Natural Gas Impact on Ecosystems: Expert Insight

Natural gas has emerged as a transitional energy source in global energy portfolios, often promoted as a cleaner alternative to coal and oil. However, the extraction, processing, transportation, and combustion of natural gas present complex and multifaceted challenges to ecosystems worldwide. Understanding the effects of natural gas on environment requires examining the complete lifecycle of this fossil fuel, from wellhead to end-user, and recognizing how its exploitation interconnects with broader environmental degradation patterns.

The relationship between natural gas development and ecosystem health reveals a paradox: while natural gas produces fewer carbon emissions than coal when burned for electricity, the methane leakage throughout its supply chain, combined with habitat destruction from extraction activities, creates significant ecological consequences. This comprehensive analysis explores the mechanisms through which natural gas impacts natural systems, the quantifiable environmental costs, and the implications for long-term ecosystem resilience and economic sustainability.

Methane Emissions and Climate Forcing

Methane represents the primary environmental concern associated with natural gas production and distribution. While carbon dioxide receives greater attention in climate discussions, methane possesses a global warming potential approximately 28-34 times greater than CO₂ over a 100-year timeframe, and up to 80-86 times greater over 20 years, according to recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessments. This distinction becomes crucial when evaluating natural gas’s role as a climate solution.

Methane leakage occurs at multiple stages within the natural gas supply chain. During extraction, unconventional drilling operations utilizing hydraulic fracturing release methane from geological formations. Processing facilities, where natural gas undergoes compression and purification, represent significant leak points. Transportation through extensive pipeline networks—spanning millions of kilometers globally—introduces fugitive emissions from compressor stations, valve failures, and pipeline corrosion. Distribution systems serving residential and commercial users contribute additional losses, with some urban systems losing 2-4% of throughput to leakage.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that methane emissions from natural gas operations constitute approximately 10% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. When considering the complete lifecycle, studies published in Nature and related peer-reviewed journals suggest that natural gas’s climate advantage over coal diminishes significantly when leakage rates exceed 3-4%. In regions with older infrastructure or inadequate maintenance protocols, actual leakage rates often approach or exceed these thresholds, fundamentally undermining the climate rationale for natural gas expansion.

The temporal dimension of methane forcing presents particular concern. Because methane’s warming impact concentrates in the near-term (20-year horizon), emissions from current natural gas infrastructure directly affect climate outcomes during the critical 2020-2040 period when scientists emphasize rapid emission reductions become essential for limiting warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This timing consideration challenges the narrative positioning natural gas as a bridge fuel toward renewable energy systems.

Habitat Destruction and Biodiversity Loss

Natural gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing and conventional drilling fundamentally alters terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems through landscape fragmentation and habitat conversion. Industrial drilling operations require extensive infrastructure development: wellpads, access roads, pipeline corridors, compressor stations, and processing facilities. This development pattern creates a patchwork of disturbed lands that interrupts wildlife movement corridors and fragments populations of sensitive species.

In North America’s shale gas regions—particularly the Marcellus, Eagle Ford, and Permian formations—extraction has transformed millions of acres of forest, prairie, and wetland ecosystems. Research documents significant declines in bird populations, particularly grassland and forest-interior species sensitive to habitat fragmentation. The Appalachian region’s natural gas boom correlates with documented population declines in cerulean warblers, Kentucky warblers, and other migratory species dependent on intact forest habitat.

Beyond direct habitat loss, natural gas development generates ecological edge effects. The clearing of vegetation around wells and infrastructure creates abrupt transitions between developed and natural areas, exposing interior species to increased predation, parasitism, and invasive species colonization. Light pollution from wellsite operations disrupts nocturnal wildlife behavior and breeding patterns. Noise from compressor stations and drilling equipment creates acoustic stress for species relying on sound for communication and predator detection.

Wetland ecosystems face particular vulnerability. Natural gas operations in wetland regions—common in the Gulf Coast, Arctic regions, and other productive ecosystems—result in direct wetland loss through wellpad construction and indirect impacts through altered hydrology. Pipeline construction through wetlands disrupts water flow patterns and soil structure, degrading these highly productive ecosystems that support disproportionate biodiversity and provide critical ecosystem services including water filtration and carbon storage.

The cumulative effect of these impacts reduces ecosystem resilience, limiting natural systems’ capacity to adapt to additional stressors including environmental science challenges and climate variability. Fragmented populations become increasingly vulnerable to local extinction, reducing genetic diversity and adaptive capacity within species populations.

Water Contamination and Hydrological Impacts

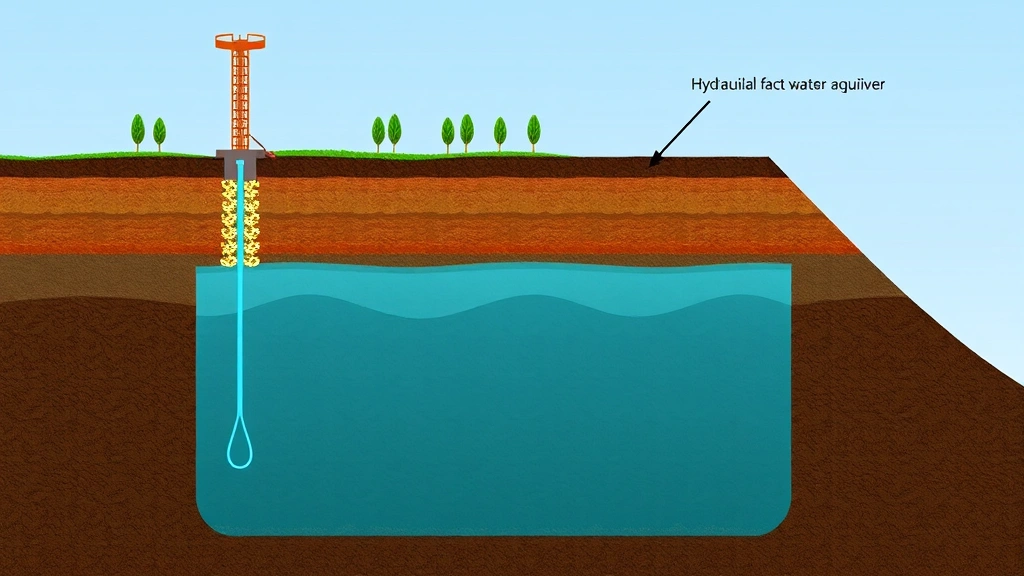

Water contamination represents one of the most concerning ecosystem impacts from natural gas extraction, particularly through hydraulic fracturing operations. The process involves injecting millions of gallons of water mixed with chemicals and proppants (typically sand) into geological formations under extreme pressure. This creates pathways for both intended fluid movement and unintended migration of contaminants.

Primary contamination pathways include: direct injection fluid migration through inadequate well casings reaching overlying aquifers; induced seismic activity fracturing natural geological barriers; and surface spills from operational activities. Injected fluids contain chemicals including benzene, toluene, xylene, and various additives, many classified as hazardous substances. Additionally, the fracturing process mobilizes naturally occurring contaminants including heavy metals, radioactive elements, and high-salinity brines that existed in target geological formations.

Documented cases of groundwater contamination near hydraulic fracturing operations have occurred across North America. In Pennsylvania’s Marcellus region, state regulators documented methane in residential water wells correlating spatially with nearby drilling operations. In Colorado and Wyoming, elevated uranium and radium concentrations appeared in wells downgradient from drilling sites. While operators dispute causation in individual cases, the spatial and temporal patterns strongly suggest drilling-related contamination.

Beyond direct chemical contamination, natural gas operations alter hydrological systems through water extraction for hydraulic fracturing. A single well may require 2-8 million gallons of water during its lifecycle. In water-scarce regions including Texas, Oklahoma, and parts of the Mountain West, this extraction competes with agricultural irrigation and municipal supplies. In the Permian Basin, natural gas operations extract water from the Pecos River, a critical ecosystem supporting endangered species and irrigating downstream agricultural lands.

Wastewater disposal from natural gas operations creates additional hydrological impacts. Produced water—formation fluids brought to the surface during extraction—contains high salinity and dissolved minerals. Deep injection of this wastewater has induced seismic activity in Oklahoma, Texas, and other regions, with earthquakes damaging infrastructure and potentially destabilizing geological formations. Surface discharge of produced water contaminates streams and groundwater, elevating salinity levels and harming aquatic organisms.

These water impacts directly undermine human-environment interactions in affected regions, compromising ecosystem services and creating conflicts between energy production and water security.

Air Quality Degradation

While natural gas combustion produces fewer particulate emissions than coal, the extraction and processing stages generate significant air pollutants affecting both local and regional air quality. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released during drilling and production operations contribute to ground-level ozone formation, particularly problematic in regions with high solar radiation and existing ozone challenges.

Natural gas operations emit nitrogen oxides (NOx), which combine with VOCs in atmospheric chemistry to generate ozone—a potent respiratory irritant and plant toxin. In the Upper Green River Basin of Wyoming, natural gas development coincided with ozone concentrations exceeding National Ambient Air Quality Standards, degrading air quality in previously pristine areas. Similar patterns emerged in the Uinta Basin of Utah and parts of the Permian Basin in Texas.

Diesel emissions from drilling equipment, compressor engines, and heavy truck traffic associated with natural gas operations contribute particulate matter and additional NOx. In communities adjacent to drilling operations, residents report elevated respiratory symptoms, particularly among children and elderly populations. While epidemiological studies remain limited, available evidence suggests increased asthma exacerbations and other respiratory impacts in proximity to active drilling sites.

Compressor stations—essential infrastructure for moving natural gas through pipelines—operate continuously and emit methane alongside other air pollutants. These facilities generate noise levels exceeding 80 decibels, documented to cause stress responses in humans and wildlife. In rural areas where compressor stations locate near residences, residents experience chronic noise exposure linked to sleep disruption, cardiovascular stress, and psychological effects.

Economic Externalities and True Cost Accounting

Conventional economic analysis of natural gas typically excludes environmental costs, a practice that misrepresents true economic efficiency. When ecosystem damages, health costs, and climate impacts receive monetization using established environmental economics methodologies, natural gas becomes substantially less competitive economically.

Ecological economics frameworks quantify ecosystem services—functions performed by natural systems providing human benefits. Wetland loss from natural gas development eliminates services including water filtration, flood storage, and wildlife habitat valued at $10,000-$100,000 per acre annually depending on ecosystem type. Forest fragmentation reduces carbon sequestration capacity and wildlife habitat services. Groundwater contamination imposes remediation costs, reduced property values, and health expenses.

Climate damages from methane emissions warrant particular attention. Using the social cost of carbon—an economic metric quantifying climate change damages per ton of CO₂ equivalent—methane emissions from natural gas operations impose external costs of $50-$200 per ton CO₂e depending on discount rate assumptions. For a typical natural gas power plant operating 40 years, lifecycle methane emissions create climate damages exceeding $2-8 billion, costs borne by society rather than energy producers.

Health costs from air quality degradation include respiratory disease treatment, lost productivity, and premature mortality. Research from the World Bank and UNEP quantifies air pollution costs at 4-6% of GDP in regions with significant natural gas operations. For natural gas-producing regions, these costs often represent $1-3 billion annually.

When comprehensive cost accounting includes environmental and health externalities, natural gas becomes economically inferior to renewable energy sources including wind and solar, which have achieved dramatic cost reductions over the past decade. This economic reality contradicts narratives positioning natural gas as a cost-effective transition fuel, revealing instead how market failures—the failure to price environmental costs—distort economic decision-making.

Understanding these economic dimensions connects to broader principles of environmental and natural resources management, where true cost accounting becomes essential for sustainable resource governance.

Regional Case Studies

Marcellus Shale Region (Appalachia): The Marcellus formation underlying Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and adjacent states represents North America’s largest natural gas reserve. Since 2008, over 8,000 wells have been drilled, transforming the region’s landscape. Documented impacts include methane contamination of water wells in Dimock, Pennsylvania; habitat fragmentation affecting migratory birds; and air quality degradation in rural communities. The region illustrates how natural gas development concentrates environmental impacts in economically disadvantaged areas, raising environmental justice concerns.

Permian Basin (Texas and New Mexico): This region produces approximately one-quarter of U.S. natural gas and experiences rapid expansion. Water stress represents the critical impact—natural gas operations compete with agricultural irrigation for limited Pecos River water. Induced seismic activity from wastewater injection has damaged infrastructure. Air quality degradation creates ozone exceedances in previously compliant areas. The region demonstrates how natural gas development exacerbates existing environmental stressors in water-limited ecosystems.

Arctic Natural Gas Development: Proposed and ongoing natural gas projects in Arctic regions—including Russia’s Yamal Peninsula and potential North American Arctic development—threaten pristine ecosystems supporting indigenous populations and unique wildlife. Permafrost thaw triggered by climate change and development activities releases additional methane, creating positive feedback loops amplifying warming. Arctic natural gas development represents particularly problematic expansion given the region’s climate sensitivity.

Mitigation Strategies and Alternatives

Addressing natural gas’s ecosystem impacts requires multi-pronged approaches ranging from operational improvements to fundamental energy system transformation. Mitigation strategies include:

- Methane leak reduction: Enhanced monitoring and repair of pipeline infrastructure, compressor station maintenance, and well integrity verification can reduce fugitive emissions by 40-60%. Technologies including infrared imaging and satellite-based methane detection enable cost-effective leak identification.

- Habitat protection: Establishing protected areas excluding natural gas development preserves ecosystem integrity. Strategic placement of infrastructure minimizing fragmentation reduces biodiversity impacts. Restoration of degraded habitats near development sites partially compensates for unavoidable losses.

- Water protection: Enhanced well casing standards, improved wastewater treatment and disposal protocols, and prohibition of operations in sensitive aquifer zones reduce water contamination risks. Recycling produced water for beneficial uses reduces both freshwater extraction and wastewater disposal impacts.

- Renewable energy acceleration: Rapid deployment of wind, solar, geothermal, and other renewable sources eliminates the need for natural gas expansion. Renewable energy for homes and grid-scale applications now achieves cost parity with natural gas while eliminating extraction-related ecosystem impacts.

- Energy efficiency: Improved building insulation, industrial process efficiency, and transportation electrification reduce overall energy demand, obviating natural gas infrastructure expansion. Strategies to reduce carbon footprint frequently emphasize efficiency as the most cost-effective climate solution.

- Carbon pricing: Implementing carbon prices reflecting true climate costs makes renewable energy economically superior to natural gas, driving market-based transition toward clean energy.

Most effective mitigation requires combining these strategies—no single approach adequately addresses the full spectrum of natural gas impacts. However, the most fundamental solution involves limiting natural gas expansion and instead accelerating renewable energy deployment. Given the urgency of climate action and the declining costs of clean energy alternatives, continued natural gas infrastructure investment represents economically irrational policy driven by incumbent industry interests rather than objective cost-benefit analysis.

The transition away from natural gas requires supporting affected workers and communities through retraining programs, economic diversification initiatives, and just transition policies ensuring energy workers access comparable employment in clean energy sectors. This social dimension remains essential for politically feasible transformation.

FAQ

What makes natural gas worse for ecosystems than coal?

Natural gas produces fewer direct combustion emissions than coal, but methane leakage throughout its supply chain creates significant climate impacts. Additionally, natural gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing causes habitat fragmentation, water contamination, and air quality degradation that coal mining operations in some regions avoid. The ecosystem impacts differ in character rather than representing unambiguous improvement over coal.

Can natural gas serve as a bridge fuel toward renewable energy?

The bridge fuel narrative assumes temporary natural gas infrastructure becomes abandoned as renewables scale. However, infrastructure lock-in effects mean natural gas plants continue operating 40-60 years after construction, potentially constraining renewable deployment. Moreover, the urgency of climate action means rapid renewable expansion rather than gradual transition represents the economically optimal pathway. Natural gas infrastructure built today likely persists beyond the 2050 timeframe when near-zero emissions become essential.

How significant is methane leakage compared to other greenhouse gases?

Despite methane representing only 10% of greenhouse gas emissions by volume, it contributes approximately 25% of warming forcing due to its high potency. Over 20-year timeframes critical for near-term climate outcomes, methane’s contribution to warming becomes even more significant. This high potency means that reducing methane emissions provides disproportionate near-term climate benefits.

What ecosystem services does natural gas development destroy?

Natural gas operations eliminate or degrade multiple ecosystem services including: carbon sequestration (through forest clearing), water filtration (through wetland destruction), flood regulation (through hydrological alteration), wildlife habitat provision, pollination services, and cultural/recreational values. Quantifying these services monetarily reveals that ecosystem service losses often exceed the economic value of natural gas extracted.

Are there successful examples of ecosystem restoration after natural gas operations?

While some degraded natural gas sites receive reclamation efforts, complete ecosystem restoration remains technically difficult and economically limited. Restored sites rarely recover the biodiversity and ecosystem function of pre-extraction conditions. This restoration limitation emphasizes the importance of prevention—protecting ecosystems from development rather than attempting post-extraction recovery.

How do natural gas impacts compare internationally?

Natural gas impacts vary geographically based on ecosystem sensitivity, regulatory stringency, and operational practices. Developing nations with weaker environmental enforcement often experience more severe impacts per unit of gas produced. Arctic and tropical ecosystems show greater vulnerability to natural gas impacts than temperate regions. However, no region escapes significant ecosystem consequences from natural gas development.