Human Impact on Ecosystems: A Scientist’s View

The relationship between humanity and Earth’s ecosystems has fundamentally transformed over the past two centuries. What once represented a delicate balance of natural cycles and limited human intervention has evolved into a complex system where human activities are the dominant force shaping planetary health. From the Amazon rainforest to coral reef systems, from atmospheric composition to soil degradation, the evidence is unequivocal: human civilization has become the primary architect of ecological change on a global scale.

This transformation accelerated dramatically during the Industrial Revolution and has intensified exponentially with population growth, technological advancement, and consumption patterns. Scientists across multiple disciplines—from ecology and climate science to environmental economics—have documented unprecedented rates of species extinction, habitat loss, and ecosystem degradation. Yet understanding these impacts requires moving beyond simple cause-and-effect narratives to examine the complex interdependencies between economic systems, human behavior, and natural processes.

The scientific consensus reveals that current human activities are reshaping ecosystems at rates not seen since the last mass extinction event 66 million years ago. This article examines the multifaceted dimensions of human-ecosystem interactions, exploring the mechanisms of impact, the cascading consequences, and the pathways toward more sustainable relationships with the natural world.

Mechanisms of Ecological Disruption

Human impact on ecosystems operates through several interconnected mechanisms. The primary drivers include habitat destruction, overexploitation of resources, pollution, invasive species introduction, and climate modification. These mechanisms rarely operate in isolation; instead, they interact synergistically, amplifying their collective impact on ecosystem function and resilience.

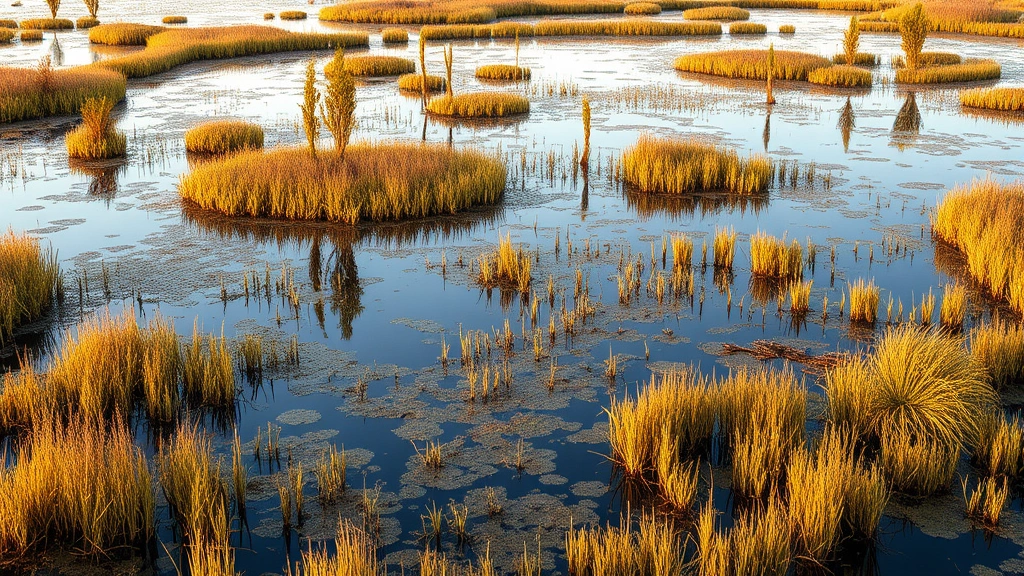

Habitat destruction represents the most direct and visible mechanism of ecological disruption. When forests are cleared for agriculture, wetlands are drained for development, or grasslands are converted to urban areas, the physical structure that supports entire communities of organisms disappears. This fragmentation isolates populations, reduces genetic diversity, and disrupts ecological processes like nutrient cycling and pollination. Research from conservation biology demonstrates that habitat loss accounts for approximately 73% of global species extinctions, making it the dominant driver of biodiversity decline.

Overexploitation occurs when human harvesting exceeds the reproductive capacity of populations. Fisheries worldwide exemplify this dynamic: industrial fishing removes biomass faster than populations can regenerate, fundamentally altering marine food webs. The relationship between agriculture and environmental management similarly shows how intensive farming depletes soil nutrients and groundwater reserves. When resource extraction rates exceed natural regeneration rates, ecosystems transition from productive to degraded states.

The introduction of invasive species represents another critical disruption mechanism. Non-native organisms introduced through trade, transportation, or human settlement can outcompete native species, consume native prey without natural predators, or introduce novel diseases. The zebra mussel in North American freshwater systems, cane toads in Australia, and kudzu in southeastern United States demonstrate how invasive species can restructure entire ecosystems within decades.

Biodiversity Loss and Species Extinction

Biodiversity—the variety of life at genetic, species, and ecosystem levels—underpins ecosystem stability and function. Current extinction rates far exceed background rates observed in the fossil record. Scientists estimate we are losing species at 100 to 1,000 times the natural extinction rate, a phenomenon some researchers term the “sixth mass extinction.”

This biodiversity loss manifests across multiple scales. At the genetic level, populations with reduced numbers experience inbreeding depression and loss of adaptive potential. Species-level extinctions eliminate unique evolutionary lineages and the ecological functions they perform. At the ecosystem level, reduced biodiversity decreases ecosystem resilience—the capacity to maintain function following disturbance—and reduces the range of ecosystem services available to human societies.

The drivers of biodiversity loss interconnect with broader patterns of human-environment interaction. Habitat conversion for agriculture affects 50% of Earth’s land surface. Climate change alters the environmental conditions species have adapted to over evolutionary time. Pollution introduces toxins that bioaccumulate through food chains. Overexploitation removes keystone species whose ecological roles are disproportionate to their abundance. The combination of these stressors creates conditions where many species cannot persist.

Tropical regions harbor the greatest species richness, yet face the most intense human pressures. Deforestation in the Amazon, Southeast Asian rainforests, and Central African Congo Basin threatens millions of species with extinction before they are even scientifically described. This represents not merely an aesthetic or ethical loss, but the elimination of biological solutions to survival challenges developed over millions of years of evolution.

Climate Change as Ecosystem Catalyst

Climate change represents a pervasive modifier of all other ecosystem impacts. By altering temperature regimes, precipitation patterns, and seasonal timing, climate change reshapes the fundamental conditions ecosystems evolved under. Unlike localized habitat destruction, climate change operates globally and simultaneously, leaving organisms no geographic refuge.

Warming temperatures trigger range shifts as species migrate toward cooler regions or higher elevations. This creates novel species combinations with unpredictable ecological consequences. Phenological mismatches occur when species that depend on each other—like flowering plants and their pollinators—respond to climate cues at different rates, disrupting the synchronization essential for their interactions. Rising sea levels inundate coastal wetlands and island ecosystems. Ocean acidification—caused by increased CO2 absorption—dissolves the calcium carbonate shells of marine organisms from pteropods to corals.

The mechanisms linking human activities to climate change operate through the carbon cycle. Burning fossil fuels, clearing forests, and agricultural intensification release carbon dioxide and methane—potent greenhouse gases. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased 50% since pre-industrial times, from 280 to over 420 parts per million, a rate of change unprecedented in at least 800,000 years. This rapid change prevents natural adaptation and pushes climate systems toward new equilibrium states with unknown characteristics.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, climate impacts on ecosystems are already substantial and will intensify dramatically even with aggressive emissions reductions. Coral reef bleaching events, triggered by warming ocean temperatures, have become nearly annual occurrences in many regions. Arctic ecosystems face transformation as sea ice disappears and permafrost thaws, releasing additional carbon. Mountain ecosystems experience species range compression as suitable habitat is squeezed between warming lowlands and immobile summits.

Pollution and Chemical Contamination

Chemical pollution represents an insidious ecosystem stressor operating at scales from local to global. Persistent organic pollutants—compounds that resist environmental breakdown—accumulate in organisms and concentrate through food chains, reaching toxic levels in top predators despite low environmental concentrations. Microplastics, fragments of synthetic polymers smaller than 5 millimeters, now contaminate every ecosystem from deep ocean trenches to Arctic ice and have been detected in human blood and lung tissue.

Nutrient pollution—excess nitrogen and phosphorus from agricultural runoff and wastewater—triggers eutrophication cascades. Algal blooms consume oxygen, creating “dead zones” where most aquatic life cannot survive. The Gulf of Mexico dead zone, created primarily by Mississippi River nitrogen loading from Midwestern agriculture, covers thousands of square kilometers annually. Similar hypoxic zones now exist in hundreds of coastal systems worldwide.

Heavy metals like mercury, lead, and cadmium enter ecosystems through industrial emissions, mining, and combustion. These persist indefinitely, accumulate in organisms, and cause neurological and developmental damage even at low concentrations. Mercury methylation in aquatic systems creates especially toxic forms that bioaccumulate to dangerous levels in fish, affecting both wildlife and human consumers.

Pesticide use, essential to modern agriculture, also creates ecosystem damage. Neonicotinoid insecticides, designed to target insect nervous systems, affect non-target organisms including pollinators crucial for food production. Their systemic nature means they persist in soil and water, creating chronic exposure. Herbicide use selects for resistant weeds while eliminating the diverse plant communities that support insect and bird populations.

Economic Systems and Ecosystem Services

Understanding human impact on ecosystems requires examining the economic structures driving resource extraction and ecosystem conversion. Ecological economics—an interdisciplinary field examining the relationships between economies and ecosystems—reveals that conventional economic systems systematically undervalue ecosystem services and overexploit natural capital.

Ecosystem services—the benefits humans derive from ecosystems—include provisioning services like food and water, regulating services like climate stabilization and flood control, supporting services like nutrient cycling, and cultural services like recreation and spiritual fulfillment. Yet standard economic accounting systems assign zero value to these services until they are lost or degraded. A forest provides timber value when harvested but receives no economic credit for carbon sequestration, water filtration, or habitat provision while standing.

This valuation gap creates perverse incentives favoring short-term exploitation over long-term sustainability. Economic actors rationally choose to convert forests to pasture or cropland because the immediate economic returns exceed the discounted future value of ecosystem services. When ecosystem service values are incorporated into economic analysis—a practice increasingly adopted by forward-thinking organizations—the economic case for conservation becomes compelling. Research from the World Bank demonstrates that ecosystem conservation often generates greater long-term economic value than conversion.

The relationship between consumption patterns and ecosystem impact operates through supply chains often invisible to consumers. Sustainable fashion requires understanding that clothing production impacts water systems, soil health, and biodiversity. Similarly, reducing carbon footprint demands recognizing how energy use, transportation, and consumption patterns cascade through ecosystems. Economic systems that fail to price ecological externalities—costs borne by society rather than market actors—systematically generate unsustainable outcomes.

Tipping Points and Irreversible Changes

Ecosystems possess resilience—the capacity to return to previous states following disturbance—but this resilience has limits. When disturbances exceed critical thresholds, ecosystems can shift abruptly to alternative stable states with different species compositions, functions, and services. These tipping points represent potential points of no return in ecosystem degradation.

The Amazon rainforest exemplifies this concern. Deforestation combined with climate change may push the system past a threshold where it transitions from forest to savanna. This shift would be catastrophic: forests currently provide moisture that falls as rain across South America, supporting agriculture throughout the continent. Loss of this moisture recycling would cause cascading agricultural failures across multiple countries. The forest’s carbon storage would convert to carbon emission, accelerating climate change globally. Once past this threshold, ecosystem recovery might be impossible on human timescales.

Coral reef systems face similar tipping point risks. Warming oceans cause coral bleaching—expulsion of symbiotic algae—which leads to coral death if temperatures don’t cool quickly. Acidification impairs coral skeleton formation. Overfishing removes herbivorous fish that control algae, allowing algae to outcompete recovering corals. Once algae-dominated, reefs resist recovery even if individual stressors are reduced. Scientists estimate that if warming exceeds 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, 70-90% of coral reefs will be lost, with functional extinction of reef ecosystems at 2°C warming.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation—ocean currents including the Gulf Stream—faces potential collapse if freshwater from melting Greenland ice dilutes surface waters and reduces density-driven circulation. This would fundamentally alter climate patterns across the Northern Hemisphere and disrupt fisheries supporting millions of people. Arctic permafrost thaw releases methane and CO2, creating positive feedback loops that accelerate warming. These tipping points are not distant theoretical concerns; current trajectories suggest some may be approached within decades.

Pathways to Ecological Recovery

Understanding human impact on ecosystems is not merely an exercise in documenting decline; it provides foundation for identifying recovery pathways. Ecological restoration—active efforts to rebuild ecosystem structure and function—demonstrates that degraded systems can recover when given opportunity and support. However, recovery often requires decades or centuries and may not restore ecosystems to pre-disturbance states.

Effective recovery strategies operate at multiple scales. Local efforts include habitat restoration, invasive species removal, and pollution cleanup. Regional strategies involve establishing protected area networks that maintain habitat connectivity and allow species movement. Global initiatives address climate change and international pollutants. The most effective approaches integrate these scales while considering renewable energy transitions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions driving ecosystem change.

Nature-based solutions—strategies that leverage ecosystem processes for human benefit—offer particular promise. Wetland restoration provides flood control and water filtration while restoring habitat. Mangrove protection and restoration sequester carbon while supporting fisheries. Reforestation sequesters carbon while restoring habitat connectivity. These approaches generate multiple co-benefits, making them economically attractive even without considering intrinsic ecological value.

Transforming economic systems toward sustainability requires fundamental shifts in how societies value nature. Circular economy principles minimize resource extraction and waste by keeping materials in use cycles. Regenerative agriculture rebuilds soil health and biodiversity while producing food. Renewable energy eliminates fossil fuel combustion, the dominant driver of climate change. These transitions require policy support, technological innovation, and consumer behavior change—challenging but increasingly recognized as necessary.

Scientific research continues revealing how ecosystems function and respond to human activities, providing essential knowledge for recovery efforts. Understanding trophic cascades—how changes in top predators cascade through food webs—has guided successful reintroduction programs. Comprehending mycorrhizal networks—fungal connections linking trees underground—has transformed forest restoration practices. Recognizing the role of disturbance in maintaining diversity has shifted conservation from preservation toward active management.

FAQ

What is the primary driver of species extinction?

Habitat destruction accounts for approximately 73% of documented species extinctions. When ecosystems are converted to human uses—agriculture, urban development, resource extraction—the organisms inhabiting them lose essential survival requirements. This remains the dominant extinction driver globally, though climate change, pollution, and overexploitation contribute significantly.

How quickly are species being lost compared to natural rates?

Current extinction rates are estimated at 100 to 1,000 times background rates observed in the fossil record. This acceleration qualifies as a mass extinction event. While natural extinctions occur constantly as part of evolutionary processes, current rates far exceed evolutionary replacement rates, causing net biodiversity decline.

Can ecosystems recover from human damage?

Many ecosystems can recover if given sufficient time and reduced human pressure. Forests regenerate when logging ceases, fish populations rebuild when fishing stops, and water quality improves when pollution sources are eliminated. However, recovery timescales are often measured in decades or centuries, and some changes—particularly those approaching ecosystem tipping points—may be irreversible on human timescales.

What is the relationship between economic systems and ecosystem damage?

Conventional economic systems fail to price ecosystem services, creating incentives for unsustainable resource extraction. When ecosystem values are incorporated into economic analysis, conservation often becomes economically optimal. Transforming toward circular economies, regenerative agriculture, and renewable energy reduces human impact while potentially improving long-term economic outcomes.

Are climate tipping points inevitable?

Some tipping points may be unavoidable given current atmospheric CO2 levels and warming already committed by past emissions. However, aggressive emissions reductions can prevent additional tipping points and reduce the severity of changes already triggered. The difference between 1.5°C, 2°C, and 3°C warming represents dramatically different ecosystem outcomes and human impacts.

What can individuals do to reduce their ecosystem impact?

Individual actions include reducing consumption, supporting sustainable products, adopting renewable energy where possible, and advocating for policy changes. While individual actions are important for awareness and norm-shifting, systemic change requires policy support and economic transformation. Both individual responsibility and systemic change are necessary for ecological recovery.