Conventional Farming’s Carbon Footprint: Study Insights

Conventional farming systems have become a significant contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for approximately 14-18% of worldwide carbon dioxide equivalent output. Recent comprehensive studies reveal that the agricultural sector’s environmental impact extends far beyond simple land use considerations, encompassing complex interactions between soil management, mechanization, chemical inputs, and livestock production. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for policymakers and agricultural stakeholders seeking to develop sustainable food production systems that balance economic viability with environmental stewardship.

The carbon footprint of conventional agriculture represents one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our era, yet it remains poorly understood by consumers and inadequately addressed in agricultural policy frameworks. As global population projections indicate we must feed nearly 10 billion people by 2050, the urgency of reforming farming practices becomes increasingly apparent. This comprehensive analysis examines the multifaceted ways conventional farming impacts environmental systems, synthesizing recent scientific research with economic data to provide actionable insights for stakeholders across the agricultural value chain.

Soil Degradation and Carbon Release

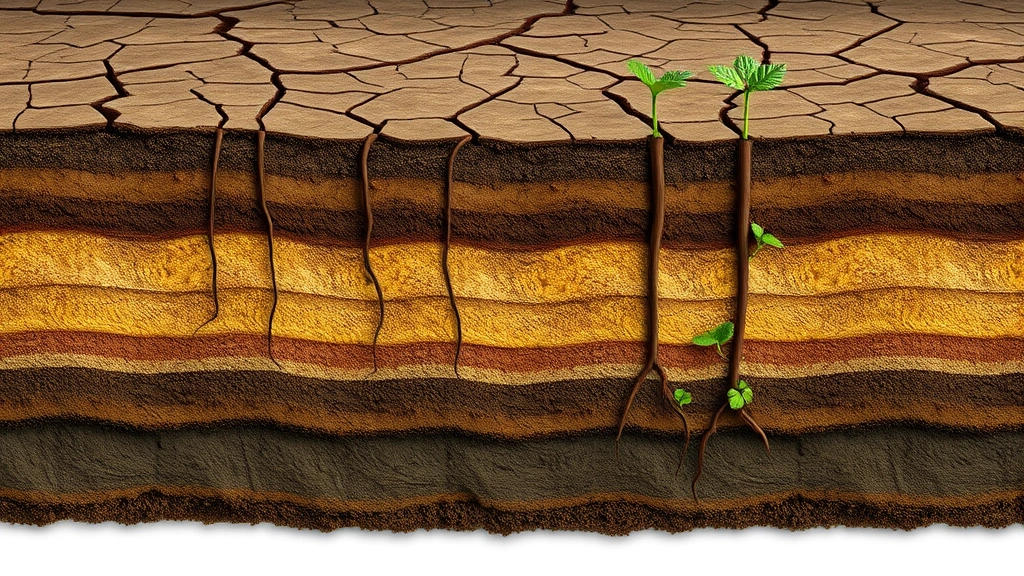

One of the most significant ways conventional farming impacts the environment is through soil degradation and the subsequent release of sequestered carbon. Conventional agricultural practices, particularly intensive tilling and monoculture cropping systems, fundamentally alter soil structure and organic matter composition. When farmers engage in repeated deep plowing and mechanical soil disturbance, they expose previously protected organic carbon to oxidation, converting soil carbon into atmospheric carbon dioxide at alarming rates.

Scientific research from the Food and Agriculture Organization indicates that conventional agriculture has depleted soil organic carbon stocks by approximately 50% compared to pre-industrial levels in many temperate regions. This carbon release represents not only current emissions but also the loss of the soil’s capacity to sequester future carbon. The relationship between soil health and climate regulation demonstrates a critical nexus between agricultural practices and atmospheric composition.

Monoculture systems, which dominate conventional farming landscapes, provide minimal organic matter inputs compared to diverse cropping or pastoral systems. Without adequate plant residue returning to soil, microbial communities decline, soil structure deteriorates, and carbon storage capacity diminishes. The degrading environment reflects these cumulative impacts across millions of hectares of cultivated land worldwide.

Furthermore, the absence of crop rotation in conventional systems means that nitrogen-fixing legumes rarely enter the rotation, requiring heavy reliance on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. This dependency creates a self-reinforcing cycle where soil biology becomes increasingly dependent on external chemical inputs rather than developing natural fertility mechanisms. The economic costs of this dependency extend beyond direct fertilizer expenses to include environmental externalities rarely captured in farm-level accounting systems.

Fossil Fuel Dependencies in Mechanized Agriculture

Conventional farming systems exhibit extraordinary dependence on fossil fuel energy inputs, creating substantial direct carbon emissions throughout the production cycle. Modern mechanized agriculture requires diesel fuel for tractors, harvesters, irrigation pumps, and transportation infrastructure. In industrialized nations, agricultural production consumes approximately 2-3% of total energy use, with the majority derived from fossil fuels. For individual farming operations, fuel costs often represent 10-20% of total production expenses, yet the associated carbon emissions extend well beyond these direct operational costs.

The energy intensity of conventional agriculture has increased dramatically over the past seventy years, as mechanization replaced human and animal labor. While this transition improved productivity metrics in the short term, it created structural dependency on petroleum-derived energy sources. A single hectare of conventionally managed corn or wheat may require 5-10 megajoules of fossil fuel energy input to produce annual yields, representing an energetic inefficiency compared to solar energy capture by crops themselves.

Transportation represents a secondary but significant source of fossil fuel consumption within conventional agricultural systems. The consolidation of food production into specialized regional systems, enabled by mechanization and subsidized transportation infrastructure, means that produce often travels thousands of kilometers from farm to consumer. This geographic separation creates “food miles” that substantially increase the carbon footprint of individual food items, even before considering storage, processing, and retail distribution.

Irrigation in water-scarce regions amplifies fossil fuel consumption, as pumping groundwater or surface water to agricultural fields requires continuous energy input. In regions like the American Great Plains or South Asian agricultural zones, irrigation-driven agriculture consumes enormous quantities of diesel fuel to maintain crop production during dry seasons. Climate change is intensifying this problem, as shifting precipitation patterns force farmers to irrigate more extensively, thereby increasing fossil fuel dependencies and associated emissions.

Synthetic Fertilizer Production and Emissions

The manufacture of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers represents one of the most carbon-intensive processes in the global food system. The Haber-Bosch process, which produces ammonia for fertilizer synthesis, consumes approximately 1-2% of global energy production and generates substantial greenhouse gas emissions. Natural gas serves as both a feedstock and energy source for ammonia production, meaning fertilizer manufacturing creates emissions at multiple stages of the production process.

Conventional farming’s reliance on synthetic fertilizers stems from soil degradation and monoculture systems that cannot sustain productivity through biological nitrogen fixation. This creates a fundamental economic and environmental problem: farmers must purchase expensive external inputs to maintain yields, while simultaneously degrading the biological capacity of their soils. The global synthetic fertilizer industry produces approximately 200 million tons annually, with nitrogen fertilizers accounting for roughly 50% of this volume.

Beyond manufacturing emissions, synthetic fertilizers create significant post-application environmental impacts. When excess nitrogen reaches waterways through runoff and leaching, it triggers eutrophication processes that create hypoxic dead zones in coastal ecosystems. The Gulf of Mexico dead zone, fed by Mississippi River agricultural runoff, encompasses approximately 6,000-7,000 square kilometers during peak summer conditions, representing a direct economic loss to fisheries and tourism sectors worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

The emissions intensity of nitrogen fertilizer production has declined modestly over recent decades due to process improvements, but global fertilizer application rates have increased far more rapidly than efficiency gains. This means total emissions from fertilizer production have continued rising despite technological advances. Understanding this dynamic is essential for how to reduce carbon footprint in agricultural systems, as fertilizer represents a discretionary input amenable to reduction through alternative management approaches.

Livestock Production’s Climate Impact

Livestock production within conventional agricultural systems generates substantial greenhouse gas emissions through multiple pathways. Cattle and other ruminants produce methane through enteric fermentation, a digestive process that releases methane directly into the atmosphere. Globally, livestock production accounts for approximately 14-18% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, with cattle ranching representing the largest single contributor within this sector.

Conventional livestock production systems, particularly concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), combine high stocking densities with monoculture feed production, creating compounded environmental impacts. The feed conversion inefficiency of livestock—requiring approximately 10 kilograms of feed to produce 1 kilogram of beef—means that the carbon footprint of animal agriculture encompasses not only direct methane emissions but also the entire carbon burden of feed crop production.

Manure management in conventional systems contributes additional emissions through anaerobic decomposition processes that generate both methane and nitrous oxide. The concentration of livestock in CAFOs creates waste management challenges that conventional approaches often address through lagoon systems or land application practices that maximize emissions rather than minimizing them. Alternative waste management approaches exist but remain underutilized due to economic incentives favoring conventional methods.

The expansion of livestock production to meet global protein demand has driven massive land use changes, particularly in tropical regions where cattle ranching has replaced forest ecosystems. This land use conversion represents a one-time carbon debt from forest clearance plus ongoing emissions from reduced carbon sequestration capacity. The Amazon rainforest, extensively cleared for cattle pasture and soy production for livestock feed, represents one of the most significant climate-related environmental injustices in contemporary agriculture.

Water Quality Deterioration

Conventional farming practices generate substantial water pollution through multiple mechanisms, creating cascading environmental and economic damages. Synthetic pesticides and herbicides leach into groundwater and surface water, contaminating drinking water supplies for millions of people globally. The polluter-pays principle, fundamental to environmental economics, remains inadequately applied in agricultural sectors where farmers bear minimal responsibility for water quality damages their practices create.

Nutrient runoff from conventional farms creates the previously mentioned dead zones while simultaneously degrading freshwater ecosystems through eutrophication. The economic value of ecosystem services lost through this degradation—including water purification, fish production, and recreation opportunities—vastly exceeds the financial gains from agricultural productivity increases that caused the damage. This represents a classic market failure where private agricultural profits are generated at the expense of public environmental and economic welfare.

Soil erosion, accelerated by conventional tilling practices and monoculture systems lacking diverse root structures, deposits massive quantities of sediment into waterways. This sedimentation reduces water storage capacity in reservoirs, degrades aquatic habitat, and increases water treatment costs for municipalities dependent on agricultural runoff. The World Bank estimates that soil erosion costs the global economy approximately $400 billion annually in lost agricultural productivity and environmental damages.

Pesticide contamination extends beyond direct toxicological effects to include endocrine disruption and bioaccumulation in aquatic food webs. Aquatic organisms exposed to agricultural pesticides exhibit feminization, immune system suppression, and reproductive dysfunction at concentrations far below direct lethal effects. These sublethal impacts cascade through ecosystems, reducing biodiversity and ecosystem resilience while creating long-term ecological debt that contemporary accounting systems fail to capture.

Biodiversity Loss and Ecosystem Services

Conventional agricultural systems, with their emphasis on monoculture production and chemical pest management, have decimated wild biodiversity across vast landscape areas. Approximately 68% of global biodiversity decline since 1970 correlates directly with agricultural land use intensification, habitat conversion, and pesticide application. This biodiversity loss represents not merely an aesthetic or ethical concern but a fundamental threat to ecosystem services that underpin food production itself.

Pollinator populations have declined precipitously in regions dominated by conventional agriculture, with honeybee colony losses exceeding 30% annually in some developed nations. Wild pollinator declines prove even more severe, with populations of bumblebees, butterflies, and other wild insects declining by 75% or more in intensively farmed regions over recent decades. These declines directly threaten crop pollination services worth an estimated $15-20 billion annually in developed agricultural economies.

Soil microbial communities, essential for nutrient cycling and disease suppression, have been devastated by conventional farming practices. The application of broad-spectrum fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides, combined with intensive tillage and monoculture cropping, has reduced soil biodiversity by 50-90% compared to natural or extensively managed ecosystems. This biodiversity loss impairs soil functioning and creates dependency on external chemical inputs to maintain productivity.

The loss of genetic diversity within agricultural systems represents another dimension of biodiversity decline. Conventional agriculture has replaced thousands of locally adapted crop varieties with a small number of high-yielding commercial cultivars. This genetic homogenization reduces adaptive capacity to climate change, pest pressure, and environmental variability, creating systemic vulnerability in global food security. The World Environment Day 2025 emphasizes restoration of ecosystem function, a process that cannot occur within conventional agricultural frameworks characterized by ongoing biodiversity destruction.

Economic Implications and Market Failures

The environmental damages generated by conventional farming represent classical economic externalities—costs imposed on society that are not reflected in market prices for agricultural commodities. When farmers apply synthetic fertilizers, they bear only the direct purchase cost while society bears the cost of water treatment, ecosystem restoration, and climate impacts. This pricing disconnect creates perverse incentives that encourage environmentally destructive practices while penalizing sustainable alternatives.

Ecological economics frameworks, developed by researchers at institutions like the United Nations Environment Programme, quantify these externalities at enormous magnitudes. Studies estimate that conventional agriculture generates environmental costs exceeding $1 trillion annually when accounting for soil degradation, water pollution, biodiversity loss, and climate impacts. These costs represent a hidden subsidy to agricultural producers and consumers that masks the true resource costs of food production.

Agricultural subsidies in developed nations further distort market signals, encouraging overproduction of commodities like corn and soybeans that depend heavily on conventional practices. The United States alone allocates approximately $20-40 billion annually in direct agricultural subsidies, with the vast majority supporting commodity crops produced through conventional methods. These subsidies incentivize practices that maximize short-term production while externalizing long-term environmental costs.

The economic inefficiency of conventional agriculture becomes apparent when full-cost accounting incorporates environmental externalities. Studies comparing conventional and organic systems find that when environmental costs are internalized, organic systems often demonstrate superior economic performance. However, current market structures reward conventional producers who externalize costs while penalizing sustainable producers who internalize environmental responsibility. Addressing these market failures requires policy intervention through mechanisms like carbon pricing, fertilizer taxes, or subsidy reallocation toward sustainable agriculture.

Transition Pathways to Sustainable Systems

Transitioning from conventional to sustainable agricultural systems requires multifaceted approaches addressing economic incentives, technological innovation, and institutional change. Regenerative agriculture, characterized by practices like cover cropping, reduced tillage, crop rotation, and integrated pest management, demonstrates capacity to reduce carbon footprint while maintaining or increasing productivity. Research from the World Bank indicates that transitioning to regenerative practices could sequester 0.5-1.5 gigatons of carbon annually while improving soil health and resilience.

Policy mechanisms to support transition include carbon pricing schemes that internalize climate costs, payments for ecosystem services that compensate farmers for environmental stewardship, and agricultural subsidy reform that redirects support toward sustainable producers. The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy reforms, which increasingly tie subsidy payments to environmental performance metrics, demonstrate feasibility of policy-driven transition at scale.

Technological innovations in precision agriculture, including variable rate application of inputs based on field-level conditions, can substantially reduce synthetic fertilizer and pesticide use while maintaining yields. Combining these precision technologies with biological approaches—such as microbial inoculants, biopesticides, and biological nitrogen fixation—creates hybrid systems that reduce chemical dependency without sacrificing productivity. Digital agriculture platforms enabling real-time monitoring and decision-making support optimization of these complex systems.

Institutional change requires engagement across multiple stakeholder groups including farmers, agricultural scientists, policymakers, and consumers. Educational programs supporting farmer transition to sustainable practices, research funding for agroecological innovation, and consumer demand for sustainably produced food all contribute to systemic transformation. Understanding the relationship between agricultural practices and broader sustainability goals, including urban design and environment considerations in food system resilience, supports holistic approaches to sustainable food production.

The economic transition to sustainable agriculture requires investment in soil building, biodiversity restoration, and ecosystem recovery—processes that generate returns over multi-year timeframes rather than single seasons. Financial mechanisms supporting this transition, including green bonds, impact investing, and blended finance structures, can mobilize capital for sustainable agricultural development. The Nature journal research on sustainable agriculture economics demonstrates that long-term financial returns from sustainable systems exceed conventional approaches when full costs are considered.

FAQ

What is the primary way conventional farming impacts the environment?

The most significant environmental impact is soil degradation and carbon release. Conventional practices like intensive tilling expose soil organic carbon to oxidation, converting sequestered carbon into atmospheric carbon dioxide. This simultaneously reduces soil’s future carbon storage capacity while generating immediate emissions, creating a double climate impact that fundamentally undermines long-term environmental sustainability.

How much of global emissions come from conventional agriculture?

Conventional agriculture contributes approximately 14-18% of global greenhouse gas emissions, making it a major contributor comparable to transportation sectors. When including land use changes driven by agricultural expansion, this figure can reach 20-25% of total anthropogenic emissions, making agricultural transformation essential for climate change mitigation.

Can conventional farming be made sustainable through technology alone?

Technology provides necessary but insufficient solutions. While precision agriculture and biotechnology can reduce input use and emissions intensity, fundamental transformation requires changing cropping systems, management practices, and economic incentives. Technology combined with agroecological practices and policy reform creates comprehensive approaches to sustainability that technology alone cannot achieve.

What are the economic costs of environmental damage from conventional farming?

Environmental externalities from conventional agriculture exceed $1 trillion annually according to ecological economics studies, including soil degradation costs, water pollution damages, biodiversity loss, and climate impacts. These costs vastly exceed the direct agricultural revenues generated, representing massive economic inefficiency masked by market failures.

How long does transition from conventional to sustainable agriculture take?

Transition typically requires 3-5 years as soil biology rebuilds and management systems adapt. However, productivity may decline during initial years before stabilizing at competitive levels. Financial support during transition periods and policy mechanisms ensuring market access for sustainably produced food accelerate adoption rates and reduce farmer financial risk.

What role do consumers play in reducing conventional agriculture’s impact?

Consumer demand for sustainably produced food creates market incentives for farmer transition while supporting premium pricing that compensates for transition costs. Additionally, dietary shifts toward plant-based proteins and reduced meat consumption decrease demand for resource-intensive livestock production, reducing pressure for agricultural expansion into remaining natural ecosystems.