Are Ecosystems Intrusion-Proof? Expert Insights on Advanced Detection Systems

Ecosystems face unprecedented pressures from human activities, invasive species, pollution, and climate change. The question of whether natural systems possess inherent resilience against intrusion—or whether we need advanced detection mechanisms to monitor and protect them—has become central to conservation biology and ecological economics. Modern ecosystems operate as complex networks where even minor intrusions can cascade through food webs, disrupting services worth trillions of dollars globally. Understanding ecosystem vulnerability requires examining both natural defense mechanisms and technological solutions for early detection of threats.

The concept of ecosystem intrusion extends beyond simple invasion biology. It encompasses the broader framework of how external stressors penetrate ecological boundaries, alter biogeochemical cycles, and reduce ecosystem services. Advanced intrusion detection environments represent a paradigm shift in how we monitor, measure, and respond to environmental threats. By integrating real-time sensors, artificial intelligence, and ecological modeling, scientists can now identify disturbances at scales previously impossible to detect. This article explores whether ecosystems possess natural resistance to intrusion, what vulnerabilities exist, and how advanced detection systems are becoming essential tools for ecosystem protection.

Natural Ecosystem Defenses and Resilience Mechanisms

Ecosystems have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to resist intrusion and maintain stability. Biodiversity itself functions as a primary defense system—diverse communities possess functional redundancy where multiple species perform similar ecological roles. When one species declines due to intrusion, others compensate, maintaining critical ecosystem functions. Research from the World Bank’s environmental programs demonstrates that ecosystems with higher species richness recover faster from disturbances.

Physical and chemical barriers provide secondary defense layers. Soil microbial communities create networks that filter contaminants and prevent pathogenic intrusions. Forest canopies regulate light penetration and moisture, creating conditions hostile to invasive species. Wetlands naturally sequester pollutants through bioaccumulation and denitrification processes. These mechanisms represent millions of years of evolutionary optimization—what ecological economists call natural capital with immense economic value.

However, modern intrusions overwhelm these defenses. The velocity of climate change exceeds evolutionary adaptation rates. Invasive species arrive through global trade networks faster than native species can develop competitive responses. Pollution introduces synthetic compounds that evolved mechanisms never encountered. The human-environment interaction has fundamentally altered the scale and nature of intrusions ecosystems face, requiring us to develop artificial detection and response systems.

Types of Ecosystem Intrusions and Their Economic Impact

Ecosystem intrusions fall into several categories, each requiring different detection approaches. Biological intrusions include invasive species that outcompete natives and disrupt trophic relationships. The economic cost of invasive species globally exceeds $423 billion annually according to recent ecological economics assessments. Chemical intrusions encompass persistent organic pollutants, heavy metals, and microplastics that bioaccumulate through food chains. Physical intrusions include habitat fragmentation, dam construction, and coastal development that alter hydrological cycles.

Atmospheric intrusions—greenhouse gases, ozone-depleting substances, and particulate matter—represent perhaps the most pervasive threat. These intrusions operate at planetary scales, making detection and attribution challenging. Climate intrusions manifest as altered temperature regimes, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events that exceed ecosystem tolerance thresholds. Understanding these categories informs how we design detection systems and implement carbon footprint reduction strategies.

The economic valuation of intrusion impacts reveals staggering costs. Pollinator decline reduces agricultural productivity by $15-20 billion annually in the United States alone. Coral reef degradation threatens livelihoods of 500 million people dependent on marine ecosystem services. Forest ecosystem intrusions from pests and disease cost the global timber industry billions. These figures underscore why advanced detection systems represent sound economic investments—prevention costs far less than remediation.

Advanced Detection Technologies in Environmental Monitoring

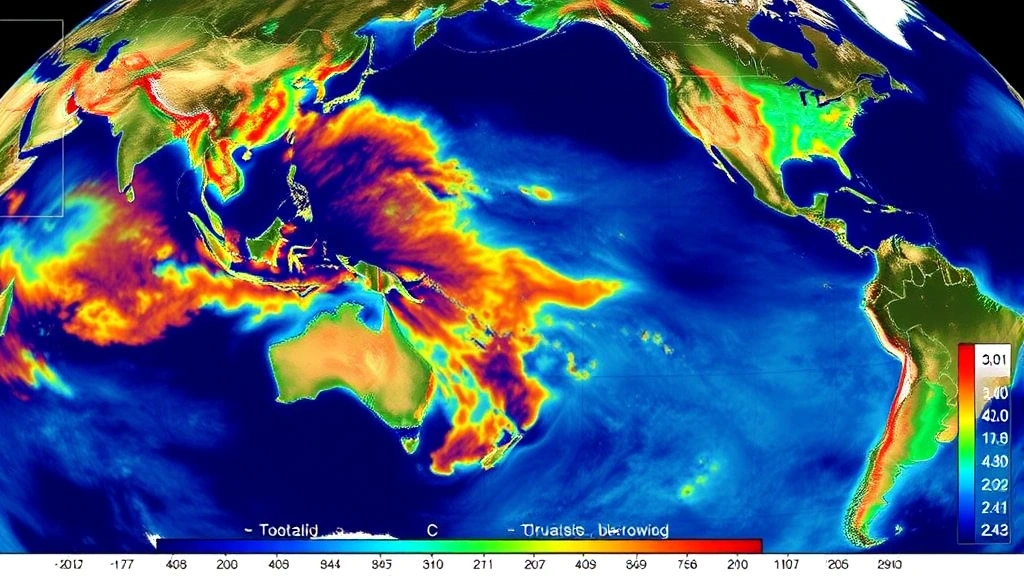

Modern advanced intrusion detection environments integrate multiple technological approaches. Remote sensing via satellites and drones provides landscape-scale monitoring with temporal resolution previously impossible. Multispectral and hyperspectral imaging detect vegetation stress, water quality changes, and land cover alterations. These systems generate petabytes of data daily, requiring machine learning algorithms to identify anomalies indicative of ecosystem intrusion.

Ground-based sensor networks create dense monitoring infrastructure. Wireless sensor nodes measure soil moisture, temperature, nutrient concentrations, and microbial activity in real-time. Environmental DNA (eDNA) monitoring detects species presence from water samples, revealing invasive organism arrival before population establishment. Acoustic monitoring identifies changes in soundscape ecology—shifts in insect, bird, and amphibian communities indicating ecosystem stress.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning enable pattern recognition across massive datasets. Neural networks trained on historical ecosystem data identify subtle changes signaling intrusion onset. Anomaly detection algorithms flag deviations from baseline conditions, triggering alerts for rapid response. Integration with natural environment research council frameworks ensures scientific rigor in detection protocols.

Bioinformatic approaches sequence microbial communities to detect pathogenic intrusions. Metagenomics reveals functional gene expression patterns indicating ecosystem stress. Metabolomic analysis identifies biochemical signatures of pollution or disease. These molecular-level detection systems operate at scales where traditional ecological monitoring proves inadequate, providing early warning of intrusions before ecosystem collapse.

Case Studies: Successful Intrusion Detection Systems

The Great Barrier Reef monitoring system exemplifies advanced detection integration. Underwater sensor networks measure temperature, pH, and coral bleaching indicators continuously. Satellite thermal imaging detects mass bleaching events in real-time, enabling rapid response protocols. Machine learning models predict bleaching events 6-12 months in advance based on water temperature anomalies. This system has improved intervention timing, protecting vulnerable coral populations from complete mortality.

Forest pest detection systems in North America employ integrated approaches combining aerial surveys, pheromone traps, and genetic analysis. Early detection of bark beetle infestations enables targeted management preventing landscape-scale devastation. The system’s economic value—preventing billions in timber losses—justifies substantial investment in monitoring infrastructure. UNEP’s environmental monitoring initiatives highlight similar successes in tropical forest protection.

Aquatic invasive species detection leverages eDNA technology in freshwater systems. Detection of zebra mussel larvae from water samples enables early intervention before population establishment. In the Great Lakes, this approach has prevented billions in infrastructure damage. The system demonstrates how molecular detection identifies intrusions at microscopic scales where traditional sampling fails.

Soil health monitoring networks integrate microbial genomics with chemical analysis. Detection of soil-borne pathogenic fungi enables preventive agricultural measures. These systems protect food security while reducing pesticide dependency. Economic analysis shows that early detection reduces crop losses by 15-30% compared to reactive management approaches.

Integration with Policy and Economic Frameworks

Effective ecosystem intrusion detection requires alignment with policy instruments and economic incentives. Payment for ecosystem services (PES) programs create financial motivation for monitoring and protection. Landowners receive compensation for maintaining ecosystem integrity, incentivizing adoption of detection technologies. Carbon credit systems similarly reward emissions reductions and forest conservation, with monitoring requirements driving advanced detection deployment.

Ecological economics frameworks value ecosystem services—pollination, water purification, climate regulation—in monetary terms. This valuation justifies investment in detection systems as cost-effective insurance against service loss. The World Bank’s green economy initiatives increasingly incorporate detection technology requirements into environmental lending conditions.

Regulatory frameworks mandate environmental impact assessment and monitoring. The European Union’s Water Framework Directive requires member states to monitor ecosystem health with specified detection methodologies. These mandates drive technological innovation and standardization. International agreements like the Convention on Biological Diversity establish monitoring targets, creating demand for advanced detection systems.

Corporate sustainability initiatives increasingly incorporate ecosystem monitoring. Supply chain transparency requires detection of illegal logging, water pollution, and habitat conversion. Companies invest in monitoring technology to verify sustainability claims and manage reputational risk. This market-driven adoption accelerates detection system deployment across industries.

Future Directions in Ecosystem Protection

Emerging technologies promise enhanced ecosystem intrusion detection. Quantum sensors offer unprecedented sensitivity for measuring environmental variables. Autonomous underwater and aerial vehicles enable persistent monitoring in remote ecosystems. Blockchain technology creates verifiable records of ecosystem status, supporting carbon markets and conservation financing.

Integration of traditional ecological knowledge with advanced monitoring creates hybrid approaches. Indigenous communities possess centuries of experience detecting ecosystem changes; combining this knowledge with technological systems enhances detection efficacy. This integration respects cultural sovereignty while improving environmental outcomes.

Climate adaptation strategies increasingly rely on detection systems to guide interventions. Assisted migration of species requires monitoring to ensure recipients ecosystems possess capacity for colonization. Ecosystem restoration efforts use detection systems to verify success and guide adaptive management. These applications demonstrate how detection technology becomes foundational to addressing climate change.

Economic models incorporating ecological thresholds and tipping points increasingly drive policy. Detection systems provide data enabling identification of critical thresholds before ecosystem collapse. This approach prevents costly emergency interventions, instead enabling proactive management. The shift from reactive to proactive ecosystem management represents fundamental change in how societies value and protect natural systems.

Ultimately, ecosystems are not intrusion-proof—they possess defenses that function effectively within historical environmental ranges but fail against novel, rapid, and intense modern stressors. Advanced detection systems represent humanity’s attempt to create artificial immune systems for nature. By identifying intrusions early, we preserve ecosystem resilience and maintain the services supporting human prosperity. The economic case is compelling: detection system costs pale against the value of ecosystem services protected. As technology advances and integration with policy deepens, ecosystem intrusion detection will become as fundamental to environmental management as building inspections are to structural safety.

FAQ

What is ecosystem intrusion detection?

Ecosystem intrusion detection refers to technological and methodological systems designed to identify threats to ecosystem integrity, including invasive species, pollution, habitat loss, and climate-driven changes. Advanced systems integrate remote sensing, sensor networks, artificial intelligence, and molecular analysis to provide early warning of ecological disturbances, enabling rapid response before catastrophic ecosystem collapse.

Can natural ecosystems defend against all intrusions?

Natural ecosystems possess remarkable resilience mechanisms including biodiversity, physical barriers, and biogeochemical cycles that filter contaminants. However, modern intrusions—characterized by unprecedented velocity, scale, and novelty—exceed evolutionary adaptation rates. Climate change, synthetic pollutants, and global trade-mediated invasive species overwhelm natural defenses, necessitating technological augmentation of detection and response capabilities.

How cost-effective are advanced ecosystem monitoring systems?

Advanced monitoring systems represent excellent economic investments. Prevention costs—early detection and intervention—typically cost 10-100 times less than remediation after ecosystem degradation. For invasive species, early detection can prevent billions in economic losses. For water quality monitoring, detection systems cost less than treating contaminated water supplies. Cost-benefit analyses consistently demonstrate positive returns on monitoring investments.

What role does artificial intelligence play in ecosystem monitoring?

Artificial intelligence enables pattern recognition across massive environmental datasets, identifying subtle anomalies indicating intrusion onset. Machine learning models predict ecosystem changes 6-12 months in advance, enabling preventive intervention. AI-powered image analysis processes satellite and drone data faster than human analysts, while anomaly detection algorithms flag deviations requiring investigation. These capabilities transform ecosystem monitoring from periodic sampling to continuous, intelligent surveillance.

How do detection systems support conservation and sustainability?

Detection systems provide objective data supporting conservation priorities and sustainability claims. Remote sensing identifies deforestation, enabling enforcement of protected areas. eDNA monitoring reveals invasive species, guiding eradication efforts. Water quality monitoring verifies pollution reduction efforts. This data supports carbon markets, payment for ecosystem services programs, and corporate sustainability reporting, creating economic incentives for ecosystem protection aligned with detection-based evidence.

Are there ethical concerns with intensive ecosystem monitoring?

Intensive monitoring raises questions about surveillance scope, data sovereignty, and indigenous rights. Remote sensing and sensor networks may infringe on community territories without consent. Data ownership questions arise—who controls ecosystem information and how is it used? Integration with traditional ecological knowledge requires respecting indigenous expertise and decision-making authority. Ethical monitoring frameworks increasingly address these concerns through community engagement, benefit-sharing, and collaborative governance structures.