Impact of Economy on Ecosystems: Study Insights

The intricate relationship between economic systems and ecological health represents one of the most pressing challenges of our time. Economic activities—from industrial production to agricultural expansion—fundamentally reshape natural environments, often with cascading consequences that extend far beyond initial extraction or development zones. Recent research demonstrates that the global economy’s trajectory remains largely disconnected from planetary boundaries, creating a widening chasm between economic growth metrics and ecosystem resilience.

Understanding this dynamic requires examining how financial incentives, market structures, and policy frameworks either accelerate ecological degradation or foster regeneration. The economy’s impact on ecosystems manifests through multiple pathways: resource depletion, pollution generation, habitat fragmentation, and climate forcing. Simultaneously, ecosystem services—the natural processes that support all economic activity—continue declining as economic expansion prioritizes short-term gains over long-term ecological stability.

Economic Growth and Ecological Degradation

Conventional economic models measure progress through Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a metric that captures market transactions without accounting for natural capital depletion or environmental externalities. This fundamental accounting error creates perverse incentives where ecosystem destruction registers as economic gain. A forest clearance for timber production increases GDP while simultaneously reducing biodiversity, carbon sequestration capacity, and watershed regulation services.

Research from the World Bank indicates that if natural capital depreciation were incorporated into national accounting systems, many countries would show negative net economic growth. The disconnect between economic indicators and ecological reality has intensified over recent decades, with global biodiversity indices declining by approximately 70% since 1970 while world GDP expanded threefold.

The definition of environment and environmental science increasingly emphasizes systemic thinking that recognizes economic activity as embedded within ecological systems rather than external to them. Traditional neoclassical economics treats nature as an unlimited resource pool and waste sink, assumptions that no longer reflect planetary realities.

Decoupling economic growth from resource consumption remains theoretically possible but practically elusive. Relative decoupling—where resource intensity per unit GDP decreases while absolute consumption continues rising—has characterized wealthy nations’ development patterns. Absolute decoupling, where total resource consumption declines while economies expand, remains rare and geographically limited. This distinction matters profoundly for understanding whether current economic trajectories can achieve sustainability.

Resource Extraction and Habitat Loss

The economy’s appetite for raw materials drives unprecedented habitat conversion and species extinction. Mining operations, logging concessions, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development collectively eliminate or degrade ecosystems at rates exceeding natural regeneration capacities. The Amazon rainforest, which generates roughly 20% of global oxygen while sequestering vast carbon reserves, faces accelerating deforestation driven by cattle ranching and soy cultivation—both economically incentivized by global commodity markets.

Extractive industries generate significant GDP contributions while externalizing ecological costs. A single large-scale mining operation might contribute millions to regional economies while permanently degrading watersheds, contaminating soils, and displacing indigenous communities whose livelihoods depend on intact ecosystems. The environment examples of resource-dependent regions illustrate how short-term economic gains translate into long-term ecological and social costs.

Overfishing exemplifies resource extraction dynamics. Industrial fishing fleets, economically optimized for maximum catch volumes, have depleted major fish stocks to commercial extinction levels. The economic logic driving this outcome—where individual operators benefit from extraction while costs distribute across society—creates tragedy-of-the-commons scenarios. Fish populations cannot regenerate when harvest rates exceed reproductive capacity, yet individual economic incentives push operators toward maximum extraction regardless of sustainability.

Agricultural expansion represents the single largest driver of habitat loss globally. Converting forests, wetlands, and grasslands to cropland or pasture eliminates specialized species while fragmenting remaining habitats into isolated patches insufficient to maintain viable populations. Monoculture agriculture, economically efficient for commodity production, replaces biodiverse ecosystems with simplified systems vulnerable to pest outbreaks and climatic variability.

Pollution Pathways: From Economy to Ecosystems

Economic production generates pollution as an inherent byproduct, with disposal into environmental media (air, water, soil) treated as a free service. Manufacturing processes, energy production, transportation, and chemical synthesis all generate emissions and waste streams that degrade ecosystem function. Industrial agriculture contributes nitrogen and phosphorus runoff that creates oceanic dead zones, while plastic production—economically profitable but ecologically catastrophic—generates persistent pollution across all environmental compartments.

The economic incentive structure encourages pollution generation because waste disposal costs nothing when environmental media absorb pollutants without compensation. A factory operator rationally chooses to discharge untreated effluent into rivers rather than invest in treatment systems, capturing private benefits while society bears pollution costs. This disconnect between private profit and social cost represents a fundamental market failure that standard economic analysis rarely addresses adequately.

Heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, and microplastics accumulate in food webs, biomagnifying as they move through trophic levels. Apex predators and humans consuming contaminated prey face exposure to toxicant concentrations millions of times higher than environmental levels. Economic activities generating these pollutants rarely internalize health costs, making pollution-intensive production artificially profitable.

Atmospheric pollution from fossil fuel combustion represents perhaps the most consequential pollution pathway. Carbon dioxide emissions from economic activity drive climate change, while particulate matter and nitrogen oxides create localized air quality crises affecting billions globally. The economic system’s reliance on carbon-intensive energy sources reflects historical accident and infrastructure lock-in rather than efficiency—renewable energy now costs less than fossil fuels in most contexts, yet economic structures and subsidies continue favoring carbon-intensive production.

Climate Economics and Ecosystem Collapse

Climate change, fundamentally driven by economic activity, represents the most systemic threat to ecosystem stability. Rising temperatures alter precipitation patterns, extend growing seasons unevenly, shift species ranges, and increase extreme weather frequency. Ecosystems adapted to historical climate conditions face novel conditions exceeding their tolerance ranges, triggering cascade failures across interdependent species and functions.

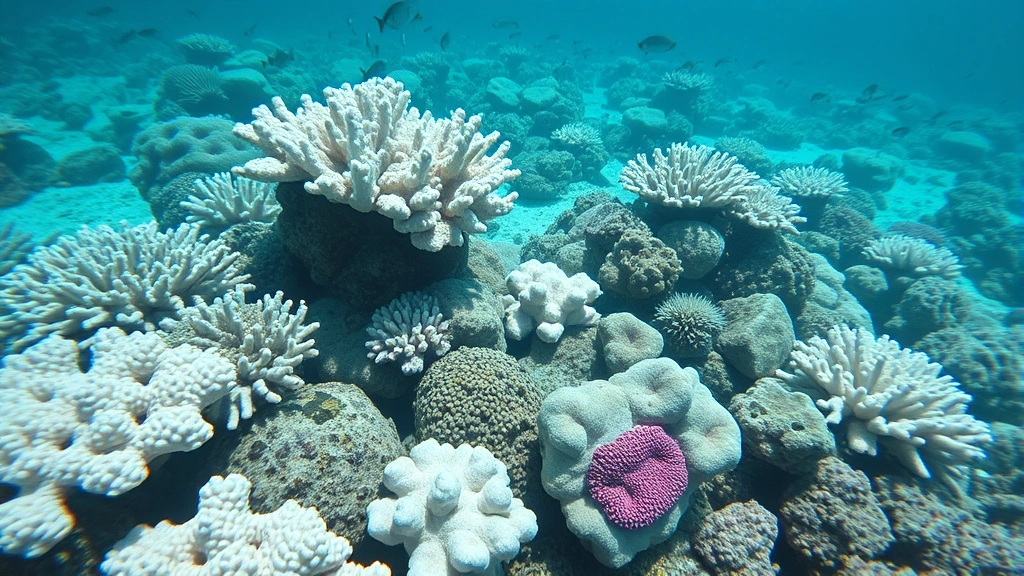

Coral reef ecosystems exemplify climate-driven ecosystem collapse. Warming oceans stress corals, triggering bleaching events where symbionts are expelled and reefs lose their primary productivity source. Economically valuable fisheries depending on reef habitat collapse alongside the reefs themselves, yet the economic system generating climate forcing lacks mechanisms to prevent this destruction. UNEP research indicates that coral reef economic value exceeds $375 billion annually, yet climate change threatens these ecosystems with near-total loss within decades if current trajectories continue.

The economic cost of climate change mitigation pales beside adaptation and damage costs if warming continues unchecked. Investing in renewable energy and ecosystem restoration now costs far less than managing climate refugees, agricultural collapse, and infrastructure destruction later. Yet economic decision-making structures discount future costs heavily, making present sacrifice for future benefit economically irrational under conventional frameworks.

Climate impacts disproportionately affect nations and communities least responsible for emissions, creating profound equity dimensions. Low-income countries dependent on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture and fishing face existential threats from climate change driven by wealthy nations’ consumption patterns. This inequity undermines both ecological and social stability, as climate migration and resource conflicts intensify.

Valuing Ecosystem Services

Ecosystems provide services essential to human survival and economic activity: pollination, water purification, climate regulation, soil formation, nutrient cycling, and pest control, among others. These services have no market price, making them economically invisible despite their irreplaceable value. Quantifying ecosystem services in monetary terms helps demonstrate their economic importance and justify conservation investment.

Pollination services provided by wild bees, butterflies, and other insects globally exceed $15 billion annually in crop value. Yet economic activity destroying pollinator habitat through pesticide use and monoculture agriculture continues expanding because the ecosystem service value doesn’t appear on balance sheets. Internalizing pollination service value into agricultural economics would dramatically shift production methods toward pollinator-friendly approaches.

Water purification by wetlands and forests eliminates the need for expensive treatment infrastructure while improving water quality. Protecting intact ecosystems providing these services costs far less than building treatment facilities to replace them. Yet wetlands are drained for development and forests cleared for agriculture because real estate development generates immediate economic returns while ecosystem service values remain uncounted.

Mangrove forests provide nursery habitat for commercially valuable fish species, storm surge protection for coastal communities, and carbon sequestration. Economic valuation studies assign mangrove ecosystem services values exceeding $100,000 per hectare over their lifetime. Despite this enormous value, mangroves are cleared for aquaculture and coastal development because aquaculture companies capture immediate profits while society loses ecosystem service value.

Carbon sequestration by forests, wetlands, and soils represents perhaps the most critical ecosystem service given climate change urgency. Protecting and restoring these carbon-storing ecosystems costs far less than technological carbon removal approaches, yet economic structures incentivize conversion to carbon-releasing land uses. How to reduce carbon footprint strategies increasingly emphasize ecosystem protection and restoration as cost-effective climate solutions.

Regenerative Economic Models

Emerging economic frameworks attempt to realign economic activity with ecological constraints and regenerative principles. Circular economy models emphasize material cycling, waste elimination, and product longevity rather than linear extraction-production-disposal patterns. Regenerative agriculture rebuilds soil health, increases carbon sequestration, and enhances biodiversity while maintaining productivity. Doughnut economics proposes balancing human needs within planetary boundaries rather than pursuing unlimited growth.

These alternative frameworks share recognition that ecological systems possess finite regenerative capacity and that economic activity must operate within these limits. Rather than treating nature as external resource pool, regenerative models embed economics within ecological systems, measuring success by ecosystem health alongside human wellbeing.

Renewable energy for homes represents one practical manifestation of regenerative principles, replacing fossil fuel dependence with clean energy systems that eliminate carbon emissions while reducing household economic vulnerability. Similar regenerative approaches across agriculture, manufacturing, and commerce demonstrate that economic viability and ecological regeneration need not conflict.

Regenerative models require fundamental shifts in how societies measure economic success. GDP replacement with wellbeing indices incorporating ecological health, social equity, and human flourishing would reorient economic incentives toward sustainable pathways. Several nations have begun implementing alternative metrics, with New Zealand and Scotland formally adopting wellbeing frameworks for policy decisions.

The economic transition toward regenerative models faces substantial resistance from incumbent interests benefiting from current arrangements. Fossil fuel companies, industrial agriculture conglomerates, and extractive industries possess enormous political influence and financial resources to prevent policy shifts threatening their business models. Overcoming this resistance requires building political coalitions prioritizing long-term ecological stability over short-term corporate profits.

Policy Mechanisms and Market Interventions

Governments possess multiple policy tools to align economic activity with ecological sustainability. Carbon pricing mechanisms—either carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems—internalize climate costs into fossil fuel prices, making clean energy economically competitive. Removing fossil fuel subsidies, which exceed $7 trillion annually when accounting for environmental costs, would dramatically accelerate renewable energy adoption.

Payments for ecosystem services directly compensate landowners for maintaining ecosystems providing services. Forest conservation payments, wetland protection programs, and agricultural subsidies supporting soil health align economic incentives with ecological benefits. These programs remain underfunded relative to subsidies supporting destructive practices, but they demonstrate feasibility of market-based conservation approaches.

Regulatory approaches including protected area networks, pollution limits, and sustainable harvest regulations constrain economically destructive activities. While less economically efficient than perfectly designed market mechanisms, regulations provide certainty and prevent races-to-the-bottom where jurisdictions compete by loosening environmental standards. Combining regulatory baselines with market mechanisms yields more robust outcomes than either approach alone.

Extended producer responsibility policies require manufacturers to manage products’ end-of-life disposal, internalizing waste management costs into production decisions. This policy approach encourages design for durability and recyclability, reducing material extraction and waste generation. The sustainable fashion brands comprehensive guide illustrates how extended responsibility drives industry transformation toward circular economy models.

International agreements including the Paris Climate Accord, Convention on Biological Diversity, and emerging nature-focused treaties attempt coordinating global responses to transboundary ecological challenges. These frameworks remain inadequately ambitious and poorly enforced, but they establish principles that economic activity must respect planetary boundaries and support ecosystem restoration.

The Ecorise Daily blog regularly covers policy developments and economic innovations advancing ecological sustainability, providing current analysis of how economic systems are adapting to ecological realities. Tracking these developments reveals both progress toward regenerative economics and persistent barriers to transformation.

FAQ

How does economic growth harm ecosystems?

Economic growth typically increases resource extraction, pollution generation, and habitat conversion rates. Standard GDP metrics don’t account for natural capital depletion, making environmentally destructive activities appear economically beneficial. This misalignment between economic incentives and ecological outcomes drives systematic ecosystem degradation.

Can economic systems become truly sustainable?

Yes, but only through fundamental restructuring prioritizing ecological limits over unlimited growth. Regenerative economic models demonstrate that human wellbeing can improve within planetary boundaries. However, this transition requires political will to challenge incumbent interests and restructure financial systems toward long-term sustainability.

What role do consumers play in ecosystem impacts?

Consumer choices drive demand for products, but individual consumption changes alone cannot address systemic economic drivers of ecosystem destruction. Systemic change requires policy intervention, corporate accountability, and economic restructuring. Consumer awareness supports these changes by building political constituencies for transformation.

How are ecosystem services valued economically?

Economists use multiple valuation approaches including market prices for ecosystem products, replacement cost analysis comparing ecosystem services to technological alternatives, and contingent valuation assessing willingness-to-pay for ecosystem protection. These valuations demonstrate ecosystem services’ enormous economic importance, often exceeding hundreds of billions annually.

What economic policies most effectively protect ecosystems?

Combining carbon pricing with fossil fuel subsidy elimination, protected area networks, sustainable harvest regulations, and payments for ecosystem services yields more effective results than individual policies alone. International coordination prevents jurisdictional competition in loosening environmental standards, strengthening policy effectiveness.

How do regenerative economic models differ from sustainable economics?

Sustainable economics seeks to maintain current conditions indefinitely, while regenerative economics aims to restore degraded ecosystems and improve ecological health. Regenerative approaches recognize that previous economic activity has damaged ecosystems requiring active restoration, not merely preservation of current degraded conditions.