How Economy Influences Ecosystems: New Study Reveals Critical Interconnections

Economic systems and natural ecosystems exist in a complex, bidirectional relationship that shapes the future of both human prosperity and planetary health. Recent research demonstrates that economic activities—from industrial production to agricultural practices—exert profound influences on ecosystem integrity, biodiversity, and resource availability. Understanding these connections is essential for policymakers, businesses, and individuals seeking to build sustainable futures.

A groundbreaking study published by the World Bank’s environmental economics division reveals that economic growth models failing to account for ecological limits create cascading failures across natural systems. The research highlights how pricing mechanisms, market structures, and investment priorities directly determine which ecosystems thrive and which collapse under pressure.

Economic Systems and Ecosystem Degradation

The relationship between economic activity and ecosystem degradation operates through multiple mechanisms. Industrial agriculture, extractive industries, and urban development represent the most visible pathways through which economic systems reshape landscapes. However, the influence extends far deeper into supply chains, financial markets, and consumption patterns that remain invisible to most consumers.

Contemporary economic models, rooted in 20th-century assumptions of infinite resources, systematically undervalue ecosystem services. When a forest is cleared for timber, the immediate economic gain appears substantial. Yet the loss of carbon sequestration capacity, water filtration, soil retention, and habitat provision—services worth billions annually—rarely appears on balance sheets. This accounting invisibility creates systematic incentives for ecosystem destruction.

Research from the United Nations Environment Programme documents that ecosystem degradation now costs the global economy approximately $125 trillion annually when accounting for lost natural capital and services. This figure dwarfs the GDP of every nation on Earth, yet remains largely absent from mainstream economic discourse.

The new study reveals that economic pressure on ecosystems intensifies during periods of rapid growth. Developing economies, seeking to expand GDP, frequently prioritize short-term extraction over long-term sustainability. Simultaneously, wealthy economies outsource environmentally damaging production to lower-income countries, creating a geographic separation between economic beneficiaries and ecological victims.

Market Failures in Environmental Valuation

At the core of economic-ecological conflict lies a fundamental market failure: the inability of price signals to reflect true environmental costs. When crude oil costs $80 per barrel, that price reflects extraction, refining, and distribution expenses—but not the atmospheric carbon accumulation, ocean acidification, or ecosystem disruption caused by combustion.

This pricing failure occurs because environmental systems exist outside traditional property rights frameworks. No individual owns the atmosphere or global climate system, so no market mechanism naturally internalizes climate impacts into prices. Fish populations in international waters lack ownership structures, enabling the tragedy of the commons where individual economic actors benefit from overharvesting while society absorbs the cost.

Ecological economics, an emerging discipline bridging environmental science and economic theory, proposes fundamental restructuring of how economies account for natural capital. Rather than treating ecosystems as infinite sources of raw materials and infinite sinks for waste, ecological economists model economies as subsystems embedded within finite planetary boundaries.

The study emphasizes that correcting these market failures requires deliberate policy intervention. Carbon pricing mechanisms, payments for ecosystem services, and natural capital accounting represent emerging tools for aligning economic incentives with ecological reality. However, implementation remains inconsistent and often insufficient to drive meaningful behavioral change.

The Cost of Externalities

Externalities—costs or benefits not reflected in market prices—represent perhaps the most economically significant aspect of economic-ecosystem relationships. When a coal plant generates electricity, consumers pay for generation costs, but respiratory disease, acid rain, and climate damage represent externalized costs borne by society broadly.

Agricultural externalities prove particularly extensive. Industrial farming systems generate enormous negative externalities through soil degradation, water contamination, pesticide accumulation, and pollinator collapse. A 2023 analysis found that conventional agriculture’s true cost—including environmental damage—exceeds its market price by 40-60% in developed economies. Farmers profit while society absorbs the ecological bill.

Conversely, ecosystems provide positive externalities that markets fail to compensate. A wetland filters water, prevents flooding, and sequesters carbon—yet landowners receive no payment for these services. This inverted incentive structure explains why wetlands face relentless conversion to commercial uses despite their enormous ecological value.

The new research demonstrates that as economic activity intensifies, externality costs grow exponentially rather than linearly. The hundredth coal plant causes more damage than the first, as it operates within an already-compromised atmospheric system. This non-linear relationship means that economic growth in heavily industrialized regions now generates negative returns when environmental costs are included.

Biodiversity Loss and Economic Consequences

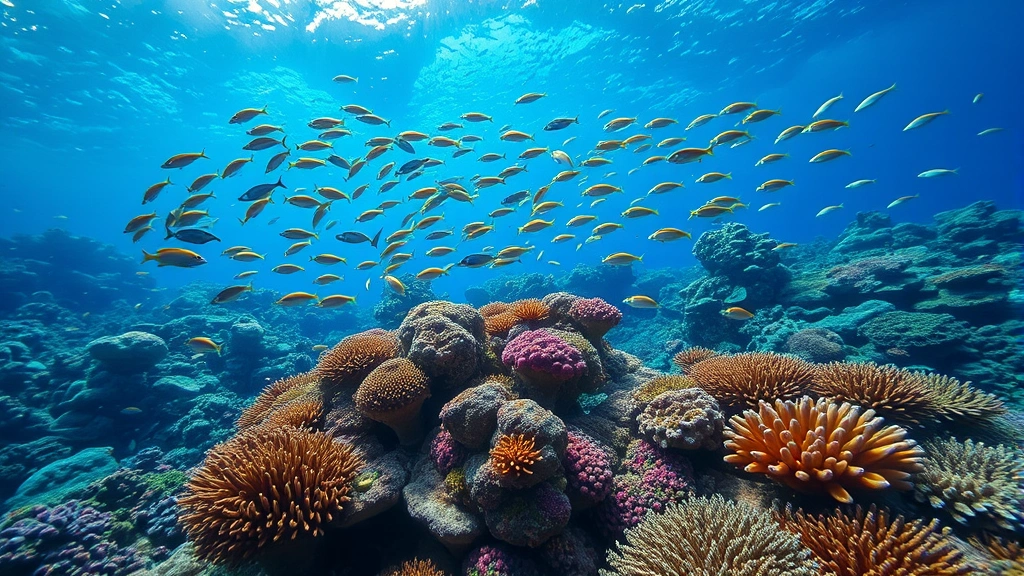

Biodiversity loss represents a direct consequence of economic expansion into remaining natural habitats. The study documents that 68% of global wildlife population decline correlates directly with economic growth rates in specific regions. Habitat conversion for agriculture, urbanization, and resource extraction drives approximately 80% of observed species extinctions.

The economic implications of biodiversity loss extend far beyond aesthetic or moral concerns. Ecosystem services dependent on biodiversity—pollination, pest control, disease regulation, genetic resources for pharmaceuticals—generate economic value exceeding $100 billion annually. As biodiversity declines, these services degrade, imposing costs on agricultural productivity, human health, and pharmaceutical innovation.

Insurance and reinsurance industries recognize these risks acutely. Climate change and ecosystem degradation create increasingly unpredictable natural disasters, rendering traditional risk models obsolete. Insurance costs for extreme weather protection now rise faster than actual premium income in many regions, signaling that economic systems face genuine existential risk from ecological collapse.

The pharmaceutical industry depends entirely on genetic diversity for drug discovery. Approximately 25% of modern pharmaceuticals derive from rainforest plants, yet less than 1% of tropical species have been tested for medicinal properties. As rainforests disappear for cattle ranching and agriculture, humanity loses potential treatments for cancer, diabetes, and neurological diseases. The economic value of this lost research potential exceeds the short-term gains from deforestation by orders of magnitude.

Transitioning to Regenerative Economics

Addressing economic-ecological conflict requires fundamental economic restructuring rather than marginal adjustments. Regenerative economics proposes that economic activity should actively restore ecosystem health rather than merely minimizing damage. This shift demands new measurement frameworks, investment criteria, and business models fundamentally different from extractive capitalism.

Natural capital accounting represents a crucial first step. By measuring ecosystem assets and their depreciation alongside financial assets, economies can track whether they genuinely grow or merely convert natural wealth into financial wealth. A nation that harvests its forests and fisheries while claiming GDP growth resembles a business liquidating assets while reporting profits.

The study highlights successful regenerative projects demonstrating economic viability. Regenerative agriculture, which rebuilds soil health through rotational grazing and diverse cropping, produces comparable yields to industrial agriculture while sequestering carbon and restoring water cycles. Restoration forestry generates long-term economic returns through ecosystem services while rebuilding biodiversity. Renewable energy systems now cost less than fossil fuels when accounting for health and environmental externalities.

Transitioning to regenerative economics requires reorienting investment flows. Currently, governments and institutions subsidize extractive industries to the tune of $7 trillion annually when accounting for unpriced environmental costs. Redirecting even a fraction of these subsidies toward regenerative activities would fundamentally alter economic incentives. Learning about how to reduce carbon footprint at individual and organizational levels represents one practical implementation pathway.

Policy Frameworks and Implementation

Translating economic-ecological insights into policy requires frameworks that align incentives with sustainability. Carbon pricing, whether through taxes or cap-and-trade systems, represents the most extensively implemented approach. Yet current carbon prices remain far below the true social cost of emissions—typically $5-50 per ton when climate damages alone cost $51-185 per ton.

Extended producer responsibility shifts environmental costs from society to manufacturers, incentivizing design for durability, repairability, and recycling. The European Union’s circular economy initiatives demonstrate that such policies can decouple economic growth from resource consumption, though implementation remains incomplete.

Biodiversity offsets attempt to compensate for habitat destruction through restoration elsewhere. However, the study identifies critical limitations: no restoration fully replaces lost ecosystems, offset quality varies enormously, and offsets can enable continued destruction if implemented without genuine additionality. Effective biodiversity protection requires preventing destruction rather than merely offsetting it.

Understanding human environment interaction at policy levels requires interdisciplinary teams combining economists, ecologists, and social scientists. Sustainable development goals provide frameworks, yet implementation often prioritizes economic growth over ecological thresholds. The research emphasizes that genuine sustainability requires accepting that some development activities cannot occur without exceeding planetary boundaries.

Financial regulation represents an underutilized policy lever. Requiring disclosure of climate and environmental risks in financial statements would force institutions to price these risks accurately. Stress-testing portfolios against ecological collapse scenarios would reveal systemic vulnerabilities currently invisible in financial models. Such reforms could redirect trillions in capital toward regenerative activities.

International cooperation proves essential given the global nature of ecosystems and supply chains. The study notes that unilateral environmental policies face competitive disadvantages when other nations maintain lax standards. However, trade agreements incorporating environmental standards and carbon border adjustment mechanisms could level competitive playing fields while incentivizing global ecological restoration.

Exploring renewable energy for homes and community-level solutions demonstrates that economic transformation can occur through distributed action. When individuals and communities transition to renewable energy, they simultaneously reduce emissions, create local economic activity, and build political support for systemic change.

FAQ

How do economists measure ecosystem damage in monetary terms?

Ecosystem damage valuation employs multiple approaches: replacement cost (what would it cost to replace ecosystem services artificially), hedonic pricing (how environmental quality affects property values), contingent valuation (what people state they would pay for environmental protection), and travel cost methods (how much people spend accessing natural areas). Each method has limitations, but triangulating across approaches provides reasonable estimates. The study emphasizes that perfect precision matters less than recognizing that current market prices systematically undervalue ecosystems by orders of magnitude.

Can economic growth and ecological restoration occur simultaneously?

Yes, but only if growth decouples from resource consumption and ecosystem destruction. Renewable energy sectors, restoration industries, and sustainable agriculture can generate economic activity while improving ecological health. However, this requires abandoning growth-at-all-costs mentality in favor of growth-within-limits frameworks. Wealthy nations must stabilize or reduce material consumption while developing economies transition directly to sustainable pathways, avoiding the resource-intensive development trajectory of industrialized nations.

What role do individual consumer choices play in economic-ecological relationships?

Individual choices matter, but systemic change requires far more than consumer responsibility. While reducing consumption and choosing sustainable products helps, the study emphasizes that 70% of global emissions derive from approximately 100 corporations. Systemic change requires policy intervention, corporate accountability, and investment redirection—not merely individual virtue. However, individual choices aggregate into market signals and political pressure that enable systemic change.

How do developing economies balance growth with environmental protection?

The research reveals that developing economies face genuine trade-offs between immediate poverty reduction and long-term sustainability. However, these trade-offs prove less severe than assumed. Renewable energy now costs less than fossil fuels in many contexts. Sustainable agriculture can match industrial yields while building soil health. The primary barrier involves financing: developing nations lack capital for infrastructure transitions without external support. International climate finance and technology transfer represent crucial mechanisms for enabling developing economies to pursue sustainable growth pathways.

What timeline exists for implementing economic-ecological reforms?

The study emphasizes urgency: critical tipping points in climate, biodiversity, and ocean systems approach within this decade. Implementing policy reforms requires 5-10 years for legislative passage and initial effects. Thus, delays of even 2-3 years substantially reduce feasibility of limiting warming to 1.5°C or preventing sixth mass extinction. The window for orderly transition remains open but rapidly closing. Delay increases transition costs and reduces available options, making immediate action economically rational even setting aside moral imperatives.