How Human Behavior Impacts Ecosystems: Study Insights

Human behavior fundamentally shapes the health and stability of Earth’s ecosystems. From consumption patterns to land-use decisions, our individual and collective actions cascade through natural systems, triggering measurable ecological consequences. Recent interdisciplinary research reveals that understanding the psychological, social, and economic dimensions of human behavior is essential to addressing environmental degradation and achieving sustainable development goals.

The relationship between human behavior and ecosystem integrity operates through multiple pathways. Consumer choices influence agricultural practices and deforestation rates. Industrial production decisions determine pollution levels and resource extraction speeds. Settlement patterns reshape habitats and fragment wildlife populations. This article synthesizes current research insights to explain how behavioral science, economics, and ecology converge in understanding—and ultimately reversing—our environmental impact.

Behavioral Foundations of Ecological Impact

Behavioral ecology and environmental psychology have established that human actions affecting ecosystems stem from both rational decision-making and cognitive biases. Traditional economic models assumed humans act as rational agents maximizing utility, but behavioral research demonstrates that emotions, social influences, and mental shortcuts substantially shape environmental choices.

The tragedy of the commons—where individuals pursuing self-interest deplete shared resources—remains a fundamental behavioral challenge. When ecosystem services lack clear property rights or pricing mechanisms, individuals lack immediate incentives to conserve. Overfishing in international waters, groundwater depletion in agricultural regions, and atmospheric carbon accumulation exemplify this dynamic. Research from the World Bank demonstrates that commons-based resource systems require institutional frameworks aligned with human behavioral tendencies.

Present bias—the tendency to prioritize immediate benefits over future consequences—profoundly influences environmental behavior. Extracting timber provides immediate income, while forest carbon sequestration and biodiversity benefits accrue over decades. This temporal mismatch between personal incentives and ecological outcomes creates systematic underinvestment in conservation. Studies show that when future impacts are psychologically salient or personally relevant, behavioral change becomes more likely.

Social identity and group behavior amplify individual environmental impacts. Consumption patterns reflect group membership and status signaling. The adoption of resource-intensive lifestyles correlates with peer influence and cultural aspirations more than with rational cost-benefit analysis. Conversely, environmental movements demonstrate that collective identity around sustainability can drive substantial behavioral shifts across populations.

Consumer Behavior and Resource Depletion

Global consumption patterns represent the primary driver of ecosystem degradation. The average resident of high-income countries consumes 5-10 times the resources of those in low-income regions, translating to vastly disproportionate ecological footprints. Understanding consumer behavior is essential because individual purchasing decisions aggregate into system-wide environmental consequences.

The rebound effect illustrates behavioral complexity in consumption. When energy efficiency improvements reduce the cost of driving, consumers often drive more miles, partially offsetting conservation gains. Similarly, reducing carbon footprint through one consumption category may be compensated by increased consumption elsewhere. Behavioral research indicates that framing matters enormously: presenting efficiency as cost savings versus environmental protection triggers different psychological responses and behavioral outcomes.

Fast fashion exemplifies how behavioral factors drive ecosystem destruction. The industry’s reliance on rapid trend cycles exploits psychological biases favoring novelty and social comparison. Consumers purchase garments worn only a few times before disposal, generating textile waste and driving unsustainable agricultural practices. Sustainable fashion brands succeed partly through reshaping social norms around clothing consumption, demonstrating that behavioral change can be commercially viable when aligned with consumer psychology.

Food consumption behaviors similarly cascade through ecosystems. Dietary choices influence land-use patterns, water consumption, pesticide application, and greenhouse gas emissions. Behavioral interventions—such as default options favoring plant-based proteins or transparent carbon labeling—shift consumption patterns without restricting choice, leveraging insights about how humans process information and make decisions.

Collective Action Problems in Ecosystem Management

Ecosystem degradation fundamentally involves collective action failures where individual rationality produces collectively irrational outcomes. When harvesting a shared fishery, each fisher gains full benefit from their catch while bearing only a fraction of the depletion cost. This creates a systematic incentive structure driving overexploitation regardless of individual environmental values.

The behavioral dynamics of climate change exemplify collective action challenges at planetary scale. Individual carbon emissions cause negligible personal climate harm while providing immediate convenience benefits. The diffusion of responsibility—where billions of people each make small contributions to a massive problem—psychologically obscures personal agency and accountability. Research shows that making climate impacts locally and personally relevant increases behavioral responsiveness more than abstract global statistics.

Institutional design profoundly shapes behavioral outcomes in commons management. Our blog explores how successful community-managed fisheries and forest systems incorporate monitoring, graduated sanctions, and conflict resolution mechanisms that align individual incentives with collective sustainability. These institutions work because they address behavioral realities: people respond to visible consequences, peer accountability, and fair rule-making processes.

International environmental agreements face behavioral obstacles in implementation. The Paris Agreement’s success depends on nations choosing climate action despite short-term economic costs. Behavioral insights suggest that transparency, peer comparison, and reputational concerns influence compliance more than formal enforcement mechanisms. Countries with strong domestic environmental movements and civil society oversight demonstrate higher commitment to climate pledges.

Psychological Barriers to Environmental Action

Multiple cognitive and emotional factors inhibit pro-environmental behavior despite widespread environmental concern. The attitude-behavior gap—where stated environmental values fail to translate into corresponding actions—reflects these psychological barriers. Research identifies several mechanisms:

- Psychological distance: Environmental impacts feel temporally remote (future generations), spatially distant (other regions), or probabilistically uncertain, reducing perceived personal relevance and motivational force

- Cognitive dissonance: Individuals maintain inconsistent beliefs about environmental harm and personal consumption, deploying rationalization and minimization to reduce psychological discomfort

- Moral licensing: Performing one environmental action reduces subsequent pro-environmental behavior, as individuals unconsciously balance moral self-image

- Information overload: Conflicting environmental messages and complexity overwhelm decision-making capacity, leading to inaction or status quo maintenance

- System justification: Psychological tendencies to rationalize existing social and economic systems reduce motivation to challenge environmentally harmful structures

The “finite pool of worry” suggests that environmental concerns compete with economic security, health, and social concerns for cognitive and emotional resources. During economic downturns or social crises, environmental priorities decline even when ecological degradation accelerates. This behavioral pattern explains why environmental movements gain traction during periods of economic stability and optimism.

Loss aversion—the tendency to weight losses more heavily than equivalent gains—creates asymmetric behavioral responses. Individuals resist environmental regulations perceived as losses (restricted consumption, increased costs) more strongly than they pursue equivalent gains (improved ecosystem services, health benefits). Framing environmental policies to emphasize gains rather than losses increases behavioral acceptance.

Economic Incentives and Behavioral Change

Economic instruments leverage behavioral responses to price signals and financial incentives. Carbon pricing, payment for ecosystem services, and subsidy reforms directly influence consumption and production decisions by changing relative costs and benefits. However, behavioral economics reveals that price signals interact with psychological factors in complex ways.

The environmental impact of fossil fuel use partly persists because carbon prices fail to fully internalize climate damages, leaving psychological barriers unaddressed. When carbon pricing is implemented alongside behavioral interventions—such as social norms messaging or commitment devices—effectiveness increases substantially. Research shows that combining price incentives with information about peer behavior produces 2-3 times greater energy conservation than price alone.

The United Nations Environment Programme documents how behavioral insights improve policy design. Automatic enrollment in renewable energy programs increases adoption rates from 10-20% to 60-80% without changing economic incentives, purely through leveraging behavioral defaults. Similarly, making environmental impacts visible on energy bills—rather than burying them in abstract numbers—triggers behavioral responses aligned with conservation.

Behavioral insights suggest that combining multiple policy instruments proves more effective than single mechanisms. Renewable energy adoption for homes accelerates when combining subsidies (economic incentive), information campaigns (reducing uncertainty), social proof (normative influence), and simplified decision-making processes (addressing cognitive barriers). This multi-faceted approach recognizes that human behavior responds to diverse motivational pathways.

Wealth effects complicate behavioral responses to economic incentives. Higher-income individuals show less price sensitivity for many goods, including energy and resource consumption. This suggests that achieving sustainable consumption patterns among affluent populations requires non-price interventions: social norm shifts, status signaling through sustainable choices, and institutional changes making sustainable options default.

Cultural Norms and Environmental Values

Cultural variation in environmental values and norms substantially influences ecosystem impacts. Indigenous communities practicing resource management across millennia demonstrate that cultural norms promoting intergenerational stewardship sustain ecosystems where short-term extraction would cause collapse. Behavioral research reveals that cultural narratives about human-nature relationships shape environmental decision-making as powerfully as individual rational calculation.

Social norm interventions prove remarkably effective at shifting environmental behavior. Informing households that their energy consumption exceeds neighborhood averages reduces usage by 1-3% annually—modest individually but substantial at scale. This works because humans are fundamentally social creatures responsive to peer behavior and group standards. Environmental quotes and narratives that reframe sustainability as social norm and status marker accelerate adoption more effectively than appeals to abstract environmental values.

Religious and spiritual traditions contain rich resources for environmentally-aligned behaviors. Stewardship concepts in Christianity, Islamic environmental ethics, Buddhist non-harm principles, and Indigenous reciprocity frameworks all provide cultural narratives supporting ecosystem conservation. Behavioral change accelerates when environmental action aligns with existing cultural and spiritual identities rather than conflicting with them.

Generational differences in environmental values create behavioral shifts in consumption and political preferences. Younger cohorts prioritizing climate action and sustainability show different behavioral patterns: lower car ownership, reduced meat consumption, and greater willingness to pay for sustainable products. As generational succession occurs, these behavioral shifts aggregate into systemic changes in production and consumption patterns.

Evidence-Based Mitigation Strategies

Effective environmental policy integrates behavioral insights with economic instruments and institutional design. Successful strategies address psychological barriers while realigning incentives:

- Simplification and defaults: Making sustainable choices the default option—renewable energy enrollment, sustainable procurement standards, plant-based meal defaults—leverages behavioral inertia and cognitive limitations toward environmental goals

- Social proof and norms: Highlighting peer behavior and community environmental action triggers conformity-based responses. Transparent environmental impact labeling and peer comparison mechanisms prove effective across consumer categories

- Commitment devices: Public pledges and binding commitments increase follow-through on environmental intentions by leveraging consistency motivation and reputation concerns

- Salience and framing: Making environmental impacts visible (carbon labels, ecosystem service valuation) and framing policies as gains rather than losses increases behavioral responsiveness

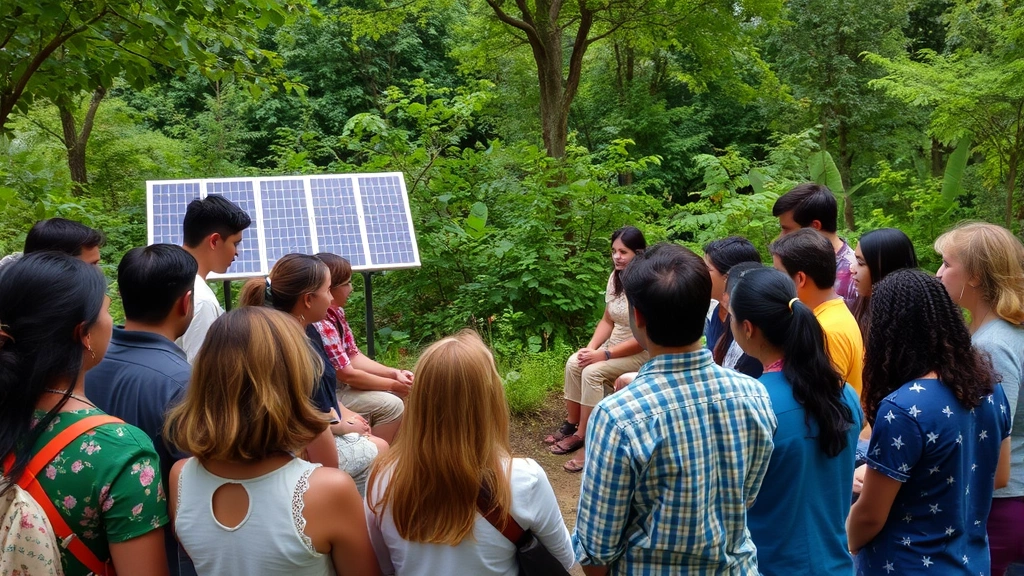

- Community engagement: Participatory decision-making in environmental governance increases behavioral compliance and environmental stewardship by addressing autonomy needs and distributional fairness

- Integrated policy design: Combining price signals, information provision, social influence, and structural change addresses multiple behavioral pathways simultaneously

Research from Ecological Economics journals demonstrates that behavior-informed policies achieve 20-50% greater environmental outcomes compared to traditional approaches. These insights prove particularly valuable where conventional regulation faces political resistance or where voluntary compliance determines policy success.

Institutional innovation addressing behavioral realities shows promise in ecosystem management. Community-based conservation programs incorporating local participation, transparent benefit-sharing, and peer accountability demonstrate higher sustainability than externally-imposed regulations. These institutions succeed because they align with human behavioral tendencies: people respond to fairness, reciprocity, and community membership more reliably than to abstract rules.

Scaling behavioral insights to global environmental challenges requires political will and institutional capacity. The OECD and major policy institutes increasingly incorporate behavioral economics into environmental policy design, recognizing that understanding human behavior is essential to achieving sustainability transitions. This represents a fundamental shift from assuming rational actors to designing systems that work with human behavioral tendencies.

FAQ

How do individual behaviors aggregate into ecosystem-scale impacts?

Individual consumption and production decisions compound across billions of people into system-wide environmental consequences. When millions adopt resource-intensive lifestyles, aggregate impacts exceed ecosystem regenerative capacity. Behavioral patterns—like consumption following peer behavior—create amplification mechanisms where small shifts in individual choices trigger large-scale environmental changes. Understanding these aggregation pathways explains why behavior-focused interventions can achieve substantial environmental gains.

Why do people care about the environment but fail to act accordingly?

The attitude-behavior gap reflects multiple psychological barriers: environmental impacts feel psychologically distant, competing priorities demand immediate attention, and individual actions seem inconsequential. Additionally, moral licensing allows people to feel they’ve done their part after minimal action, while cognitive dissonance reduction leads to rationalization of unsustainable choices. Behavioral interventions addressing these specific barriers—through commitment devices, social proof, and salience enhancement—prove more effective than information provision alone.

Can economic incentives alone drive sustainable behavior?

Economic incentives influence behavior but prove insufficient without addressing psychological and social factors. Price signals interact with behavioral biases, loss aversion, and social norms in complex ways. Combining economic instruments with behavioral interventions—social norms messaging, simplified decision-making, commitment devices—produces substantially greater environmental outcomes. This integrated approach recognizes that human behavior responds to diverse motivational pathways.

What role do cultural values play in environmental behavior?

Cultural narratives about human-nature relationships fundamentally shape environmental decision-making. Cultures emphasizing intergenerational stewardship, reciprocity with nature, or religious environmental ethics show greater commitment to ecosystem conservation. Environmental policies aligned with existing cultural values and social identities achieve higher behavioral compliance than policies conflicting with cultural frameworks. This suggests that sustainability transitions must engage cultural institutions and narratives.

How can institutions improve environmental outcomes through behavioral design?

Institutions addressing behavioral realities—through transparent decision-making, peer accountability, fair benefit-sharing, and participation opportunities—achieve higher environmental compliance and stewardship. Community-based conservation programs incorporating these elements demonstrate greater sustainability than externally-imposed regulations. Institutional design that aligns incentives with human behavioral tendencies proves more effective than relying on voluntary compliance or enforcement mechanisms alone.