Ecosystems and economies are fundamentally interconnected systems that shape human prosperity and environmental sustainability. For decades, economic models treated nature as an infinite resource, divorcing financial calculations from ecological realities. Today, cutting-edge research reveals that this separation was catastrophically incomplete. Ecosystems provide essential services—from pollination and water filtration to climate regulation and nutrient cycling—that underpin every economic transaction, yet most conventional GDP measurements fail to quantify their value.

The economic impact of ecosystem degradation extends far beyond environmental concerns. When coral reefs collapse, fishing communities lose livelihoods. When forests disappear, carbon storage capacity diminishes, accelerating climate change costs. When soil fertility declines, agricultural productivity plummets. Understanding these cascading relationships requires interdisciplinary analysis combining ecological science, economics, and systems thinking. This comprehensive examination synthesizes recent research to demonstrate how ecosystem health directly determines economic resilience, growth potential, and long-term prosperity.

Ecosystem Services and Economic Valuation

Ecosystem services represent the tangible and intangible benefits that natural systems provide to human societies and economies. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, conducted by over 1,300 scientists, categorized these services into four types: provisioning services (food, water, timber), regulating services (climate control, flood prevention, disease regulation), supporting services (nutrient cycling, soil formation), and cultural services (recreation, spiritual value, aesthetic appreciation).

Quantifying ecosystem value presents methodological challenges that economists have increasingly addressed through sophisticated valuation techniques. The World Bank estimates that natural capital—including forests, wetlands, fisheries, and mineral resources—comprises approximately 26% of total wealth in low-income countries, yet receives minimal investment or protection. Research published in Ecological Economics demonstrates that when ecosystem services are properly valued and incorporated into national accounting systems, they fundamentally alter cost-benefit analyses of development projects.

Consider pollination services: agricultural production worth over $15 billion annually depends on wild pollinator populations, yet these creatures receive no compensation in market transactions. Similarly, mangrove forests provide storm protection valued at thousands of dollars per hectare annually, yet are routinely cleared for aquaculture. The systematic undervaluation of ecosystem services represents what economists call a “market failure”—prices fail to reflect true scarcity and value. Understanding definition of environment science fundamentals helps contextualize why these valuation gaps persist.

Natural Capital as Economic Foundation

Natural capital encompasses all environmental assets—forests, fisheries, minerals, water, air quality, and biodiversity—that generate flows of goods and services supporting economic activity. Unlike manufactured capital, which depreciates predictably, natural capital exhibits complex threshold behaviors: ecosystems can suddenly collapse when stressed beyond critical tipping points, causing catastrophic economic losses.

The World Bank’s Wealth of Nations framework measures total wealth as the sum of natural capital, human capital, and produced capital. Analysis across 141 countries reveals alarming patterns: nations extracting natural capital faster than regeneration rates experience declining long-term prosperity despite short-term GDP growth. This dynamic mirrors unsustainable resource extraction—appearing profitable while depleting the underlying asset base. Countries dependent on single resources (oil, minerals, timber) demonstrate this vulnerability starkly: when resources deplete, economies collapse unless diversified alternatives developed.

Research from UNEP documents that ecosystem restoration investments generate economic returns exceeding 7:1 over decades, yet governments consistently underinvest in natural capital maintenance. The human environment interaction patterns reveal systematic underpricing of environmental degradation, enabling economically destructive activities to appear profitable through incomplete accounting.

Manufacturing capital depreciates at predictable rates; companies budget for replacement. Natural capital depreciation receives no such attention in most economic planning, despite evidence that ecosystem degradation accelerates unpredictably. A forest providing steady timber yields can suddenly collapse from pest outbreaks, disease, or climate stress. Fisheries can experience sudden recruitment failures. Aquifers can deplete irreversibly. These nonlinear dynamics demand precautionary approaches fundamentally different from conventional economic optimization.

Biodiversity Loss and Economic Consequences

Biodiversity—the variety of genes, species, and ecosystems—underpins ecosystem resilience and economic stability. The ongoing sixth mass extinction, driven primarily by habitat destruction and climate change, represents an unprecedented economic threat. Current extinction rates reach 100-1,000 times background rates, with cascading consequences for ecosystem function and economic productivity.

Research demonstrates clear correlations between biodiversity loss and reduced ecosystem service provision. Diverse ecosystems exhibit greater resistance to disturbance and faster recovery, providing more stable economic returns. Monoculture agricultural systems, while appearing efficient short-term, exhibit catastrophic vulnerability: the Irish Potato Famine, caused by genetic uniformity enabling potato blight, killed approximately one million people and triggered mass emigration. Modern agricultural biodiversity loss creates similar risks: three crop species provide 60% of global caloric intake, while thousands of traditional varieties disappear annually.

Pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries depend entirely on natural biodiversity. Approximately 25% of modern pharmaceutical drugs derive from rainforest plants, yet less than 1% of tropical plant species have been screened for medicinal properties. The economic value of potential undiscovered medicines vastly exceeds preservation costs, yet rainforests continue disappearing. The 10 human activities that affect the environment analysis reveals that habitat destruction—the primary extinction driver—generates immediate profits for extractive industries while imposing diffuse, long-term costs on society.

Pollinator decline exemplifies biodiversity loss economic consequences. Honeybee colony collapse disorder, linked to pesticide exposure and habitat loss, threatens crop production worth billions annually. Wild pollinator populations have declined 75% in some regions over recent decades. Insurance companies increasingly recognize pollinator loss as an emerging risk factor affecting agricultural insurance pricing and availability. Ecosystem service disruption translates directly into economic vulnerability.

Climate Regulation and Financial Risk

Climate regulation represents perhaps the most economically consequential ecosystem service. Forests, wetlands, and ocean ecosystems sequester atmospheric carbon, regulating global temperature. Forest loss accelerates climate change; deforestation accounts for approximately 10-15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This creates a perverse economic feedback loop: clearing forests for short-term agricultural profits accelerates climate change, which subsequently damages agricultural productivity through altered precipitation patterns, extreme weather, and pest range expansion.

The financial sector increasingly recognizes climate change as a systemic economic risk. Central banks, including the European Central Bank and Bank of England, classify climate change as a financial stability threat. Physical risks (extreme weather, sea-level rise, agricultural disruption) and transition risks (stranded assets in fossil fuel industries, policy shifts favoring renewables) threaten macroeconomic stability and financial system integrity. Ecosystem degradation accelerates both risk categories by reducing natural climate buffering capacity.

Research from ecological economics journals documents that climate damages could reduce global GDP by 5-20% by 2100 under high-emission scenarios, with developing nations experiencing disproportionate impacts. Paradoxically, the nations most vulnerable to climate change contributed least to atmospheric carbon accumulation. Small island nations face existential threats from sea-level rise despite negligible historical emissions. This distributional injustice creates geopolitical instability alongside economic disruption.

Natural climate solutions—ecosystem restoration, reforestation, wetland protection—provide cost-effective carbon sequestration while generating co-benefits: habitat restoration, improved water quality, enhanced agricultural productivity, and recreation opportunities. Yet these solutions receive minimal investment compared to technological approaches. The deforestation effects on the environment extend far beyond local impacts, influencing global climate patterns and economic stability across continents.

Water Systems and Economic Productivity

Freshwater ecosystems—rivers, wetlands, aquifers, and lakes—provide essential services supporting human economies: drinking water, irrigation, hydroelectric power, transportation, and industrial processing. Approximately 70% of global freshwater withdrawals support agriculture, making water availability a critical economic constraint in many regions. Yet ecosystem degradation increasingly threatens water security.

Wetland loss exemplifies this dynamic: wetlands filter pollutants, recharge aquifers, moderate flood intensity, and support fisheries. Despite comprising only 6% of land area, wetlands support 40% of species diversity. Since 1900, approximately 87% of global wetlands have disappeared, primarily converted to agriculture. This conversion generates immediate agricultural profits while eliminating water purification services previously provided free by natural systems. Municipalities must now construct expensive water treatment infrastructure to replace lost ecosystem function.

Water scarcity increasingly constrains economic activity. The World Bank estimates that water stress affects 4 billion people for at least one month annually, with this figure projected to increase as climate change alters precipitation patterns. Agricultural regions dependent on glacial melt face severe disruption as climate warming reduces snow accumulation and accelerates melt timing. The Himalayas, source of water for 2 billion people across South and Southeast Asia, face destabilization as glaciers retreat. This represents an unprecedented economic threat to regional food security and hydroelectric power generation.

Groundwater depletion presents equally severe challenges. The Ogallala Aquifer, underlying the American Great Plains and supporting 20% of U.S. irrigation, is being depleted faster than recharge rates by factors of 2-8. At current extraction rates, significant portions will become economically unproductive within decades. Similar situations exist in the Middle East, India, and China. Water scarcity increasingly drives geopolitical tensions; competition for shared water resources has historically triggered conflicts and will likely intensify as supplies tighten.

Agricultural Ecosystems and Food Security

Agricultural productivity depends fundamentally on ecosystem services: pollination, pest control, soil formation, water cycling, and nutrient provision. Industrial agriculture, while achieving high short-term yields through intensive input use, degrades the underlying ecosystem services upon which long-term productivity depends. Soil degradation, pesticide resistance in pest populations, pollinator decline, and water depletion create a trajectory toward declining productivity despite technological advancement.

Soil represents a critical but often overlooked natural capital asset. Fertile topsoil requires centuries to form yet can degrade to unproductive status within decades. Industrial agriculture loses approximately 24 billion tons of fertile soil annually through erosion. This degradation reduces productivity, increases fertilizer requirements, and causes downstream water pollution. The economic costs of soil degradation—reduced yields, increased input costs, pollution externalities—exceed $400 billion annually globally, yet receive minimal policy attention.

Pest management exemplifies how ecosystem degradation increases economic costs. Diverse agricultural landscapes support natural pest predators that suppress crop-damaging insects. Monoculture systems eliminate these predators, necessitating expensive chemical pesticide applications. Pesticide resistance evolves rapidly, requiring escalating chemical inputs and costs. Integrated Pest Management approaches, incorporating ecological principles through crop diversification and habitat preservation, reduce pesticide costs while improving long-term productivity. Yet adoption remains limited due to short-term economic incentives favoring monoculture.

Food security increasingly depends on ecosystem service preservation. The environment and natural resources trust fund renewal mechanisms demonstrate policy recognition of this relationship. Climate change, driven partially by agricultural expansion and associated deforestation, threatens productivity in major grain-producing regions. Wheat yields in key regions show declining trends despite technological improvements, driven by heat stress and altered precipitation. Economic models incorporating ecosystem service degradation project significant food price increases and supply instability.

Coastal Ecosystems and Blue Economy

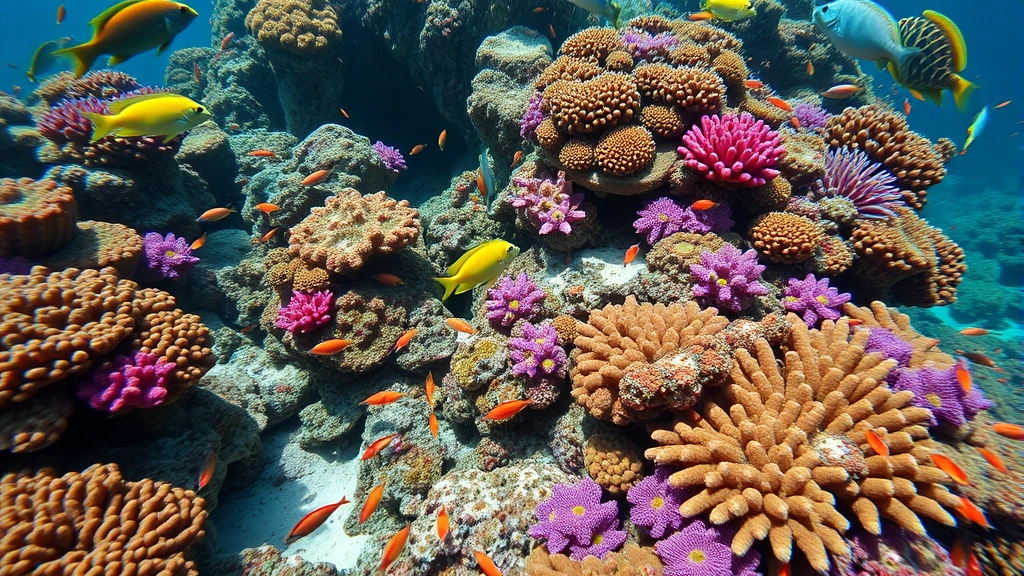

Coastal ecosystems—coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass beds, and estuaries—support the “blue economy” generating trillions in annual economic value through fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, and coastal protection. Approximately 3 billion people depend on marine and coastal biodiversity for livelihoods. Yet these ecosystems face unprecedented stress from overfishing, pollution, coastal development, and climate change.

Coral reef degradation illustrates ecosystem service collapse dynamics. Coral reefs support 25% of marine species despite covering less than 1% of ocean floor. They provide food security for 500 million people, generate $375 billion annually in economic value through fisheries and tourism, and protect coastlines from storm surge. Since 1950, approximately 50% of global coral reefs have degraded or disappeared. Continued warming threatens remaining reefs; projections indicate 90% of reefs will face severe bleaching by 2050 even under optimistic climate scenarios.

Mangrove forests provide equally critical ecosystem services: nurseries for commercially important fish species, water filtration, carbon sequestration, and storm protection. Yet 35% of global mangroves have disappeared since 1980, primarily cleared for aquaculture and coastal development. This conversion generates immediate profits for developers while eliminating natural storm protection, fishery support, and carbon sequestration services. When hurricanes subsequently cause coastal flooding, governments invest in expensive engineered defenses to replace lost natural protection.

Overfishing represents another critical threat to blue economy sustainability. Industrial fishing fleets, subsidized by governments, extract fish faster than reproduction rates. Approximately 35% of global fish stocks are overfished; another 58% are fully exploited. This trajectory leads inexorably toward fishery collapse, as demonstrated by the Atlantic cod fishery: once supporting hundreds of thousands of tons annually, it collapsed in the 1990s and remains depleted decades later despite fishing moratoria. Communities dependent on cod fishing experienced economic devastation. Similar collapses threaten other major fisheries.

Policy Integration and Economic Transformation

Addressing ecosystem-economy linkages requires fundamental policy transformation integrating ecological sustainability into economic decision-making. Current policy frameworks treat ecosystem degradation as an acceptable cost of economic growth, internalizing profits while externalizing environmental costs. Genuine economic sustainability demands reversing this dynamic: pricing ecosystem services appropriately, investing in natural capital maintenance, and restructuring incentive systems.

Natural capital accounting represents an essential policy innovation. Several nations—Costa Rica, Botswana, and others—have implemented comprehensive natural capital accounting systems measuring ecosystem service flows and degradation alongside conventional GDP. This accounting reveals that apparent economic growth often masks declining natural capital, indicating unsustainable trajectories. Integrating natural capital accounts into policy decisions shifts incentives toward sustainability.

Payment for ecosystem services mechanisms create direct economic incentives for conservation. Governments or private entities compensate landowners for maintaining forests, wetlands, or other ecosystems providing valuable services. Costa Rica’s payment for ecosystem services program has maintained forest cover and improved water quality while providing rural income. UNEP documents that well-designed PES programs generate positive economic returns while achieving conservation objectives.

Carbon pricing mechanisms internalize climate costs into economic calculations, making ecosystem conservation economically advantageous. Carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems increase fossil fuel costs while making forest preservation and ecosystem restoration economically competitive with extractive industries. However, current carbon prices remain too low to fundamentally shift incentives; economists recommend prices of $50-100+ per ton CO2 to drive necessary economic transformation.

Biodiversity offsetting policies attempt to compensate for habitat loss through restoration elsewhere. However, research increasingly questions offset effectiveness; restored ecosystems rarely replicate original ecological function. Precautionary approaches prioritizing habitat preservation over offsetting offer superior environmental and economic outcomes. The blog ecorise daily regularly examines policy innovations addressing ecosystem-economy integration.

International cooperation mechanisms recognize that ecosystem services transcend political boundaries. Migratory species conservation, ocean management, and climate regulation require coordinated international action. The Paris Climate Agreement, Convention on Biological Diversity, and other international frameworks attempt to align national policies with global ecosystem sustainability. Yet implementation remains inconsistent, with many nations prioritizing short-term economic gains over long-term sustainability commitments.

Economic transformation toward sustainability requires three fundamental shifts: First, price mechanisms must reflect ecosystem service values, internalizing previously externalized environmental costs. Second, investment priorities must shift from extractive industries toward ecosystem restoration and sustainable production. Third, policy frameworks must incorporate long-term ecological sustainability as binding constraints on economic activity rather than optional considerations.

FAQ

How much economic value do ecosystem services provide annually?

Global ecosystem services provide an estimated $125-145 trillion in annual economic value, approximately 1.5-2 times global GDP. This valuation includes provisioning services (food, water, materials), regulating services (climate, flood control, pollination), and cultural services. However, these estimates carry substantial uncertainty; many services resist precise valuation. The critical point is that ecosystem service value vastly exceeds conventional economic accounting, yet receives minimal investment protection.

Why do economists struggle to value ecosystem services?

Ecosystem services present valuation challenges because many lack market prices: clean air, pollination, climate regulation, and biodiversity have no established markets. Economists employ alternative valuation methods—contingent valuation (surveying willingness to pay), hedonic pricing (inferring value from property prices), replacement cost (estimating costs to replace services artificially), and others. Each method involves assumptions and limitations. Additionally, some ecosystem services resist monetization entirely: spiritual or cultural values, existence values for endangered species, and intrinsic value of nature defy market-based quantification.

Can technology substitute for ecosystem services?

Technology can partially substitute for some ecosystem services (water treatment plants replacing natural filtration, artificial pollination replacing natural pollinators) but at substantially higher costs and with reduced co-benefits. Technological substitution typically costs 2-10 times more than maintaining natural systems. Additionally, technology cannot substitute for all services: no artificial system can replicate complex climate regulation, soil formation, or genetic resource provision. Technological optimism that substitution enables unlimited ecosystem degradation represents a dangerous misunderstanding of ecological-economic relationships.

How do ecosystem impacts vary across economic development levels?

Low-income countries depend more heavily on natural capital (averaging 26% of total wealth versus 2% in high-income countries) yet face greatest ecosystem degradation pressures. Poverty drives unsustainable resource extraction; wealthy nations can afford conservation while poor nations prioritize immediate survival. This creates tragic dynamics where economically vulnerable populations experience greatest climate change impacts despite minimal responsibility for causing them. Equitable economic development requires supporting ecosystem conservation in developing nations through climate finance and technology transfer.

What economic indicators should replace or supplement GDP?

Genuine Progress Indicator, Gross National Happiness, and other alternative metrics incorporate ecosystem service values and income distribution alongside conventional production measures. These alternatives typically show declining economic progress in many wealthy nations despite rising GDP, reflecting ecosystem degradation and inequality. Transitioning policy focus toward comprehensive measures incorporating sustainability could fundamentally alter development trajectories. However, political resistance remains substantial; GDP retains dominance in policy discussions despite recognized limitations.