AI’s Environmental Impact: What the Data Shows

Artificial intelligence has become one of the most transformative technologies of our era, powering everything from smartphone recommendations to complex scientific research. Yet behind every algorithm, neural network, and machine learning model lies a substantial environmental cost that often remains invisible to end users. The computational infrastructure required to train, deploy, and maintain AI systems consumes enormous quantities of electricity, water, and rare earth minerals, while generating significant carbon emissions that contribute to climate change and ecosystem degradation.

Understanding how AI is bad for the environment requires examining the data-driven reality of computational demands, energy consumption patterns, and the cascading ecological impacts across global supply chains. This analysis reveals that while AI offers tremendous potential for solving environmental challenges, the technology itself has become a notable contributor to the very problems it might help solve. The paradox demands urgent attention from technologists, policymakers, and environmental economists alike.

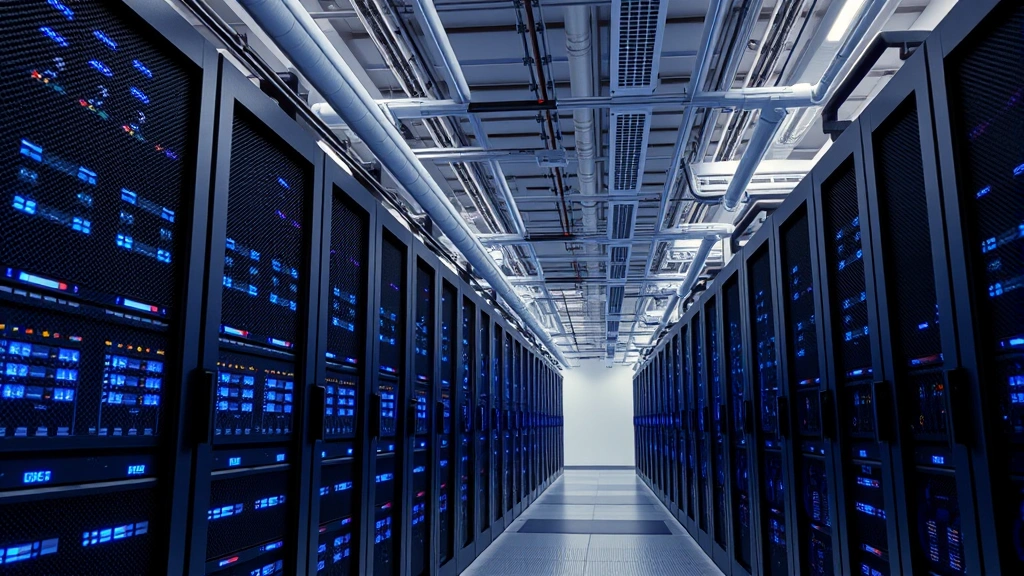

The environmental footprint of artificial intelligence extends far beyond simple electricity usage. It encompasses water consumption for data center cooling, mining operations for semiconductor production, electronic waste generation, and the geopolitical tensions surrounding resource extraction. This comprehensive examination of AI’s environmental impact provides the data-driven insights necessary to understand this critical issue and explore pathways toward more sustainable computational practices.

Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions

The electricity demands of artificial intelligence infrastructure represent one of the most quantifiable and concerning environmental impacts. According to research from World Bank analyses and independent studies, training a single large language model can consume between 50,000 to 700,000 megawatt-hours of electricity, depending on model complexity and optimization efficiency. To contextualize this figure: training OpenAI’s GPT-3 required approximately 1,287 megawatt-hours, equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of roughly 130 American households.

The carbon emissions trajectory becomes more alarming when examining cumulative impacts. The AI and information technology sector collectively accounts for approximately 2-3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, comparable to the aviation industry. This percentage continues accelerating as AI deployment expands exponentially across industries. Data centers alone consume 1-2% of global electricity, with AI-specific workloads representing the fastest-growing component of this demand.

Energy sourcing compounds these concerns significantly. While some major AI companies have committed to renewable energy targets, the reality remains that data centers often operate in regions where fossil fuels dominate the electricity grid. Facilities in areas dependent on coal or natural gas power essentially embed carbon emissions directly into every computational operation. The International Energy Agency projects that data center electricity demand will increase 50% by 2026, with AI being the primary driver of this growth.

Peak demand periods create additional inefficiencies. AI inference—the process of running trained models on new data—occurs continuously across billions of devices and servers worldwide. Unlike training, which concentrates computational load during specific periods, inference creates constant baseline demand that strains electrical grids and necessitates maintaining redundant capacity. This distributed consumption pattern makes carbon accounting and efficiency optimization substantially more complex than localized industrial processes.

Water Usage and Data Center Infrastructure

Water consumption represents an often-overlooked environmental dimension of AI infrastructure that carries profound implications for ecosystem health and human communities. Data centers require massive quantities of water for cooling systems that dissipate the heat generated by millions of processors operating simultaneously. Estimates suggest that AI-related data centers consume between 0.5 to 1 liter of water per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated, translating to billions of gallons annually across global facilities.

Particular concern emerges in water-stressed regions where data center development concentrates. Google’s data centers in Iowa, for instance, have faced scrutiny over water withdrawals from local aquifers during drought periods. Microsoft’s underwater data center experiments, while innovative, represent attempts to mitigate water scarcity conflicts rather than fundamental solutions. The competition between computational infrastructure and agricultural, municipal, and ecosystem water needs creates genuine resource allocation dilemmas with no easy resolution.

The quality of water returned to ecosystems matters equally to quantity consumed. Data center cooling often involves chemical treatments and thermal pollution, altering aquatic ecosystems’ chemical composition and temperature regimes. These modifications disrupt breeding cycles, oxygen levels, and microbial communities upon which entire food webs depend. Warming local waterways affects fish populations, amphibians, and the broader biodiversity that depends on specific thermal conditions.

Geographic concentration of data centers amplifies these impacts. Rather than distributing infrastructure globally, economic incentives and technical efficiency drive consolidation in specific regions with favorable conditions—cheap electricity, existing infrastructure, or temperate climates for cooling. This creates acute pressure on local water systems that may lack regulatory frameworks or political power to resist extraction demands from multinational technology corporations. Indigenous communities and developing nations frequently bear disproportionate environmental costs from infrastructure serving wealthy markets.

Mining and Resource Extraction

The minerals and rare earth elements embedded in AI hardware originate from mining operations that devastate ecosystems and displace communities. Producing semiconductors requires silicon, but also copper, aluminum, gold, tantalum, and cobalt—elements extracted through processes that destroy forests, contaminate groundwater, and generate toxic waste. A single data center containing millions of processors represents the cumulative extraction impact of thousands of mining sites worldwide.

Cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo exemplifies these dynamics’ human and ecological dimensions. Approximately 70% of global cobalt production originates from this region, where mining operations operate with minimal environmental regulation, creating acid mine drainage that acidifies waterways and kills aquatic life across vast areas. The same water sources that mining pollutes supply drinking water and irrigation for surrounding communities, creating public health crises alongside ecosystem collapse.

Rare earth element extraction, concentrated in China, Indonesia, and Myanmar, involves processing techniques that generate radioactive waste and acidic leachates contaminating soil and water systems. Processing one ton of rare earth minerals can produce up to 2,000 tons of toxic waste. These environmental liabilities remain externalized from market prices, meaning AI infrastructure costs appear artificially low because mining communities and ecosystems bear true expenses.

Supply chain complexity obscures accountability. Semiconductor manufacturers purchase materials from intermediaries who source from dozens of mining operations across multiple countries. This fragmented supply chain enables plausible deniability regarding environmental and labor standards. Technology companies can claim ignorance about mining practices while benefiting from cost reductions that mining externalities enable. Transparency initiatives and supply chain auditing remain nascent, leaving most AI infrastructure’s upstream environmental impacts unmeasured and unaccounted.

The geopolitical dimension adds urgency to these concerns. As AI competition intensifies between nations, pressure increases to secure mineral supplies regardless of environmental consequences. Strategic mineral reserves become national security priorities, potentially accelerating extraction timelines and reducing environmental oversight. This dynamic mirrors historical patterns where resource-rich regions experience accelerated exploitation during technological transitions, with local ecosystems bearing costs while distant populations enjoy benefits.

” alt=”Data center server infrastructure with cooling systems and power distribution in industrial facility”>

Electronic Waste and Lifecycle Impacts

The rapid obsolescence cycles of AI hardware generate enormous quantities of electronic waste containing toxic substances and valuable materials. When processors, memory chips, and networking equipment reach end-of-life, they typically enter informal recycling streams in developing nations where workers extract valuable metals using crude chemical processes. This informal recycling releases lead, mercury, cadmium, and other neurotoxins into soil and water systems, causing severe public health consequences.

Formal e-waste recycling, while more regulated, remains energy-intensive and incomplete. Separating mixed materials from complex circuit boards requires substantial electricity and generates hazardous byproducts. Many materials cannot be efficiently recovered, resulting in landfill disposal where they leach contaminants for decades. The circular economy for electronics remains aspirational rather than operational—most AI hardware components cannot be reused or recycled into new devices.

Lifecycle analysis of semiconductor production reveals that manufacturing represents 70-80% of total environmental impact, compared to 10-20% from operational energy consumption. This distribution has critical implications: even if AI companies transition entirely to renewable energy, the upstream environmental costs of hardware production remain massive. Extending device lifespans and optimizing efficiency becomes increasingly important than simply greening electricity sources.

The rapid advancement pace of AI technology creates perverse incentives toward planned obsolescence. Older processors cannot efficiently run newer algorithms, encouraging replacement cycles far shorter than hardware’s actual lifespan. Economic pressure to deploy latest-generation chips drives premature retirement of functioning equipment. This acceleration of hardware turnover multiplies all lifecycle environmental impacts—mining, manufacturing, transportation, and eventual waste generation.

AI Training: The Hidden Environmental Cost

Training large AI models concentrates enormous computational demand into specific periods, creating unique environmental challenges distinct from routine operational costs. A single training run of cutting-edge models can emit carbon equivalent to transatlantic flights for hundreds of people. As models grow larger and training datasets expand, these impacts escalate exponentially rather than linearly.

The economics of model training create perverse incentives. Researchers and companies face pressure to develop larger, more capable models to achieve competitive advantages. Each scaling increase multiplies training energy requirements substantially. The race for AI capability directly translates into accelerated environmental degradation, with no market mechanism capturing or pricing these externalities. Companies and researchers bear no financial consequences for environmental damage their training inflicts.

Redundancy in training processes multiplies impacts further. Multiple organizations train similar models independently, duplicating computational effort and environmental costs. Knowledge sharing remains limited due to competitive pressures and intellectual property concerns. This duplication represents enormous wasted resources—both economically and environmentally—with no offsetting benefits beyond individual organizational interests.

Infrastructure for training concentrates in specific geographic locations with abundant cheap electricity, often from fossil fuel sources. This geographic concentration means training emissions occur disproportionately in specific regions, creating local air quality degradation and community health impacts beyond global carbon accounting. Communities hosting training facilities bear environmental costs they did not choose and from which they derive minimal benefits.

Fine-tuning and adaptation training, while requiring less energy than initial model training, still consumes substantial resources. As organizations customize general models for specific applications, they perform additional training runs multiplying aggregate impacts. The proliferation of specialized AI models across sectors means total training-related emissions continue accelerating as adoption expands.

Ecosystem and Biodiversity Consequences

The cumulative environmental impacts of AI infrastructure cascade through ecosystems, degrading biodiversity and disrupting ecological functions that sustain all life. Water extraction for data center cooling directly reduces flows in rivers and streams, fragmenting aquatic habitats and preventing fish migration. Thermal pollution from cooling discharge alters water temperatures, eliminating habitat for temperature-sensitive species. These seemingly technical impacts translate into measurable species population declines and ecosystem dysfunction.

Mining operations for semiconductor materials destroy forests and grasslands, eliminating habitat for countless species while fragmenting remaining ecosystems into isolated patches. Large animals requiring extensive ranges find migration corridors severed; plant communities adapted to specific soil conditions cannot reestablish after mining reclamation. The recovery timelines for mined ecosystems extend across centuries, meaning current mining damage will constrain biodiversity for thousands of years.

Electrical generation infrastructure supporting AI data centers requires transmission lines crossing landscapes, altering wildlife movement patterns and fragmenting habitats. Renewable energy installations, while preferable to fossil fuels, still occupy substantial land areas and create habitat disruption. The scale of infrastructure required to power AI expansion means habitat loss accelerates substantially even with renewable energy transitions.

Atmospheric emissions from electricity generation and transportation across AI supply chains alter air quality, affecting plants’ photosynthetic efficiency and animal respiratory systems. Acid rain from coal-fired power plants damages forests and acidifies freshwater ecosystems. Particulate pollution reduces visibility and light penetration, disrupting photosynthesis and animal behavior patterns. These air quality impacts integrate across landscapes, creating diffuse but pervasive ecosystem stress.

The synergistic effects of multiple stressors create ecosystem vulnerability to collapse. Habitat fragmentation combined with pollution, water extraction, and climate change from AI-related emissions overwhelms ecosystems’ adaptive capacity. Species already stressed by climate change and human development find AI infrastructure as an additional pressure tipping them toward extinction. Biodiversity loss accelerates as ecosystems lack resilience to manage compounded threats.

Economic Externalities and Market Failures

The fundamental economic problem underlying AI’s environmental impact is that market prices fail to capture environmental costs. Companies deploying AI infrastructure pay for electricity, hardware, and labor, but not for the ecosystem damage, water depletion, or climate impacts their operations cause. This pricing failure creates economic incentives toward excessive AI deployment—from a private perspective, AI appears more beneficial than it actually is from a social perspective including environmental costs.

Environmental economists recognize this as a classic externality problem: costs borne by society and ecosystems are excluded from market prices, causing overproduction and overconsumption. The solution requires either internalizing externalities through carbon pricing, water fees, and mining impact assessments, or implementing regulatory constraints on environmental damage. Currently, neither mechanism effectively constrains AI’s environmental impact, allowing growth to continue despite substantial ecological costs.

UNEP research demonstrates that environmental accounting including externalities would substantially increase AI infrastructure costs, reducing profitable deployment scenarios. If companies paid true costs—including ecosystem restoration, water replacement, and climate damage—many proposed AI applications would prove economically unviable. Market failures enable deployment of technologies that destroy more value than they create when environmental impacts are properly valued.

The distribution of costs and benefits creates profound equity concerns. Wealthy nations and corporations benefit from AI capabilities while developing nations and poor communities bear disproportionate environmental costs through mining, water depletion, and pollution. This pattern replicates historical colonial extraction dynamics where resource-rich regions experience environmental devastation while distant populations enjoy benefits. Ecological economics frameworks emphasize that sustainable development requires equitable distribution of both benefits and environmental burdens.

Long-term economic impacts of ecosystem degradation from AI infrastructure will likely exceed short-term economic benefits from AI applications. Fisheries collapse, water scarcity, and biodiversity loss generate economic damages far exceeding computational benefits. Yet market mechanisms create incentives prioritizing immediate gains over long-term stability. Addressing this temporal mismatch requires policy interventions that make future environmental costs visible in present decision-making.

The Resource Society and ecological economics research emphasizes that infinite growth assumptions underlying current AI deployment are incompatible with finite planetary resources. As AI expands, environmental constraints will eventually bind, forcing either planned transition toward sustainable infrastructure or chaotic contraction when ecosystems collapse. Proactive policy design now could enable managed transition; continued inaction ensures painful adjustment later.

” alt=”Mountain landscape showing mining operations with exposed earth and deforestation alongside untouched forest ecosystem”>

Mitigation Strategies and Sustainable Solutions

Addressing AI’s environmental impact requires multifaceted approaches operating across technological, economic, and policy domains. No single solution suffices; rather, comprehensive strategies combining efficiency improvements, renewable energy transitions, supply chain transparency, and demand reduction offer pathways toward more sustainable AI infrastructure.

Technological efficiency improvements represent the most immediate intervention lever. Optimizing algorithms to require fewer computational operations, developing specialized hardware reducing energy per calculation, and improving data center cooling efficiency can reduce environmental impacts 30-50% without sacrificing capability. Research into neuromorphic computing and alternative architectures mimicking biological neural systems offers longer-term efficiency potential substantially exceeding current approaches. However, efficiency gains alone cannot offset exponential deployment growth—efficiency improvements must accompany absolute reduction in unnecessary AI applications.

Renewable energy transitions for data centers provide necessary but insufficient solutions. Powering AI infrastructure entirely from wind, solar, and hydroelectric sources eliminates operational carbon emissions. However, renewable energy transitions require substantial infrastructure investment, and renewable sources remain geographically concentrated. Additionally, renewable energy transitions address only 10-20% of AI’s total environmental impact; mining, manufacturing, and water consumption continue regardless of electricity sources. International Energy Agency analysis confirms that renewable energy alone cannot solve AI sustainability challenges without addressing demand and efficiency simultaneously.

Supply chain transparency and circular economy approaches can reduce mining impacts and waste generation. Requiring companies to audit and report environmental impacts of mineral sourcing, implementing extended producer responsibility making manufacturers liable for end-of-life waste, and developing genuine recycling infrastructure that recovers materials for reuse all contribute toward reducing lifecycle impacts. However, these approaches require regulatory enforcement and international cooperation that currently lacks political support.

Economic instruments internalizing environmental costs can align private incentives with social welfare. Carbon pricing on electricity used by data centers, water pricing reflecting scarcity and ecosystem impacts, and mining impact fees reflecting ecosystem restoration costs would increase AI infrastructure expenses, reducing deployment of marginally profitable applications. These mechanisms operate through market signals rather than mandates, potentially enabling more efficient resource allocation than prescriptive regulations.

Demand reduction represents the most challenging but potentially most impactful mitigation strategy. Not all proposed AI applications generate sufficient value to justify their environmental costs. Critically evaluating which AI deployments create genuine benefits versus which primarily serve corporate profit maximization could reduce infrastructure expansion substantially. This evaluation requires honest cost-benefit analysis including environmental impacts, something current market structures actively discourage.

Policy interventions establishing environmental impact assessment requirements for AI infrastructure deployment, implementing strict water usage limits in water-stressed regions, and requiring renewable energy for data centers represent regulatory approaches complementing market mechanisms. However, policy effectiveness requires international coordination, as companies can relocate infrastructure to jurisdictions with weaker environmental standards. Global frameworks similar to climate agreements could establish minimum environmental standards for AI infrastructure worldwide.

Transitioning toward reducing carbon footprint across technology sectors requires fundamental shifts in how societies value computational resources. Recognizing that environmental costs represent genuine economic costs, not externalities to ignore, enables rational decision-making about AI deployment. Education initiatives helping policymakers and business leaders understand AI’s true environmental impacts can drive demand for more sustainable alternatives and support for stronger environmental policies.

Research into alternative computational paradigms deserves substantial investment. Quantum computing, optical computing, and biological computing potentially offer dramatically improved efficiency compared to current silicon-based approaches. However, these technologies remain nascent, and their ultimate environmental profiles remain uncertain. Accelerating research while acknowledging that fundamental improvements may require decades positions societies for eventual transitions toward genuinely sustainable computation.

FAQ

What is the primary environmental impact of AI?

Energy consumption and resulting carbon emissions represent AI’s most significant quantified environmental impact, though water usage, mining impacts, and electronic waste collectively create substantial ecosystem damage. The cumulative effect of multiple stressors creates ecosystem stress exceeding impacts from any single source.

How much water does AI infrastructure consume?

Data centers supporting AI consume 0.5 to 1 liter of water per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated, translating to billions of gallons annually. In water-stressed regions, this extraction creates genuine resource conflicts with agricultural and municipal water needs.

Can renewable energy solve AI’s environmental problems?

Renewable energy addresses operational carbon emissions but represents only 10-20% of AI’s total environmental impact. Mining, manufacturing, and water consumption continue regardless of electricity sources. Renewable energy transitions are necessary but insufficient without accompanying efficiency improvements and demand reduction.

What minerals does AI infrastructure require?

Semiconductor production requires silicon, copper, aluminum, gold, tantalum, and cobalt. Rare earth elements extracted through environmentally destructive processes power AI applications. Mining these materials devastates ecosystems and displaces communities, particularly in developing nations.

How can individuals reduce AI’s environmental impact?

Supporting policies requiring environmental impact assessment for AI infrastructure, advocating for supply chain transparency, choosing products from companies with strong environmental commitments, and questioning whether specific AI applications justify their environmental costs all contribute toward systemic change. Additionally, renewable energy for homes and personal consumption reduction decrease overall demand for computational infrastructure.

What role do governments play in addressing AI’s environmental impact?

Governments can implement carbon pricing on data centers, establish water usage limits in water-stressed regions, require environmental impact assessments for infrastructure projects, and support research into more efficient computational approaches. International cooperation establishing minimum environmental standards for AI infrastructure worldwide represents a critical governance need.

Is AI deployment necessary despite environmental costs?

Some AI applications generate sufficient benefits to justify environmental impacts; others primarily serve corporate profit maximization without corresponding social value. Honest evaluation of whether specific applications create genuine benefits versus marginal enhancements in convenience requires transparent cost-benefit analysis including environmental externalities. Exploring environmental economics perspectives helps contextualize these tradeoffs.