How Economy Impacts Ecosystems: Latest Insights and Examples for Human Environment Interaction

The relationship between economic activity and ecosystem health represents one of the most critical challenges of our time. As global economies expand and industrial production intensifies, the natural systems that support all life face unprecedented pressures. From deforestation driven by agricultural commodities to ocean acidification caused by fossil fuel emissions, economic decisions ripple through ecosystems with profound consequences. Understanding these connections is essential for policymakers, business leaders, and citizens seeking sustainable pathways forward.

Recent research reveals that approximately 50% of global GDP depends on ecosystem services, yet current economic models fail to account for environmental degradation costs. This paradox—where economic growth often comes at the expense of natural capital—demands urgent attention and systemic reform. By examining concrete examples of human environment interaction, we can better understand how economic structures shape ecological outcomes and identify opportunities for more sustainable alternatives.

The Economic-Ecological Nexus: Fundamentals and Framework

Economic systems and ecosystems operate through fundamentally different logics, yet they remain inextricably linked. Traditional economics treats nature as an infinite resource base and waste sink, assumptions that collapse under scrutiny. The natural capital approach attempts to bridge this gap by valuing ecosystem services—pollination, water purification, carbon sequestration, climate regulation—in monetary terms. However, this framework has limitations, as not all ecological functions can be meaningfully priced.

The concept of definition of environment in science encompasses the physical, chemical, and biological conditions surrounding organisms. When economic activity alters these conditions—through resource extraction, pollution, or habitat modification—ecosystem functions degrade. A groundbreaking World Bank study found that environmental degradation costs developing nations approximately 4-5% of their annual GDP, a hidden economic burden rarely reflected in standard accounting practices.

The circular economy model offers a contrasting vision, where materials cycle continuously and waste becomes input. Yet transitioning from linear “take-make-dispose” economies requires fundamental restructuring of production and consumption patterns. Current global economic incentives favor extraction and externalization of costs rather than circular approaches, creating persistent misalignment between economic growth and ecological stability.

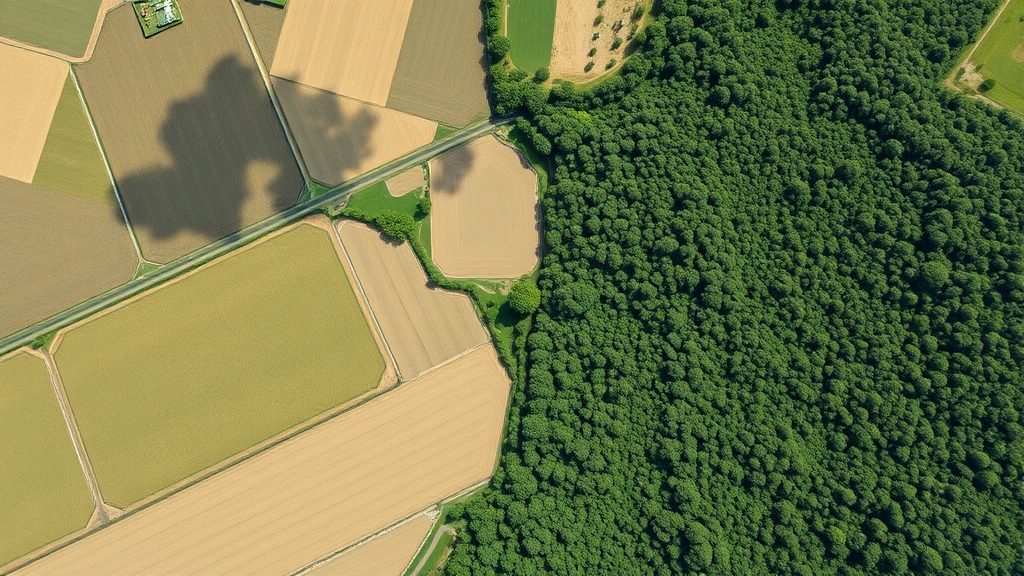

Agriculture and Land Use: Economic Drivers of Ecosystem Change

Agriculture represents humanity’s most extensive use of land, occupying approximately 38% of Earth’s terrestrial surface. The economic logic of industrial agriculture—maximizing yield per hectare through monoculture, synthetic inputs, and mechanization—has generated remarkable productivity gains. Global cereal production has tripled since 1960, enabling food security for billions. Yet this success masks profound ecological costs that economic accounting typically ignores.

Monoculture farming eliminates habitat heterogeneity, reducing biodiversity by 50-90% compared to natural ecosystems. The economic incentive structure rewards single-crop specialization because it simplifies mechanization, standardizes inputs, and enables economies of scale. However, this approach depletes soil organic matter, increases pest vulnerability, and requires escalating chemical inputs. Nitrogen fertilizer use has increased tenfold since 1960, with approximately 40% leaching into waterways and contributing to 400+ dead zones globally. The economic cost of treating nitrogen-polluted water, lost fisheries, and human health impacts far exceeds the cost of alternative farming methods, yet farmers face immediate economic pressure favoring conventional approaches.

Palm oil production exemplifies economic-ecological conflict at scale. Expanding at 2 million hectares annually, palm plantations drive deforestation in Southeast Asia, destroying habitat for orangutans, tigers, and countless endemic species. From an economic perspective, palm oil generates substantial GDP, export revenue, and employment. From an ecological perspective, it represents catastrophic habitat loss and carbon release. UNEP estimates that incorporating ecosystem service losses and climate impacts would reduce palm oil’s economic viability by 50-70%.

Cattle ranching presents similar dynamics. Livestock production occupies 77% of agricultural land globally while providing only 18% of calories and 37% of protein. The economic incentives—subsidies, market demand, land availability—encourage expansion into biodiverse regions like the Amazon. The ecological cost includes deforestation, soil degradation, methane emissions, and biodiversity loss. Learning about how to reduce carbon footprint includes understanding agricultural system impacts and potential transitions toward plant-forward diets.

Industrial Production and Pollution Externalities

Industrial manufacturing drives economic growth while generating pollution that damages ecosystems and human health. This dynamic reflects a fundamental market failure: polluters bear none of the costs of environmental damage, creating economic incentives for excessive pollution. A factory producing textiles generates profits for owners and shareholders, but water pollution, air emissions, and waste externalities are borne by downstream communities and ecosystems.

The textile industry exemplifies this pattern. Producing one kilogram of cotton requires approximately 10,000 liters of water and generates substantial chemical pollution. The economic value captured by manufacturers and retailers far exceeds environmental costs they pay. Sustainable fashion brands represent attempts to internalize these costs, though they remain niche markets. Mainstream economics incentivizes outsourcing production to regions with minimal environmental regulation, externalizing costs geographically.

Electronic waste (e-waste) represents another critical example. Rapid technological obsolescence—driven by economic incentives for consumption and planned obsolescence—generates 60 million tons of e-waste annually. Recycling is economically inefficient in wealthy nations, so much e-waste is shipped to developing countries where informal recycling releases toxins into soil and water. The economic benefit of rapid technology cycles accrues to manufacturers and consumers in wealthy nations; ecological and health costs concentrate in developing regions.

Chemical pollution demonstrates how economic externalities accumulate. Approximately 350,000 synthetic chemicals exist globally, with only a fraction adequately tested for environmental impacts. The economic logic favors rapid deployment and market capture over comprehensive safety testing. PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), used in non-stick coatings, exemplifies this pattern: economically valuable, environmentally persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic. Only after decades of widespread use did comprehensive regulation begin.

Energy Systems and Climate Impacts

The global energy system represents the largest driver of climate change, the ultimate ecosystem impact of economic activity. Fossil fuels remain economically dominant because their prices exclude climate and pollution costs. Burning one barrel of oil generates approximately $30 in climate damage, yet this cost never appears on energy bills. This massive subsidy—economists estimate global fossil fuel subsidies at $7 trillion annually when including environmental costs—distorts energy markets fundamentally.

Renewable energy costs have plummeted, now competing economically with fossil fuels in most markets. Yet fossil fuels maintain dominance due to infrastructure lock-in, political influence, and existing subsidies. The economic incentive structure favors incumbent energy systems despite their ecological devastation. Transitioning toward renewable energy for homes and industrial applications requires overcoming entrenched economic interests and infrastructure.

Climate impacts themselves demonstrate economy-ecosystem feedback loops. Rising temperatures increase agricultural losses, property damage, health costs, and supply chain disruptions. The economic cost of unmitigated climate change could reach $23 trillion by 2050, far exceeding mitigation costs. Yet current economic systems discount future costs, making immediate emissions reduction economically undervalued. This temporal mismatch—where present economic incentives conflict with future ecological necessity—represents a structural problem in market-based systems.

Fisheries Economics and Marine Ecosystem Collapse

Global fisheries demonstrate how economic incentives can drive ecosystem collapse despite clear warning signs. Industrial fishing technology—sonar detection, GPS navigation, massive vessels, synthetic nets—enables unprecedented catch rates. Economically, this maximizes short-term revenue and profit. Ecologically, it exceeds sustainable yields by approximately 90%, meaning most fish stocks are harvested faster than they can reproduce.

Approximately 35% of global fish stocks are overfished, 60% are maximally exploited, and only 5% have recovery potential. This pattern results directly from economic incentives: individual fishing operators capture all revenue from each catch but bear none of the cost of depleted stocks. This classic tragedy of the commons creates systematic overharvesting. Economic theory predicts this outcome; market solutions have repeatedly failed to prevent it.

Subsidies amplify the problem. Governments provide approximately $35 billion annually in fishing subsidies, mostly enabling overfishing. From an economic perspective, these subsidies make unprofitable fishing viable, allowing operators to persist despite depleting stocks. From an ecological perspective, they accelerate collapse. Bycatch—killing non-target species—generates no revenue yet causes immense ecological damage, exemplifying how market values misalign with ecological reality.

Coral reef degradation illustrates cascading ecosystem impacts. Reefs support approximately 25% of marine species despite occupying 0.1% of ocean area. Economic activities—fishing, tourism, coastal development, climate change—damage reefs, reducing biodiversity and fishery productivity. The economic value of reef ecosystem services ($375 billion annually) far exceeds short-term extraction value, yet economic incentives favor immediate exploitation over long-term sustainability.

Urban Development and Habitat Fragmentation

Urbanization represents the fastest-growing land use change globally, with urban area expanding at 2-3% annually. Cities generate substantial economic value, concentrating human capital, infrastructure, and markets. Yet urban expansion fragments habitats, isolates populations, and reduces connectivity essential for ecosystem function. The economic incentives favor urban sprawl: land development generates profits, property values increase, and infrastructure expansion stimulates economic activity.

However, these benefits are often temporary and localized. Urban expansion increases infrastructure costs (roads, utilities, services), reduces agricultural productivity, and fragments ecosystems. Sprawling development patterns require greater energy for transportation, generating emissions and climate impacts. Dense urban development could reduce per-capita resource consumption and emissions by 50-80% compared to sprawl, yet economic incentives often favor sprawl because land is cheaper and development regulations less stringent.

Green infrastructure represents an attempt to integrate ecological function into urban economics. Parks, green roofs, restored wetlands, and urban forests provide ecosystem services—stormwater management, cooling, air purification, biodiversity habitat—while improving quality of life. Yet these investments compete with conventional development in capital allocation decisions. Economic valuation of ecosystem services helps justify green infrastructure, though it remains underutilized relative to potential.

Pathways to Economic-Ecological Integration

Addressing economy-ecosystem misalignment requires systemic changes across multiple levels. Carbon pricing mechanisms—whether taxes or cap-and-trade systems—attempt to internalize climate costs, though current prices remain far below true climate damage costs. Biodiversity offset programs aim to compensate for habitat loss, though they frequently fail to achieve genuine ecological equivalence. Payment for ecosystem services programs compensate communities for conservation, yet funding remains limited relative to conversion incentives.

Regenerative agriculture offers economic-ecological integration at the production level. By building soil health, enhancing biodiversity, and reducing input costs, regenerative approaches can improve long-term profitability while restoring ecosystem function. Yet transitional costs and market premiums remain barriers to widespread adoption. Policy support—subsidy redirection, research investment, market development—could accelerate transition.

Circular economy principles—designing out waste, extending product lifespans, recovering materials—reduce resource extraction and pollution while potentially improving profitability. Companies implementing circular models often discover efficiency gains exceeding transition costs. Yet systemic adoption requires overcoming infrastructure lock-in, consumer behavior patterns, and incumbent opposition.

Natural capital accounting integrates ecosystem values into national accounting systems, revealing how environmental degradation reduces genuine economic progress. Countries including Costa Rica, India, and Botswana have pioneered natural capital accounting, often discovering that conventional GDP growth masks ecological decline. Mainstreaming these approaches could fundamentally reorient economic policy toward sustainability.

The Ecorise Daily Blog provides ongoing analysis of these transitions, while academic research in Ecological Economics journals documents emerging frameworks for integration. International frameworks including the UN Sustainable Development Goals provide policy guidance, though implementation remains inconsistent.

FAQ

How much of global GDP depends on ecosystem services?

Research estimates that 50% of global GDP depends directly or indirectly on ecosystem services including pollination, water purification, climate regulation, and nutrient cycling. This dependency means economic collapse and ecological collapse are deeply connected.

What is an externality in environmental economics?

An externality occurs when economic activities create costs or benefits not reflected in market prices. Environmental externalities—pollution, habitat loss, climate change—represent enormous costs borne by society and ecosystems rather than polluters, distorting market incentives toward overexploitation.

Can economic growth and ecosystem restoration occur simultaneously?

Yes, but not with current consumption and production patterns. Decoupling economic growth from resource consumption and environmental impact requires circular economy transitions, renewable energy adoption, regenerative agriculture, and service-based rather than product-based economic models.

Why don’t markets automatically prevent ecosystem collapse?

Markets fail to prevent ecological collapse because ecosystem damage is externalized (costs borne by society rather than polluters), ecosystems lack property rights (making their degradation economically invisible), and market discounting undervalues future ecological services relative to present extraction.

What are the most promising policy solutions for economy-ecosystem integration?

Carbon pricing, natural capital accounting, subsidy redirection, regenerative agriculture support, circular economy incentives, and ecosystem service payments show promise. However, effectiveness requires political will to overcome incumbent interests and consumer behavior change toward sustainability.