yet these services remain largely unpriced in market transactions. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation impose annual economic costs exceeding $4 trillion globally, yet these externalities remain invisible to conventional GDP accounting.

Pollution and Chemical Contamination

Chemical pollution permeates every ecosystem compartment: atmospheric aerosols, aquatic sediments, soil profiles, and even remote polar regions register anthropogenic chemical signatures. Persistent organic pollutants including polychlorinated biphenyls, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances accumulate in organism tissues through bioaccumulation, reaching concentrations millions of times higher than ambient environmental levels. These compounds exhibit remarkable environmental persistence—some DDT residues from mid-twentieth century applications remain bioavailable in contemporary ecosystems.

Eutrophication from agricultural nutrient runoff creates hypoxic dead zones in coastal waters where dissolved oxygen depletion eliminates aerobic life. The Mississippi River dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico encompasses approximately 6,000 square miles annually, driven by nitrogen and phosphorus runoff from Midwestern agricultural regions. Heavy metal contamination from industrial processes, mining, and waste disposal persists indefinitely in ecosystems, with lead, mercury, and cadmium demonstrating particular neurotoxicity in developing organisms. Microplastic pollution—originating from synthetic textile degradation, tire wear, and plastic waste fragmentation—now contaminates virtually every marine environment, from surface waters to abyssal depths.

The patterns of human environment interaction reveal how production and consumption systems generate pollution externalities. Industrial agriculture’s reliance on synthetic pesticides and herbicides eliminates non-target organisms, disrupting pest predator relationships and creating pesticide-resistant pest populations. Acid rain from sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions acidifies freshwater ecosystems, dissolving calcium from fish skeletons and inhibiting reproduction in sensitive species.

Resource Depletion and Overexploitation

Humanity currently appropriates approximately 25 percent of global net primary productivity—the total energy fixed by photosynthesis available for ecosystem functions. This appropriation rate leaves insufficient resources for non-human species, effectively squeezing biodiversity from the biosphere through resource competition. Fisheries deplete marine stocks at unsustainable rates, with approximately 35 percent of global fish stocks harvested at biologically unsustainable levels. Bottom trawling obliterates benthic communities accumulated over millennia, with recovery timescales measured in centuries if possible at all.

Groundwater depletion in agricultural regions far exceeds natural recharge rates, with the Ogallala Aquifer beneath the American Great Plains declining at approximately 0.3 meters annually. This depletion trajectory renders agricultural systems unsustainable within decades without fundamental transformation. Soil degradation through erosion, salinization, and organic matter depletion reduces productive capacity in approximately 25 percent of global agricultural lands. Deforestation simultaneously depletes timber resources while eliminating the forest ecosystem itself, replacing complex multi-layered communities with simplified plantation monocultures or bare ground.

The economic logic driving resource overexploitation reflects the World Bank’s analysis of natural capital depletion in national accounting systems. Conventional economic frameworks treat resource extraction as income rather than capital depletion, incentivizing unsustainable harvest rates. Fisheries subsidies totaling approximately $35 billion annually perpetuate overcapacity in fishing fleets, maintaining harvest rates well above ecosystem regeneration capacity. Agricultural subsidies similarly incentivize intensive monoculture production rather than regenerative practices that restore soil carbon and ecosystem function.

Urban Expansion and Land-Use Change

Urbanization represents one of the most dramatic landscape transformations in human history. Global urban areas have expanded from approximately 1 percent of terrestrial land in 1800 to roughly 3 percent currently, yet this modest percentage figure obscures the ecological significance of urban areas. Urban zones fragment habitats, introduce invasive species through global trade networks, concentrate pollution sources, and create heat island effects where urban temperatures exceed surrounding rural areas by 5-7 degrees Celsius. The impervious surfaces characteristic of urban development—concrete, asphalt, roofing materials—eliminate soil infiltration, increasing stormwater runoff that overwhelms natural water treatment capacity and degrades aquatic habitats.

Agricultural land conversion drives the largest terrestrial ecosystem transformation globally. Approximately 38 percent of ice-free terrestrial land is devoted to agriculture, with grazing lands occupying roughly 26 percent of terrestrial area. This agricultural expansion has eliminated approximately 68 percent of historical wildlife populations since 1970, according to the Living Planet Index. Monoculture agriculture replaces biodiverse natural communities with simplified systems dependent on external chemical inputs and prone to pest outbreaks and disease epidemics. The environmental impacts of resource extraction and infrastructure development extend throughout supply chains from production through consumption and disposal.

Land-use change simultaneously contributes to climate disruption through vegetation carbon stock elimination. Tropical forest conversion to pasture or cropland releases stored carbon while eliminating ongoing carbon sequestration. The carbon payback period—the time required for agricultural productivity to offset conversion carbon losses—exceeds 100 years for most tropical forest conversions, yet conversion economics ignore this temporal dimension of carbon accounting.

Interconnected Ecological Consequences

The preceding impact categories do not operate in isolation; rather, they generate multiplicative consequences through ecosystem-level interactions. Climate warming accelerates pest and pathogen reproduction rates, expanding their geographic ranges and increasing disease pressure on host populations weakened by habitat fragmentation. Pollution-induced immune suppression increases disease susceptibility in stressed animal populations. Nutrient enrichment from agricultural runoff promotes algal blooms that subsequently decompose, generating hypoxic conditions that compound climate warming impacts on aquatic organisms with limited thermal tolerance.

Ecosystem resilience—the capacity to absorb disturbance while maintaining functional integrity—declines as multiple stressors accumulate. Ecosystems experiencing simultaneous climate warming, habitat fragmentation, pollution exposure, and resource extraction demonstrate dramatically reduced capacity to absorb additional perturbations. The Amazon rainforest, once considered resilient to deforestation, increasingly approaches a tipping point beyond which forest-savanna transition becomes irreversible. Such regime shifts represent catastrophic transitions where ecosystems shift to alternative stable states with fundamentally different species composition, productivity, and ecosystem services.

Trophic network disruption cascades through food webs in complex patterns difficult to predict from single-species perspectives. Pollinator decline reduces reproductive success in flowering plants, eliminating seed production and affecting granivorous birds and rodents. Apex predator loss through hunting alters herbivory pressure, potentially triggering vegetation state changes that affect water cycling, carbon sequestration, and erosion dynamics. These indirect effects often exceed direct impacts in magnitude, suggesting that ecosystem management must explicitly consider network connectivity and feedback mechanisms.

Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services

Contemporary ecological economics recognizes that ecosystem services—the benefits humans derive from natural systems—constitute genuine economic value equivalent to or exceeding human-produced capital. Pollination services generate approximately $15 billion annually in agricultural value. Water purification by wetlands and forests provides treatment equivalent to expensive engineered infrastructure. Carbon sequestration by forests and wetlands generates climate regulation value that markets are increasingly attempting to price through carbon credit mechanisms. Coastal wetlands provide nursery habitat for commercially important fish species, with economic value estimated at $5,000-$500,000 per hectare annually depending on local market conditions.

The challenge of ecosystem service valuation extends beyond technical economic methodology to fundamental philosophical questions about nature’s intrinsic value. Utilitarian frameworks valuing ecosystems only for human benefit risk justifying ecosystem destruction if alternative goods provide higher monetary returns. However, ecosystem service valuation frameworks have proven politically effective in conservation policy, generating economic arguments for habitat protection that complement ecological and ethical rationales. Payment for ecosystem services schemes—compensating landowners for conservation activities—leverage market mechanisms to internalize previously externalized ecosystem benefits.

Research in Nature Reviews and similar ecological economics journals demonstrates that ecosystem service provision depends critically on maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem structure. Simplified ecosystems provide reduced service quantities and demonstrate reduced temporal stability in service delivery. Agricultural systems reliant on synthetic inputs provide higher short-term productivity but at the cost of long-term soil degradation, biodiversity loss, and water quality impairment. Regenerative agriculture systems integrating livestock, crop rotation, and reduced tillage restore soil carbon, enhance water infiltration, and support biodiversity while maintaining economic productivity.

The transition toward genuine full-cost accounting that incorporates ecosystem service values and natural capital depletion remains incomplete in most national economic frameworks. Adjusted net national income calculations incorporating resource depletion and environmental degradation reveal that many nations reporting positive GDP growth simultaneously deplete natural capital, rendering long-term economic sustainability questionable. The UNEP’s environmental economics research emphasizes that true economic development requires decoupling growth from resource depletion and environmental degradation—a transformation requiring fundamental restructuring of production and consumption systems.

FAQ

What is the single largest human impact on ecosystems?

Habitat destruction through land-use change constitutes the primary driver of biodiversity loss and ecosystem disruption globally. Agricultural expansion, urban development, and infrastructure construction convert natural ecosystems to simplified human-dominated systems at approximately 10 million hectares annually. While climate change represents an increasingly dominant stressor, habitat loss remains the leading extinction driver for terrestrial species.

How do humans affect the environment through everyday activities?

Individual consumption patterns generate cumulative environmental impacts through multiple pathways: fossil fuel combustion for transportation and heating contributes to climate disruption; food consumption drives agricultural expansion and associated habitat destruction; synthetic product use generates pollution externalities; and waste disposal contaminates soil and water systems. The average person in developed nations appropriates resources and generates waste equivalent to 3-5 planetary Earths if universalized globally, demonstrating the unsustainability of current consumption patterns.

Can ecosystem damage be reversed?

Ecosystem recovery depends critically on disturbance magnitude and duration. Some ecosystems demonstrate remarkable regeneration capacity when stressors are removed—wetlands can recover within decades, forests within centuries. However, ecosystems experiencing multiple simultaneous stressors or regime shifts to alternative stable states face much longer recovery timescales if recovery is possible at all. Preventing degradation through conservation remains far more effective and economical than attempting restoration following severe ecosystem collapse.

What is the economic cost of environmental degradation?

Annual economic costs from biodiversity loss, ecosystem degradation, and pollution exceed $4 trillion globally according to UNEP estimates, representing approximately 5 percent of global economic output. These costs include lost agricultural productivity, healthcare expenses from pollution exposure, damages from extreme weather events, and reduced ecosystem service provision. However, these estimates likely undervalue true costs given incomplete data on long-term consequences and non-market ecosystem services.

How does human impact on ecosystems affect human societies?

Ecosystem degradation directly undermines human wellbeing through reduced food security, increased water scarcity, amplified disease risk, and climate-driven displacement. Approximately 3 billion people depend directly on biodiversity for livelihoods. Approximately 4 billion people face severe water scarcity seasonally. Ecosystem services including water purification, flood regulation, and pollination provide foundations for human civilization; their degradation threatens fundamental prerequisites for human survival and prosperity.