What Is the Physical Environment? A Quick Guide

The physical environment encompasses all non-living natural components that surround and support life on Earth. Unlike the biological environment—which includes organisms, ecosystems, and living systems—the physical environment comprises the abiotic elements: atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, and pedosphere. Understanding the physical environment definition is fundamental to environmental science, ecology, and sustainable development, as these components directly influence human welfare, economic productivity, and ecosystem health.

The distinction between physical and biological environments is critical yet often blurred in everyday discourse. While they function as interconnected systems, the physical environment provides the stage upon which biological processes unfold. Soil formation, water cycles, atmospheric composition, and geological processes are all physical phenomena that create conditions for life. Simultaneously, living organisms reshape their physical surroundings through weathering, nutrient cycling, and structural modifications. This guide explores the dimensions, characteristics, and economic implications of the physical environment, emphasizing why comprehending these fundamentals matters for informed environmental policy and sustainable resource management.

Core Components of the Physical Environment

The physical environment consists of four primary spheres that interact continuously: the atmosphere (gaseous layer), the hydrosphere (water systems), the lithosphere (solid Earth crust), and the pedosphere (soil layer). These spheres are not isolated; they exchange matter and energy through biogeochemical cycles, weather patterns, and geological processes. The atmosphere regulates temperature, distributes solar radiation, and facilitates precipitation. The hydrosphere stores, transports, and cycles water essential for all life. The lithosphere provides mineral resources, structural support, and geological stability. The pedosphere—the weathered upper layer of the lithosphere—supports terrestrial plant growth and microbial communities.

When examining the physical environment definition in scientific contexts, researchers emphasize its role as the abiotic foundation of all ecosystems. This contrasts with the broader concept of environment and environmental science, which integrates biological, social, and economic dimensions. The physical environment’s characteristics—such as temperature, pH, precipitation patterns, soil composition, and mineral availability—determine which organisms can survive in specific regions. Tropical rainforests thrive because of warm temperatures and high rainfall; deserts support drought-adapted species; alpine regions host cold-tolerant plants. These physical parameters create ecological niches and constrain biodiversity patterns across the planet.

Understanding these components requires interdisciplinary knowledge spanning geology, chemistry, physics, and meteorology. Physical geographers, environmental scientists, and ecological economists all examine how these spheres function and interact. The pedosphere, for example, represents a complex interface where mineral particles, organic matter, water, and air coexist. Soil development requires thousands of years, yet degradation can occur in decades—highlighting the temporal asymmetry between physical system formation and human-induced damage.

The Atmosphere and Climate Systems

The atmosphere comprises approximately 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, and 1% argon and trace gases including carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor. This gaseous envelope performs critical functions: regulating planetary temperature through the greenhouse effect, filtering ultraviolet radiation via the ozone layer, and distributing heat and moisture through wind patterns and precipitation systems. The atmosphere’s physical properties—density, pressure, temperature gradients—create weather phenomena and long-term climate patterns that influence agricultural productivity, water availability, and human settlement patterns.

Climate systems represent perhaps the most economically consequential aspect of the physical environment. The interaction between humans and the environment has intensified atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations from pre-industrial levels of 280 parts per million to over 420 ppm today. This concentration increase directly alters the atmosphere’s heat-trapping capacity, causing global temperature rise, precipitation pattern shifts, and extreme weather intensification. From an ecological economics perspective, climate change represents a massive externality—costs imposed on society that market prices fail to reflect.

Atmospheric circulation patterns—trade winds, jet streams, monsoons—distribute solar energy unevenly across latitudes and longitudes. These patterns determine regional climates, influencing where agriculture thrives, where water scarcity occurs, and where natural disasters concentrate. The physical atmosphere’s capacity to absorb and reflect solar radiation depends on aerosol concentrations, cloud cover, and greenhouse gas levels. Understanding these mechanisms requires physics-based models that predict how changes in atmospheric composition cascade through climate systems to affect human economies and natural ecosystems.

Water Systems and Hydrological Cycles

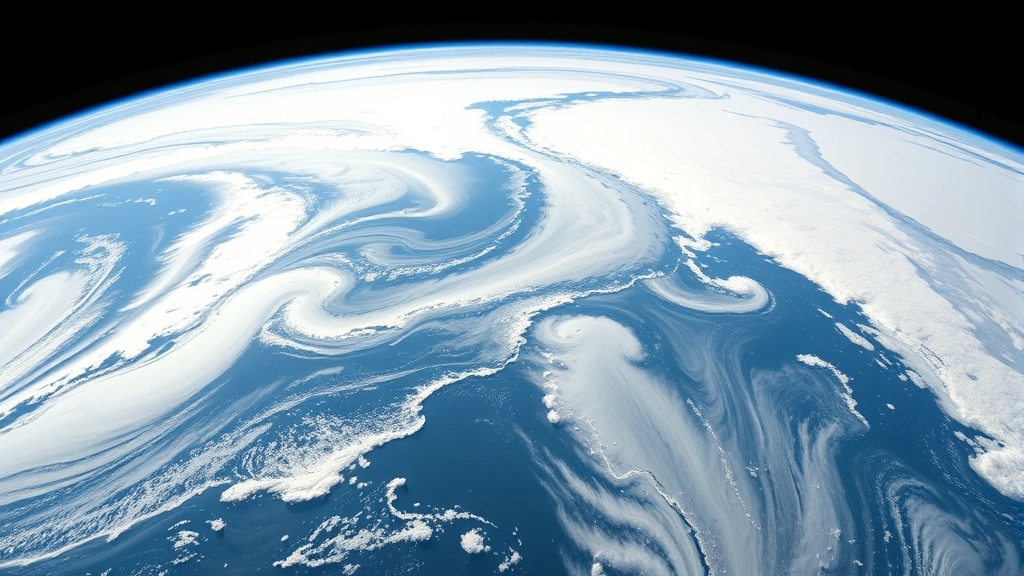

The hydrosphere—encompassing oceans, ice sheets, groundwater, lakes, rivers, and atmospheric water vapor—covers approximately 71% of Earth’s surface. Of this water, 97.5% is saline (ocean-based), leaving only 2.5% freshwater, with roughly 69% locked in ice caps and glaciers. This freshwater distribution has profound implications for human settlement, agriculture, and industrial activity. The hydrological cycle continuously circulates water through evaporation, transpiration, precipitation, infiltration, and runoff, driven by solar energy and gravitational forces. This physical cycle is fundamental to all life and ecosystem functioning.

Water quality and availability represent critical environmental and economic concerns. Water pollution affects the environment in cascading ways: contaminated freshwater reduces agricultural productivity, increases human disease burden, and degrades aquatic ecosystems. From a physical environment perspective, water pollution alters the chemical composition of hydrosphere components, reducing their capacity to support biological life. The World Bank estimates that water scarcity affects over 2 billion people globally, with projections suggesting that 5.7 billion people could face water scarcity for at least one month annually by 2050.

Groundwater represents approximately 96% of Earth’s liquid freshwater, stored in aquifers—porous geological formations capable of holding and transmitting water. These aquifers recharge slowly, at rates ranging from millimeters to meters per year depending on climate, geology, and land cover. Excessive groundwater extraction—particularly for irrigation—exceeds natural recharge rates in many regions, causing aquifer depletion. The Ogallala Aquifer underlying the American Great Plains, for instance, has declined significantly due to agricultural demand. This illustrates how the physical environment’s water storage capacity, while enormous in absolute terms, remains limited relative to human extraction rates in many regions.

Glaciers and ice sheets represent critical freshwater reservoirs and climate regulators. Mountain glaciers provide seasonal water flow to billions of people downstream; ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica store 68 meters of sea-level-equivalent water. Physical warming causes glacial retreat and ice sheet destabilization, with direct consequences for water availability and coastal flood risk. These processes involve fundamental physics: ice dynamics, heat transfer, and phase transitions between solid, liquid, and vapor states.

Land, Soil, and Geological Foundations

The lithosphere—Earth’s rigid outer shell comprising the crust and uppermost mantle—provides the geological foundation for all terrestrial life. Continental and oceanic crusts differ in composition: continental crust consists primarily of lighter silicate rocks (granite, basalt), while oceanic crust is denser and younger, continuously forming at mid-ocean ridges. Plate tectonics—the physical process by which lithospheric plates move, collide, and subduct—drives mountain building, volcanic activity, and earthquake generation. These geological processes operate over millions of years, yet their impacts on human societies can be catastrophic.

The pedosphere represents the weathered, biologically active upper portion of the lithosphere, where mineral particles, organic matter, water, and organisms interact. Soil formation requires the physical and chemical weathering of parent material—breaking down rocks into smaller particles through freeze-thaw cycles, chemical dissolution, and biological action. This process is extraordinarily slow: forming one centimeter of topsoil typically requires 100-400 years depending on climate and geology. Yet soil erosion from agricultural practices, deforestation, and urbanization can remove centimeters per decade, effectively mining accumulated soil capital.

Soil properties—texture, structure, pH, organic matter content, nutrient concentration—are determined by parent material, climate, topography, biological activity, and time. These physical and chemical properties determine water-holding capacity, nutrient availability, and plant root penetration. From an ecological economics standpoint, soil represents natural capital providing critical ecosystem services: water filtration, carbon storage, nutrient cycling, and biological habitat. Yet soil degradation—affecting approximately 33% of global land area according to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification—remains economically undervalued in market systems.

Mineral resources—metals, fossil fuels, industrial minerals—are concentrated in the lithosphere through geological processes operating over millions of years. Ore deposits form through hydrothermal circulation, magmatic differentiation, or sedimentary concentration. The physical distribution of these resources is highly uneven: some nations possess abundant mineral wealth while others have minimal deposits. This geological heterogeneity influences international trade patterns, geopolitical power dynamics, and economic development trajectories.

Physical Environment and Human Systems

The relationship between humans and the physical environment is fundamentally asymmetrical: humans depend absolutely on the physical environment’s functions and resources, yet humans possess unprecedented capacity to alter these systems. Human environment interaction has intensified dramatically since industrialization, with global material extraction increasing from approximately 4 billion tons annually in 1900 to over 100 billion tons today. This extraction encompasses fossil fuels, metals, non-metallic minerals, and biomass—all derived from the physical environment’s finite stocks and flows.

Human settlements concentrate in regions with favorable physical environments: coastal plains with adequate freshwater, moderate climates, navigable waterways, and fertile soils. Approximately 40% of humanity lives within 100 kilometers of coastlines, exploiting marine and terrestrial resources while facing flood and storm surge risks. Agricultural development requires specific soil types and climates; approximately 1.5 billion hectares globally are under cultivation, concentrated in temperate and subtropical regions with adequate precipitation. This spatial concentration creates resource competition and environmental pressure in productive regions while leaving marginal lands relatively undisturbed.

Economic development historically followed physical resource availability: coal-powered industrialization in regions with coalfields, hydroelectric development where topography and precipitation enabled dam construction, oil extraction in geologically favorable basins. Contemporary economic systems remain fundamentally dependent on the physical environment’s material flows, despite ideological assertions of economic dematerialization. Energy systems, food production, manufacturing, construction, and transportation all depend on extracting, processing, and transporting physical materials.

Economic Value of Physical Resources

From an ecological economics perspective, the physical environment represents the fundamental source of all economic value. Natural capital—stocks of environmental assets including minerals, fossil fuels, forests, fisheries, and freshwater—provides both extractive resources and ecosystem services. Yet conventional national accounting systems fail to depreciate natural capital as economies extract it, creating the illusion of sustainable growth when nations are actually liquidating accumulated natural wealth.

The World Bank’s extensive research on natural capital accounting demonstrates that properly accounting for environmental asset depletion dramatically alters perceptions of economic development. Nations with high resource extraction rates appear economically successful in conventional GDP terms, yet their genuine savings rates—accounting for natural capital depreciation—may be negative, indicating economic decline masked by resource depletion. This accounting framework reveals that unsustainable resource extraction redistributes wealth across time, benefiting current generations at future generations’ expense.

Ecosystem services provided by physical environment components—climate regulation, water purification, nutrient cycling, pollination, soil formation—have economic value even when markets fail to price them. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment estimated global ecosystem services at approximately $125 trillion annually, with many services declining due to environmental degradation. Reducing carbon footprint requires recognizing that atmospheric carbon absorption capacity—a critical ecosystem service—has been treated as free and infinite, leading to massive overexploitation.

Resource scarcity economics examines how physical resource constraints influence economic activity. Peak oil theory, for instance, addresses the physical reality that fossil fuel extraction follows logistic curves: initial rapid expansion, peak production, then decline as remaining reserves become more difficult and expensive to extract. While technological innovation can extend extraction possibilities, it cannot overcome fundamental thermodynamic constraints. The physical environment’s capacity to supply resources and absorb waste represents binding long-term constraints on economic expansion.

Monitoring and Managing Physical Systems

Scientific monitoring of physical environment components has expanded dramatically with satellite technology, sensor networks, and computational modeling. Global atmospheric CO₂ concentrations are measured continuously at Mauna Loa Observatory and other stations. Ocean temperature, salinity, and circulation patterns are tracked via satellite altimetry and buoy networks. Soil moisture, land cover change, and glacier extent are monitored from space. These monitoring systems provide quantitative data enabling scientists to track environmental change and validate predictive models.

Physical environment management involves multiple strategies: mitigation (reducing human impacts), adaptation (adjusting to unavoidable changes), and restoration (actively repairing damaged systems). Climate change mitigation requires reducing atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions through energy transition, industrial transformation, and lifestyle changes. Water management involves balancing extraction with recharge rates, protecting groundwater quality, and maintaining environmental flows for ecosystem health. Soil conservation requires reducing erosion through vegetation cover, terracing, and sustainable agricultural practices.

International environmental agreements increasingly recognize the physical environment’s limits and the need for binding constraints on resource extraction and pollution. The Paris Agreement commits nations to limiting atmospheric warming; the Convention on Biological Diversity addresses habitat loss; regional agreements regulate fisheries, water resources, and transboundary pollution. Yet implementation remains inconsistent, with economic incentives often favoring short-term extraction over long-term sustainability.

Ecological economics provides frameworks for integrating physical environment constraints into economic analysis. Unlike neoclassical economics, which treats the environment as a sector within the larger economy, ecological economics recognizes that the economy is embedded within and dependent on the physical environment. This perspective emphasizes biophysical limits, irreversibility, and uncertainty—recognizing that some environmental damage cannot be reversed and that human knowledge of complex systems remains incomplete.

FAQ

What is the physical environment?

The physical environment comprises all non-living natural components surrounding life on Earth: the atmosphere (gases), hydrosphere (water systems), lithosphere (solid Earth crust), and pedosphere (soil). These abiotic elements create conditions enabling biological life and provide resources supporting human economies.

How does the physical environment differ from the biological environment?

The physical environment includes non-living components (water, air, rock, soil), while the biological environment encompasses living organisms and ecosystems. They interact continuously—organisms alter physical systems while physical conditions determine which organisms can survive in specific locations.

Why is understanding the physical environment important?

The physical environment provides essential resources (water, minerals, soil, energy), regulates climate and weather, filters pollution, and determines human settlement possibilities. Understanding these systems enables informed environmental policy, sustainable resource management, and effective adaptation to environmental change.

How do humans impact the physical environment?

Humans extract resources (fossil fuels, metals, water, soil), generate pollution (greenhouse gases, chemical contaminants), alter land cover (deforestation, urbanization), and modify geological and hydrological systems (dams, aquifer depletion). These impacts accumulate globally, affecting climate, water availability, soil quality, and biodiversity.

What are the main threats to the physical environment?

Critical threats include climate change (atmospheric greenhouse gas accumulation), water scarcity (aquifer depletion, precipitation changes), soil degradation (erosion, contamination), deforestation (habitat loss, carbon release), and mineral resource depletion. These threats interconnect, with climate change exacerbating water and soil challenges.

How can individuals help protect the physical environment?

Individuals can reduce resource consumption, support renewable energy adoption, advocate for environmental policies, choose sustainable products like organic food benefits, support sustainable fashion brands, and participate in habitat restoration. Systemic change requires political and economic transformation, but individual choices collectively influence market demand and cultural values.