Natural Gas Impact on Ecosystems: A Scientific Review

Natural gas has emerged as a transitional energy source in global climate mitigation strategies, yet its ecological footprint remains substantially underestimated in mainstream policy discussions. While promoted as a cleaner alternative to coal and oil, the extraction, processing, transportation, and combustion of natural gas generate cascading environmental consequences that affect atmospheric chemistry, hydrological systems, soil integrity, and biodiversity patterns across multiple scales. Understanding these impacts requires examining both direct physical disturbances and indirect biogeochemical alterations that reverberate through interconnected ecosystems.

The scientific consensus increasingly recognizes that natural gas cannot serve as a sustainable long-term energy solution without significant technological and regulatory interventions. Methane leakage throughout the supply chain, habitat fragmentation from infrastructure development, and the perpetuation of fossil fuel dependency create systemic ecological challenges that extend beyond carbon accounting frameworks. This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on natural gas’s environmental consequences, integrating findings from atmospheric science, ecology, hydrogeology, and ecological economics to provide policymakers and stakeholders with evidence-based insights for energy transition planning.

Methane Emissions and Atmospheric Impacts

Methane (CH₄) represents the primary greenhouse gas associated with natural gas operations, with atmospheric concentrations increasing by approximately 150% since pre-industrial periods. During extraction through hydraulic fracturing and conventional drilling, methane escapes from wellheads, processing facilities, and transmission infrastructure. The anthropogenic influence on atmospheric composition through methane emissions creates radiative forcing effects that accelerate warming trajectories independent of carbon dioxide pathways.

Research from the United Nations Environment Programme indicates that fugitive emissions from natural gas infrastructure account for 3-7% of total production volumes, substantially exceeding regulatory assumptions of 1-2%. These emissions occur across the entire supply chain: extraction sites experience direct venting; compression stations release pressurized gas; pipeline networks develop microscopic leaks; processing facilities emit during maintenance cycles; and distribution systems lose methane through aging infrastructure in urban environments. Over a 20-year atmospheric residence period, methane possesses a global warming potential approximately 80-86 times greater than carbon dioxide on a mass basis.

The tropospheric chemistry of methane generates secondary pollutants including ground-level ozone and hydroxyl radical depletion, which indirectly influence atmospheric self-cleaning capacity. Ozone formation in the boundary layer damages vegetation photosynthetic apparatus, reducing primary productivity in agricultural and natural ecosystems. This atmospheric degradation interconnects with broader environmental-societal relationships that determine ecosystem resilience and human adaptive capacity.

Habitat Disruption and Biodiversity Loss

Natural gas infrastructure development requires extensive landscape modification that fragments habitats, isolates wildlife populations, and disrupts ecological corridors essential for species migration and genetic exchange. Well pads, access roads, compressor stations, processing facilities, and pipeline rights-of-way collectively convert continuous ecosystems into fragmented patches with reduced interior habitat quality. Studies across North American shale gas regions document 40-60% declines in songbird populations in areas experiencing intensive development, with particular vulnerability in species requiring large territories or specialized breeding habitats.

The ecological consequences of habitat fragmentation extend beyond direct species loss to include edge effects that increase predation pressure, parasitism rates, and invasive species colonization. Noise pollution from compressor stations and drilling operations disrupts animal communication systems, affecting mate selection, territorial defense, and predator avoidance behaviors across multiple taxa. Light pollution from infrastructure creates circadian disruptions in nocturnal species and disorientation in migratory birds and insects, fundamentally altering behavioral patterns evolved over millions of years.

Wetland ecosystems experience particular vulnerability to natural gas development, as drilling activities and pipeline construction directly destroy these biodiversity hotspots while altering hydrological connectivity. Wetlands provide critical habitat for amphibians, waterfowl, and invertebrates while simultaneously functioning as carbon sinks and water filtration systems. The cumulative loss of wetland habitat through energy infrastructure development represents a cascading ecosystem service failure with ramifications for both human-environment interaction and intrinsic biodiversity value. Indigenous species adapted to specific microhabitat conditions face local extinction when development eliminates refugial areas, reducing genetic diversity and ecosystem functional redundancy.

Predator-prey dynamics shift in fragmented landscapes as apex predators require larger territories than available habitat patches can support, leading to mesopredator release and subsequent cascading effects through food webs. Plant communities in disturbed areas experience compositional shifts toward invasive species better adapted to edge conditions, further reducing native habitat quality and creating self-reinforcing degradation cycles.

Water Resource Contamination and Depletion

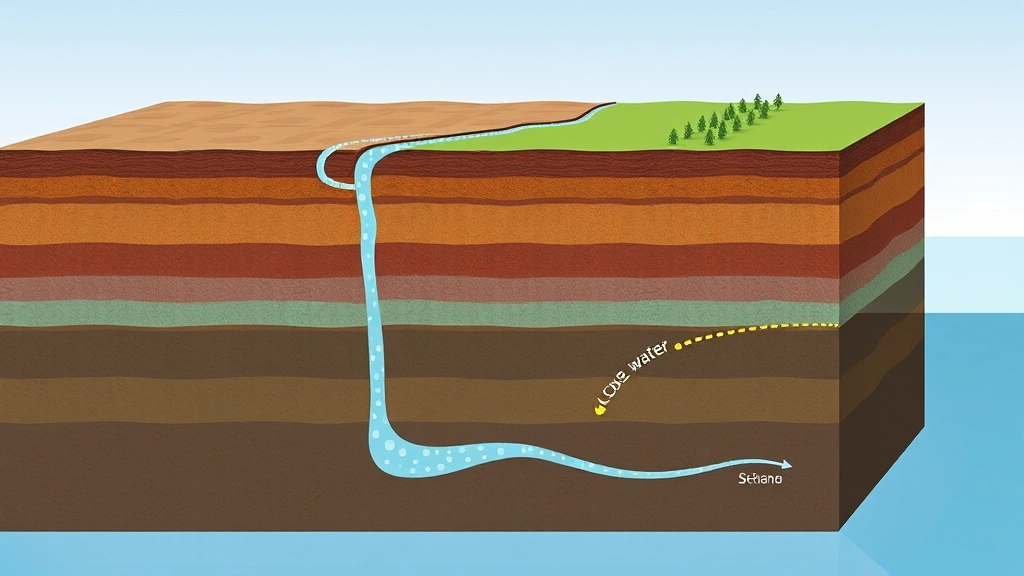

Hydraulic fracturing operations consume 2-20 million gallons of water per well, with significant regional variations based on geological conditions and shale formation properties. This water extraction directly competes with agricultural irrigation, municipal supplies, and ecosystem maintenance flows in water-stressed regions, particularly in the western United States where precipitation patterns show increasing variability. The World Bank’s water stress assessments identify natural gas extraction as an intensifying pressure on freshwater resources in already vulnerable watersheds.

Beyond volumetric depletion, the chemical composition of fracturing fluids—including surfactants, biocides, proppants, and undisclosed proprietary additives—creates contamination pathways into groundwater aquifers when well casings fail or fracture networks connect to potable water zones. Documented cases in Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, and Colorado demonstrate methane migration into drinking water supplies, with concentrations reaching explosive levels in some residential wells. The persistent nature of synthetic compounds used in fracturing fluids means contamination events create long-term water quality degradation extending decades beyond initial drilling activities.

Produced water—saline and chemically altered water extracted alongside natural gas—presents disposal challenges that often result in deep injection into non-potable formations, though mechanical failures and geological uncertainties create leakage risks. The radiogenic content of produced water (containing radium and uranium isotopes) creates additional contamination hazards in surface disposal scenarios. These water quality impacts intersect with broader patterns of environmental system degradation affecting both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystem functionality.

Aquifer depletion from intensive natural gas development reduces baseflow in streams and springs, fundamentally altering hydrological regimes that aquatic organisms have adapted to over evolutionary timescales. Reduced groundwater discharge decreases water availability during drought periods, intensifying stress on fish populations already experiencing thermal stress from climate warming. Riparian vegetation dependent on shallow groundwater experiences dieback in regions experiencing intensive groundwater extraction for both energy and agricultural purposes.

Soil Degradation and Land Use Changes

Infrastructure development for natural gas extraction creates compacted soils that reduce infiltration capacity, alter microbial community composition, and decrease carbon sequestration potential. Well pads, compressor stations, and access roads occupy relatively small absolute areas but create disproportionate impacts through soil disturbance that extends beyond direct footprints. Soil compaction reduces pore space, limiting root penetration and nutrient cycling processes essential for ecosystem productivity. The loss of soil carbon stocks through infrastructure development and associated vegetation removal contributes to atmospheric carbon accumulation independent of combustion emissions.

Land use conversion from native ecosystems to energy infrastructure represents a permanent or multi-decadal conversion of ecosystem services, with particular significance in ecologically sensitive regions including grasslands, forests, and wetlands. Native grassland soils developed over thousands of years contain complex mycorrhizal networks and microbial communities adapted to specific precipitation and temperature regimes; conversion to industrial land uses destroys these biological networks, with recovery timescales extending centuries even after infrastructure removal. Agricultural productivity in regions surrounding natural gas development declines due to soil disturbance, dust deposition, and hydrological alterations that reduce water availability during critical growth periods.

The accumulation of drilling waste—including drill cuttings, drilling muds, and other operational byproducts—creates soil contamination in disposal areas, with persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals creating long-term toxicity hazards. Remediation of contaminated soils requires expensive interventions and often remains incomplete, creating persistent environmental liabilities that transfer costs to future generations and reduce land value for productive uses.

Climate Forcing and Radiative Effects

The climate impact of natural gas extends beyond direct combustion emissions to include methane leakage, land use change carbon losses, and infrastructure-associated emissions across the entire lifecycle. Lifecycle analyses indicate that natural gas produces 40-50% lower combustion emissions than coal on a per-unit-energy basis, yet this advantage diminishes substantially when accounting for methane leakage, extraction energy requirements, and processing inefficiencies. Studies published in Nature Energy demonstrate that if methane leakage rates exceed 3.2% of production volumes, natural gas provides no climate benefit relative to coal for electricity generation over 100-year timeframes.

The radiative forcing contribution of natural gas-derived emissions includes both direct combustion CO₂ and methane leakage effects, with methane’s short atmospheric residence time creating near-term warming that dominates climate impacts during the critical 2030-2050 period when emission reductions must accelerate to limit warming to 1.5-2°C. This temporal dimension creates policy implications: investments in natural gas infrastructure lock in decades of emissions that conflict with rapid decarbonization requirements. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change increasingly emphasizes the incompatibility of expanded natural gas infrastructure with Paris Agreement climate targets.

Radiative forcing calculations must incorporate indirect effects including albedo changes from infrastructure development, atmospheric aerosol production from combustion, and cloud-nucleating properties of combustion byproducts. These indirect effects create additional warming beyond direct greenhouse gas accounting, though quantification remains subject to substantial uncertainty ranges. The cumulative radiative forcing trajectory of continued natural gas expansion demonstrates that this energy source cannot achieve climate stabilization goals without concurrent rapid deployment of renewable energy systems and dramatic emission reductions in other sectors.

Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services

Ecological economics frameworks increasingly recognize that market prices for natural gas fail to incorporate the full economic value of ecosystem services lost through extraction and infrastructure development. Valuation methodologies—including contingent valuation, hedonic pricing, and replacement cost approaches—consistently demonstrate that ecosystem service losses exceed $10-50 per million BTU when accounting for water depletion, soil carbon loss, habitat destruction, and air quality degradation. These externalized costs represent a massive subsidy to natural gas producers, effectively transferring ecological liabilities to society and future generations.

Wetland ecosystem services alone—including water purification, flood buffering, and wildlife habitat—are valued at $15,000-50,000 per acre annually in economic terms. Destruction of wetlands through pipeline construction and well development represents irreversible loss of these service flows, creating perpetual economic losses that accumulate across decades. Similar valuation approaches applied to forest carbon sequestration, groundwater recharge functions, and agricultural productivity impacts reveal that natural gas development generates negative economic returns when ecosystem service values are properly incorporated into cost-benefit analyses.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development has developed standardized frameworks for natural capital accounting that reveal natural gas development as economically irrational when full environmental costs are internalized. Regions implementing these frameworks—including portions of Scandinavia and New Zealand—have begun restricting natural gas expansion in favor of renewable energy systems that generate positive ecosystem service returns. The integration of ecological economics principles into energy policy represents a fundamental reorientation toward scientific understanding of environmental systems and their economic foundations.

Discount rate assumptions profoundly influence ecosystem service valuation, with lower discount rates reflecting intergenerational equity principles and revealing that natural gas development imposes net economic costs when accounting for long-term environmental degradation. Standard economic analyses employing 3-5% discount rates systematically undervalue future environmental losses, creating systematic bias toward present-day extraction. Ecological economics frameworks employing lower discount rates or sustainability constraints consistently demonstrate that natural gas development fails cost-benefit tests when ecosystem services are properly valued.

The employment and economic development arguments frequently advanced in support of natural gas expansion must be evaluated against ecosystem service losses and comparative employment opportunities in renewable energy sectors. Research from ecological economics institutes demonstrates that renewable energy development generates 2-3 times more employment per unit energy capacity than fossil fuel development, undermining labor-based justifications for continued natural gas expansion. Regional economic transition planning must incorporate these employment dynamics while accounting for ecosystem service preservation.

FAQ

What is the primary environmental concern associated with natural gas extraction?

Methane leakage throughout the supply chain represents the most significant environmental concern, as methane possesses 80-86 times greater warming potential than CO₂ over 20-year periods. Fugitive emissions from wells, pipelines, processing facilities, and distribution systems can reach 3-7% of production volumes, substantially exceeding regulatory assumptions. This leakage undermines natural gas’s climate benefits relative to coal and other fossil fuels.

How does natural gas development impact water resources?

Hydraulic fracturing consumes 2-20 million gallons of water per well, directly competing with agricultural and municipal supplies in water-stressed regions. Additionally, fracturing fluids and produced water create contamination pathways into groundwater aquifers, with documented cases of methane migration into drinking water supplies. Deep injection of produced water creates long-term disposal liabilities and potential leakage risks.

What biodiversity impacts result from natural gas infrastructure?

Infrastructure development fragments habitats, isolates wildlife populations, and disrupts ecological corridors. Studies document 40-60% declines in songbird populations in intensive development areas. Noise and light pollution disrupt animal communication and behavior, while wetland destruction eliminates critical habitat for amphibians, waterfowl, and invertebrates.

Can natural gas serve as a climate solution?

Natural gas can only provide climate benefits if methane leakage remains below 3.2% of production volumes over 100-year timeframes. Current leakage rates of 3-7% eliminate this advantage, making natural gas incompatible with Paris Agreement climate targets. Renewable energy systems provide superior climate outcomes without ecosystem service losses.

What is the economic value of ecosystem services lost through natural gas development?

Ecological economics frameworks value ecosystem service losses at $10-50 per million BTU, with wetland destruction alone representing $15,000-50,000 per acre in annual service losses. When properly incorporated into cost-benefit analyses, natural gas development generates net negative economic returns, revealing systematic undervaluation of environmental costs in current market pricing.

How does natural gas development affect soil quality?

Infrastructure development creates compacted soils that reduce infiltration capacity and alter microbial communities essential for nutrient cycling. Soil carbon stocks are lost through vegetation removal and disturbance, while drilling waste creates persistent contamination. Recovery of degraded soils requires centuries even after infrastructure removal.