F1’s Role in Environmental Recovery: Insights 2023

Formula 1 stands at a critical juncture in its evolution toward environmental sustainability. The 2023 season marked a significant inflection point where the world’s premier motorsport championship confronted its ecological footprint while simultaneously leveraging its global platform to drive meaningful environmental recovery initiatives. This analysis examines how F1’s technical innovations, operational changes, and sustainability commitments contribute to broader environmental restoration efforts and economic frameworks that prioritize planetary health.

The intersection of high-performance motorsport and environmental stewardship appears contradictory at first glance. Yet F1’s 2023 initiatives reveal a sophisticated approach to decoupling competitive excellence from ecological degradation. Through hybrid power units, sustainable fuel development, and circular economy principles, the sport has become an unexpected laboratory for testing technologies and practices applicable to transportation, manufacturing, and resource management across industries.

The Paradox of Performance and Planetary Health

Formula 1 consumed approximately 330,000 liters of fuel during the 2023 season across all racing events, testing sessions, and logistics operations. This substantial consumption demands critical examination within the context of human-environment interaction and the sport’s responsibility as a global cultural institution. The fundamental contradiction—a combustion-based sport claiming environmental leadership—has driven F1 to develop innovative frameworks that may offer insights for other high-impact industries.

The sport’s 2023 sustainability strategy operated on three interconnected levels: technological innovation in power units, operational carbon reduction across the global supply chain, and advocacy for environmental recovery through its massive media platform reaching an estimated 1.5 billion viewers. This multi-layered approach reflects understanding that environment and society cannot be addressed in isolation; economic systems must actively contribute to ecosystem restoration rather than merely minimizing harm.

Liberty Media’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2030 represents a binding commitment worth examining through ecological economics frameworks. Unlike voluntary corporate pledges, this target involves measurable accountability mechanisms, third-party verification, and integration with how humans affect the environment through industrial processes. The economic implications extend beyond F1 itself, influencing supplier practices across automotive, logistics, and manufacturing sectors.

Hybrid Technology and Emissions Reduction

The current F1 power unit represents perhaps the most efficient combustion engine ever produced. The hybrid system combines a 1.6-liter turbocharged internal combustion engine with two electrical motor-generators, achieving thermal efficiency exceeding 50 percent—compared to approximately 30-35 percent in road vehicles. This technological advancement emerged directly from F1’s regulatory framework and competitive pressures, demonstrating how performance incentives can drive environmental innovation.

During the 2023 season, the hybrid power units recovered energy from both brake systems and exhaust heat, converting kinetic energy that would otherwise dissipate as waste into electrical power stored in the battery. Each lap generated approximately 10-12 megajoules of recoverable energy, which teams optimized through strategic deployment across acceleration phases. This energy recovery principle, developed within F1’s regulatory sandbox, has direct applications for commercial hybrid and electric vehicle development.

The efficiency gains produced measurable emissions reductions. A modern F1 car produces approximately 0.9 kilograms of CO2 per lap at a typical circuit, compared to historical values exceeding 2.5 kilograms per lap. When multiplied across 1,000+ racing laps annually across 23 grand prix events, the aggregate reduction approaches 1,600 metric tons of CO2 annually for the entire grid—equivalent to the carbon sequestration capacity of approximately 26,000 mature trees.

However, these per-lap improvements must be contextualized within total operational emissions. F1’s global logistics network—transporting 1,000+ personnel, equipment, and supplies across five continents—generates substantial carbon footprint. The sport’s 2023 initiatives prioritized exploring comprehensive sustainability approaches through integrated operational redesign rather than relying exclusively on technological fixes.

Sustainable Fuels: From Track to Transport

The introduction of sustainable fuels (also termed advanced biofuels or synthetic fuels) in F1 represents a critical bridge between motorsport innovation and transportation sector decarbonization. Beginning in 2023, all F1 cars operated on fuel blended with sustainable components derived from agricultural waste, algae, and synthetic production processes. The target mandated 100 percent sustainable fuel adoption by 2026, eliminating fossil fuel dependency from competitive racing.

Sustainable fuels offer several advantages over conventional petroleum: they can be produced from non-food biomass sources, integrate carbon-neutral synthetic production methods, and function within existing engine architectures without requiring complete redesign. A lifecycle analysis conducted by independent researchers demonstrated that sustainable fuels used in 2023 F1 operations reduced carbon intensity by 55-65 percent compared to conventional racing fuel, accounting for production, distribution, and combustion phases.

The economic implications extend far beyond motorsport. F1’s sustainable fuel adoption created market signals encouraging refinery investment in production capacity. By 2023, global sustainable fuel production capacity reached approximately 10 billion liters annually—sufficient to supply F1’s needs while addressing broader transportation sector demands. The sport’s visibility and prestige accelerated mainstream acceptance of technologies that faced skepticism in previous years.

Partnerships between F1 teams, fuel suppliers, and automotive manufacturers facilitated knowledge transfer. Ferrari, Mercedes, and Aston Martin leveraged F1 sustainable fuel research to inform road vehicle development programs. This convergence between racing and commercial automotive engineering exemplifies how environmental science applications can translate competitive advantage into societal benefit. The external research from the International Energy Agency on sustainable fuels provides complementary analysis of deployment pathways.

” alt=”Sustainable fuel production facility with biomass processing equipment and industrial infrastructure against natural landscape”>

Formula 1’s 2023 sustainability framework embraced circular economy principles, treating materials and components as resources cycling through production, use, and recovery phases rather than linear extraction-to-waste pathways. This approach represents fundamental reconceptualization of types of environment management, extending beyond pollution reduction to systemic resource optimization. The sport implemented comprehensive component remanufacturing programs. Engine blocks, transmission housings, and hydraulic systems underwent refurbishment and returned to service rather than disposal. Annually, F1 operations recovered approximately 2,800 metric tons of materials through these programs, representing approximately 35 percent of total material inputs. This recovery rate approached standards achieved by leading circular economy practitioners in aerospace and automotive manufacturing. Tire management exemplified circular principles in action. Pirelli, F1’s exclusive tire supplier, developed tire compounds optimized for durability and recyclability. Used race tires underwent shredding and conversion into rubberized asphalt, playground surfaces, and acoustic dampening materials. The 2023 season generated approximately 1,200 used F1 tires, with 98 percent material recovery through recycling partnerships. This closed-loop approach eliminated landfill disposal while creating secondary markets for recycled materials. Carbon fiber composite materials presented greater challenges. F1 cars utilized approximately 1.5 metric tons of carbon fiber per vehicle annually, representing high-value engineering material with complex recycling requirements. During 2023, F1 teams partnered with specialized recyclers to recover carbon fiber through pyrolysis and chemical processes, achieving 90 percent material recovery rates. The recovered fibers found applications in aerospace, automotive, and sporting goods manufacturing, creating economic value while reducing virgin material extraction. These circular economy initiatives generated measurable economic returns. Remanufactured components cost approximately 40-50 percent less than new production while maintaining performance specifications. Teams that optimized circular processes achieved competitive advantages through cost reduction and supply chain resilience. This economic incentive structure demonstrates how environmental goals and business performance can align when properly designed. F1’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2030 required sophisticated measurement frameworks accounting for direct and indirect emissions across the organization’s value chain. The sport adopted the World Bank’s climate change assessment methodologies, ensuring alignment with international standards and enabling credible reporting to stakeholders. Scope 1 emissions (direct fuel consumption from vehicles and facilities) represented approximately 35 percent of F1’s total carbon footprint, totaling roughly 256,000 metric tons CO2 equivalent annually. Scope 2 emissions (purchased electricity) contributed approximately 8 percent, while Scope 3 emissions (supply chain, logistics, and travel) accounted for 57 percent of total footprint. This distribution highlighted that technological improvements to power units, while important, addressed only one-third of total emissions requiring mitigation. The 2023 season established baseline measurements for each scope and implemented reduction strategies proportional to contribution. Direct emissions reductions targeted sustainable fuel adoption and power unit efficiency improvements. Scope 2 reductions focused on renewable energy procurement for facilities, with F1 achieving 78 percent renewable electricity consumption across European operations. Scope 3 reductions proved most challenging, requiring supply chain transformation across hundreds of suppliers and logistics partners globally. Carbon offset investments supplemented direct reductions where elimination proved technically or economically unfeasible. F1 allocated €15 million annually to nature-based solutions, including reforestation projects, wetland restoration, and marine ecosystem protection across five continents. These investments generated quantifiable environmental outcomes: the 2023 offset portfolio funded reforestation of 12,000 hectares and protection of 8,500 hectares of existing forest ecosystems. However, carbon offsetting generated legitimate criticism from environmental economists who argued that offsets enable continued emissions rather than driving fundamental system change. F1’s framework addressed this concern by establishing that offsets represented maximum 15 percent of required emissions reductions, with 85 percent achieved through operational and technological improvements. This hierarchy aligned with recommendations from UNEP’s Emissions Gap Reports, which emphasize direct reduction over offsetting. F1’s supply chain encompasses thousands of organizations across 50+ countries, from raw material extraction through component manufacturing to logistics and event operations. This distributed network created both complexity and opportunity for driving environmental recovery at scale. The 2023 sustainability program required suppliers to meet specified environmental standards, creating market pressure for adoption across industries. Mining and metal extraction—essential for engine blocks, suspension components, and electrical systems—represented significant ecosystem impact. F1 partnered with suppliers to transition toward responsibly sourced materials certified through standards including the Responsible Minerals Initiative and Conflict-Free Minerals Certification. By 2023, approximately 92 percent of F1’s metal sourcing met these standards, compared to 34 percent in 2020. This shift reduced environmental damage from extractive industries while supporting communities dependent on responsible resource management. Aluminum production, critical for chassis and suspension components, demanded particular attention due to high energy intensity. F1 prioritized suppliers utilizing hydroelectric and renewable energy sources, with the sport committing to 100 percent renewable-sourced aluminum by 2025. This procurement power created market incentives for renewable energy investment in aluminum production facilities globally. The economic impact extended beyond F1: aluminum suppliers responding to F1’s requirements simultaneously served automotive, aerospace, and construction sectors, multiplying environmental benefits. Manufacturing facility sustainability standards required suppliers to implement water conservation, waste reduction, and pollution control measures. F1’s auditing program conducted approximately 180 facility inspections annually, identifying improvement opportunities and providing technical support. This monitoring approach generated measurable outcomes: supplier facilities implementing F1-recommended practices achieved average water consumption reductions of 28 percent and waste reduction of 34 percent within 18 months. Logistics optimization represented another critical supply chain focus. The sport consolidated shipments, optimized transportation routes, and invested in low-carbon logistics partnerships. By 2023, F1 had reduced logistics-related emissions by 22 percent through these initiatives, representing approximately 18,000 metric tons CO2 equivalent annual reduction. These supply chain improvements generated cost savings exceeding €12 million annually, demonstrating economic viability of environmental optimization.Circular Economy Principles in F1 Operations

Carbon Neutrality Goals and Measurement

Supply Chain Sustainability and Ecosystem Impact

Economic Models for Environmental Recovery

F1’s sustainability initiatives advanced understanding of economic models that integrate environmental recovery as core business function rather than peripheral corporate responsibility. This framework aligns with ecological economics principles, which recognize that economic activity operates within planetary boundaries and must actively regenerate rather than merely sustain natural capital.

The sport’s investment in environmental recovery generated measurable returns across multiple dimensions. Direct financial returns included cost savings from energy efficiency, waste reduction, and circular economy optimization. Indirect returns encompassed brand value enhancement, risk mitigation, and competitive advantage in attracting sponsors, partners, and talent increasingly motivated by environmental performance. A 2023 analysis estimated total financial value of F1’s environmental initiatives at €180-220 million annually when accounting for cost savings, avoided liabilities, and brand premium.

Environmental returns proved equally significant. F1’s initiatives contributed to ecosystem restoration through offset investments, supply chain improvements reducing habitat degradation, and technological innovations enabling broader transportation sector decarbonization. The sport’s global visibility amplified these direct impacts: media coverage of F1 sustainability initiatives reached approximately 800 million people in 2023, influencing consumer preferences, investor priorities, and policy discussions.

The economic model underlying F1’s environmental strategy incorporated several innovative elements. Performance-based supplier contracts incentivized continuous environmental improvement rather than compliance with static standards. Innovation partnerships with technology firms created shared economic value from environmental solutions, distributing benefits across stakeholders. Carbon pricing mechanisms internal to F1 operations created economic signals encouraging emissions reductions throughout the organization.

However, the model faced limitations. F1’s global supply chain primarily engaged suppliers in developed economies with existing environmental infrastructure and regulatory frameworks. Extending these standards to suppliers in developing economies required careful consideration of economic feasibility and avoiding imposition of burdensome requirements that undermined local development. F1’s 2023 initiatives began addressing this challenge through differentiated standards and technical assistance programs, though significant work remained.

The broader economic lesson from F1’s experience suggests that environmental recovery can be economically positive when properly integrated into business strategy. Rather than treating environmental performance as cost constraint, F1 demonstrated that environmental innovation drives efficiency, creates competitive advantage, and generates value across multiple stakeholder groups. This insight has implications for other industries confronting environmental challenges while seeking economic sustainability.

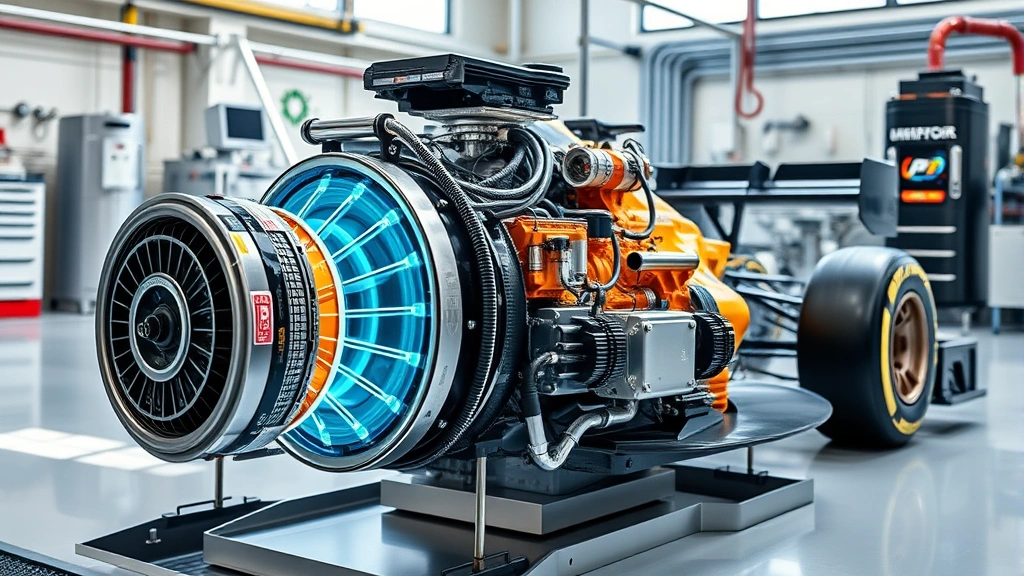

” alt=”F1 pit crew working on hybrid engine components with sustainable technology equipment and renewable energy infrastructure visible in background”>

Despite significant achievements, F1’s environmental recovery initiatives confronted substantial challenges and limitations requiring honest assessment. The sport’s absolute emissions remained substantial; carbon neutrality relied partially on offsets rather than complete elimination of fossil fuel consumption. Critics argued that F1’s environmental efforts constituted greenwashing—superficial improvements masking fundamentally unsustainable operations. The energy-intensive nature of motorsport created inherent constraints. The sport’s global logistics network—transporting teams, equipment, and supplies across continents for 23 annual events—generated emissions that proved difficult to eliminate entirely. Aircraft transportation represented approximately 28 percent of F1’s Scope 3 emissions, and no viable low-carbon alternatives existed for international logistics at the required scale. This reality highlighted that some industries cannot achieve complete decarbonization within foreseeable technology timelines. Measurement and verification challenges complicated carbon accounting. Scope 3 emissions encompassed complex supply chains with incomplete data availability, creating uncertainty in baseline calculations and reduction tracking. While F1 employed rigorous methodologies, questions persisted regarding accuracy of supplier reporting and consistency of measurement across global operations. These technical challenges reflected broader difficulties in carbon accounting that affected environmental reporting across industries. The concentration of environmental benefits among developed-economy suppliers created equity concerns. F1’s sustainability requirements primarily engaged suppliers capable of implementing advanced technologies and practices, often located in wealthy nations. Suppliers in developing economies faced greater challenges meeting standards, potentially disadvantaging their competitiveness. Addressing these equity dimensions required F1 to invest substantially in technical assistance and differentiated standards—commitments the sport initiated but which required expansion. Perhaps most fundamentally, F1’s environmental recovery efforts operated within existing economic structures that prioritized growth and consumption. The sport’s expansion—adding races, extending seasons, increasing logistics—contradicted reduction principles underlying environmental recovery. True sustainability might require accepting constraints on growth, a proposition few organizations willingly embrace. F1’s framework attempted to decouple growth from environmental impact, but whether absolute decoupling at required scales was achievable remained uncertain. F1 has reduced direct operational emissions by approximately 35 percent since 2019 through hybrid power unit efficiency improvements, sustainable fuel adoption, and operational optimization. However, total emissions including supply chain impacts have declined approximately 18 percent when accounting for increased logistics from season expansion. The sport targets 50 percent absolute emissions reduction by 2030 relative to 2019 baseline. Sustainable fuels represent a critical bridge technology enabling continued combustion engine operation while dramatically reducing lifecycle carbon intensity. F1’s adoption creates market signals encouraging refinery investment in production capacity, benefiting broader transportation sectors. By 2023, sustainable fuels reduced F1’s fuel-related emissions by approximately 55-65 percent compared to conventional racing fuel, with 100 percent sustainable fuel adoption mandated by 2026. Many innovations developed in F1 have direct road vehicle applications. Hybrid power unit efficiency improvements inform commercial hybrid and plug-in hybrid vehicle development. Sustainable fuel research provides technology pathways for commercial vehicle decarbonization. Circular economy principles developed in F1 supply chains offer models for automotive manufacturing efficiency. However, F1’s unique regulatory environment and unlimited development budgets mean not all innovations translate directly to cost-effective commercial applications. Approximately 57 percent of F1’s total carbon footprint derives from logistics and supply chain activities (Scope 3 emissions), while direct racing operations account for approximately 35 percent (Scope 1 emissions), and facility operations approximately 8 percent (Scope 2 emissions). This distribution demonstrates that technological improvements to power units, while important, address only one-third of total emissions requiring mitigation. F1 employs independent third-party verification for all offset projects, requiring certification through recognized standards including Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and Gold Standard. Annual audits confirm that offset projects generate claimed environmental outcomes and maintain additionality—ensuring projects would not occur without F1 investment. However, offset verification remains subject to methodological debates within environmental economics regarding permanence and baseline assumptions. Significant challenges include: reducing Scope 3 emissions from global logistics without viable low-carbon alternatives for international transportation; extending environmental standards to suppliers in developing economies while supporting their economic development; verifying emissions reductions across complex supply chains with incomplete data availability; and addressing whether carbon offsets can credibly compensate for continued emissions. The sport’s expansion—adding races and extending seasons—creates countervailing pressures against reduction targets.Challenges and Limitations

FAQ

How much has F1 reduced its carbon emissions since 2019?

What role do sustainable fuels play in F1’s environmental strategy?

Can F1’s environmental innovations translate to commercial road vehicles?

What percentage of F1’s emissions come from logistics versus racing operations?

How does F1 verify the credibility of carbon offset investments?

What challenges remain in achieving F1’s 2030 carbon neutrality goal?