Tillage’s Environmental Impact: Scientific Review

Conventional tillage practices have emerged as one of agriculture’s most environmentally damaging techniques, fundamentally altering soil structure, carbon cycles, and ecosystem health across millions of hectares globally. This comprehensive scientific review examines the multifaceted negative consequences of tillage agriculture, from soil degradation and carbon emissions to biodiversity loss and water contamination. Understanding these impacts is critical for policymakers, farmers, and environmental professionals seeking sustainable alternatives.

The practice of mechanically turning over soil, developed to control weeds and prepare seedbeds, has become a cornerstone of industrial agriculture. Yet mounting scientific evidence reveals that this routine operation triggers cascading environmental consequences that extend far beyond the farm gate, affecting atmospheric carbon concentrations, aquatic ecosystems, and the long-term viability of agricultural production itself.

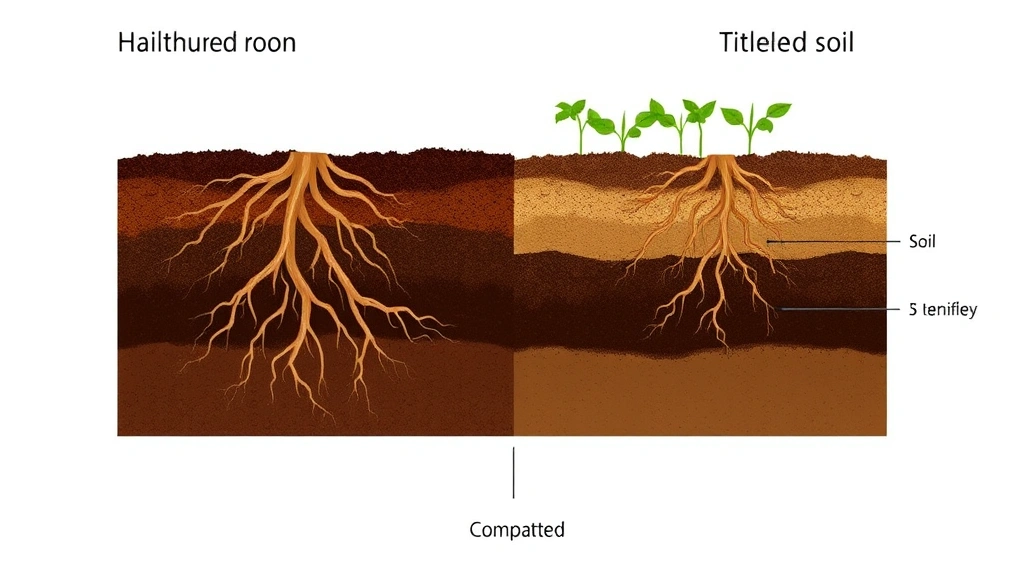

Soil Structure Degradation and Compaction

Tillage fundamentally destroys the complex soil architecture that develops over years through natural processes and biological activity. When plows, harrows, and cultivators mechanically disturb soil, they break apart soil aggregates—the stable clusters of soil particles held together by organic matter and microbial secretions. This disaggregation reduces soil porosity, water infiltration capacity, and aeration, creating conditions unfavorable for root penetration and microbial communities.

Repeated tillage operations, often conducted multiple times per growing season, progressively compact soil layers beneath the tilled zone, creating what soil scientists term a “hardpan” or “plow pan.” This impermeable layer restricts water movement and root development, reducing plant access to water and nutrients during critical growth periods. Research from agricultural extension services demonstrates that soils subjected to intensive tillage for 20+ years exhibit structural integrity comparable to compacted urban soils.

The loss of soil structure has cascading consequences for environmental science applications in agriculture. Degraded soil structure increases bulk density, reduces available water capacity, and diminishes the soil’s capacity to buffer against extreme weather events. Paradoxically, farmers often respond to these declining soil properties by increasing tillage frequency, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of degradation.

Carbon Emissions and Climate Impact

Perhaps the most significant climate-related impact of tillage involves the release of stored carbon dioxide from soil organic matter. Soils represent the largest terrestrial carbon reservoir, containing approximately 1,500 gigatons of carbon—more than double the amount in the atmosphere and vegetation combined. Tillage disrupts this carbon storage mechanism through multiple pathways.

When soil is inverted and aerated through mechanical disturbance, dormant organic matter becomes accessible to decomposing microorganisms. These microbes rapidly oxidize carbon compounds, releasing CO₂ to the atmosphere in a process that can continue for years after tillage events. Studies using stable isotope analysis have documented that a single deep plowing can release carbon accumulated over decades, with some estimates suggesting annual CO₂ losses of 200-500 kilograms per hectare in intensively tilled systems.

The carbon emissions from global tillage agriculture contribute significantly to atmospheric CO₂ concentrations. The World Bank estimates that agricultural soil management, dominated by tillage practices, accounts for approximately 5-10% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Converting from conventional tillage to conservation agriculture practices could sequester billions of tons of carbon annually, making soil carbon management critical for climate mitigation.

Additionally, tillage indirectly increases emissions through increased fossil fuel consumption. Tractor operations for multiple passes consume substantial diesel fuel, with annual fuel requirements for tillage-based systems reaching 20-40 liters per hectare. This energy cost, combined with the direct carbon loss from soil, creates a significant climate footprint for conventional agricultural practices.

Accelerated Soil Erosion

Tillage dramatically increases soil vulnerability to erosion by water and wind. Natural soil aggregates and protective organic matter layers that develop under undisturbed conditions provide mechanical resistance to erosive forces. Tilled soils, with their reduced aggregate stability and exposed surface, experience erosion rates 10-40 times higher than undisturbed soils under equivalent rainfall or wind conditions.

Water erosion represents the dominant erosion mechanism in humid and subhumid regions. When rainfall strikes exposed tilled soil, the impact energy breaks down remaining soil aggregates, creating a seal that reduces water infiltration and increases runoff. This runoff carries fine soil particles, creating the characteristic brown or reddish color of eroded sediment in streams and rivers. On moderate slopes, annual soil losses from tilled fields commonly exceed 10-20 tons per hectare—rates that cannot be sustained without progressive degradation.

Wind erosion becomes particularly severe in arid and semi-arid regions where vegetation cover is minimal and soil moisture is limited. The 1930s Dust Bowl catastrophe in North America demonstrated the catastrophic consequences of wind erosion from tilled soils, with massive dust storms removing the productive topsoil from millions of hectares. Modern examples from the Sahel region of Africa and the Inner Mongolia grasslands of China show that this problem persists despite nearly a century of soil conservation awareness.

Soil erosion represents an irreplaceable loss of natural capital. Soil formation rates under natural conditions typically range from 0.1 to 1 millimeter per year, while erosion rates from tilled soils commonly exceed 1-2 millimeters annually. This means that erosion rates exceed soil formation rates by 10-100 fold, creating a net loss of this critical resource. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that current erosion rates from agriculture will render 10 million hectares of land unproductive within the next 20 years if current trends continue.

Biodiversity Loss and Ecosystem Disruption

Tillage creates a hostile environment for soil biodiversity, eliminating habitats for the billions of organisms that inhabit healthy soils. Soil organisms—including bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, arthropods, and earthworms—provide critical ecosystem services including nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, water infiltration, and disease suppression.

The mechanical disturbance of tillage directly kills soil fauna, with studies documenting 30-70% reductions in earthworm populations immediately following plowing. These reductions persist because tillage eliminates the surface organic matter and stable soil structure that earthworms require for habitat and food. Earthworms are particularly important because they create continuous macropores that enhance water infiltration and aeration, and their casts improve soil aggregation and nutrient availability.

Fungal communities suffer disproportionately from tillage. Mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic associations with plant roots and enhance nutrient acquisition, require stable soil structure and continuous organic matter supply. Tillage fragments fungal networks and disrupts these beneficial associations. The loss of mycorrhizal fungi reduces plant stress tolerance and increases pathogenic fungal populations, creating conditions requiring increased pesticide applications.

Beyond soil organisms, tillage impacts above-ground biodiversity by eliminating habitat for ground-nesting birds, small mammals, and insects. Conventional tilled fields provide minimal cover or food resources, resulting in dramatically reduced biodiversity compared to environmental conditions in conservation agriculture or natural ecosystems. This biodiversity loss cascades through food webs, affecting pollinator populations, natural pest predators, and ecosystem resilience.

Water Quality Degradation

Tillage agriculture represents a major source of water pollution through multiple pathways. Accelerated erosion delivers sediment-bound nutrients and contaminants to waterways, while reduced water infiltration increases runoff carrying dissolved nutrients, pesticides, and pathogens. The cumulative effect is degradation of aquatic ecosystems and contamination of drinking water supplies.

Sediment from eroded tilled soils carries adsorbed phosphorus, a critical nutrient that becomes limiting in aquatic ecosystems. When phosphorus concentrations exceed natural levels, eutrophication results—excessive algal growth that depletes oxygen and creates dead zones. Major hypoxic zones in the Gulf of Mexico, Baltic Sea, and Black Sea are substantially attributable to nutrient runoff from tilled agricultural systems in their watersheds.

Pesticide and nitrogen fertilizer mobility increases dramatically in tilled systems due to reduced water infiltration and increased runoff. Reduced water infiltration means that applied chemicals remain on the soil surface longer, increasing their availability for transport in runoff. Simultaneously, the loss of vegetation and organic matter-rich soils reduces filtration and transformation of these contaminants. Nitrate contamination of groundwater from agricultural sources affects drinking water in numerous regions, with EPA data documenting widespread exceedances of safe drinking water standards in agricultural watersheds.

Pathogenic bacteria and viruses are also mobilized more readily in tilled systems with reduced water infiltration. E. coli and other pathogens from animal manure applications reach surface waters more quickly, increasing public health risks. The combination of sediment, nutrient, pesticide, and pathogen pollution from tilled agriculture creates complex water quality challenges requiring expensive treatment infrastructure.

Disrupted Nutrient Cycling

Healthy soils maintain nutrient cycling through complex biological and chemical processes that release nutrients from organic matter and mineral compounds in forms available to plants. Tillage disrupts these cycling mechanisms, creating dependency on external inputs and reducing soil fertility.

Organic matter decomposition, which releases nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients, proceeds more rapidly in tilled soils due to increased aeration and disruption of protective soil structures. This accelerated decomposition provides a temporary nutrient flush but depletes the organic matter reserves that sustain long-term fertility. Soils under continuous tillage lose 30-50% of their original organic matter content within 20-50 years, representing a massive loss of natural capital.

Mycorrhizal associations, which enhance plant nutrient acquisition efficiency, are disrupted by tillage. Plants relying on these fungal partners acquire nutrients more efficiently than plants dependent on root absorption alone. The loss of mycorrhizal function increases plant nutrient requirements and creates dependence on higher fertilizer applications. This not only increases production costs but also increases nutrient runoff and environmental contamination.

Nutrient stratification in tilled soils creates additional problems. Repeated surface tillage concentrates nutrients in shallow layers while deep soil layers become depleted. This creates uneven nutrient availability and increases leaching losses of mobile nutrients to groundwater. Long-term environmental sustainability requires restoring nutrient cycling mechanisms rather than increasing external inputs.

Economic and Agricultural Productivity Costs

While tillage was initially adopted to increase yields, the long-term economic consequences of soil degradation ultimately reduce agricultural productivity and profitability. The external costs of environmental damage—water treatment, ecosystem restoration, climate change mitigation—represent substantial economic burdens borne by society rather than the farmers implementing tillage.

Soil degradation reduces water-holding capacity, nutrient availability, and root penetration depth, decreasing plant-available water and nutrients during critical growth periods. This reduces yield potential and increases climate vulnerability, particularly important as extreme weather events become more frequent. Farmers compensate by increasing irrigation and fertilizer applications, driving up production costs and environmental impacts simultaneously.

The machinery and fuel costs of tillage are substantial, typically ranging from $50-100 per hectare annually depending on soil conditions and crop type. These direct costs, combined with reduced soil productivity, create economic pressure toward intensification and expansion rather than sustainable management. Alternative conservation agriculture systems often reduce input costs while improving long-term soil health, but require initial investment and management learning.

The economic analysis becomes more favorable for conservation approaches when environmental costs are internalized. Carbon pricing, water treatment costs, and ecosystem service valuations all increase the true cost of tillage agriculture. Economic research from agricultural and environmental institutes increasingly demonstrates that conservation agriculture delivers superior economic returns when all costs and benefits are considered over multi-decade timeframes.

Conservation Agriculture Solutions

Scientific research has identified multiple conservation agriculture approaches that maintain or enhance productivity while eliminating tillage’s negative impacts. These systems share three core principles: minimal soil disturbance, permanent soil cover, and crop diversification.

No-till systems eliminate mechanical soil disturbance entirely, instead using herbicides for weed management and direct seeding into previous crop residues. No-till farming preserves soil structure, maintains organic matter, sequesters carbon, and dramatically reduces erosion. Global adoption has expanded to over 100 million hectares, with documented yield maintenance or increases alongside reduced input costs and improved environmental outcomes.

Conservation tillage represents an intermediate approach, retaining significant crop residues on the surface while reducing the intensity and depth of mechanical disturbance. This approach maintains some benefits of tillage for specific weed or disease management while reducing overall environmental impacts. Residue retention is critical, as exposed soil remains vulnerable to erosion and carbon loss.

Crop rotation and diversification enhance conservation agriculture effectiveness by providing natural weed and pest management, reducing chemical inputs, and improving soil biological activity. Legume crops fix atmospheric nitrogen, reducing synthetic fertilizer requirements. Diverse crop rotations support more diverse soil communities and create more resilient agricultural systems.

Transition to conservation agriculture requires management adjustment and often involves temporary yield reductions as soil biological communities rebuild. However, multi-year studies consistently document that after 3-5 years, conservation agriculture systems match or exceed tilled system yields while delivering substantial environmental and economic benefits.

FAQ

What exactly is tillage and why was it developed?

Tillage refers to mechanical disturbance of soil, historically developed to control weeds, incorporate organic matter, and prepare seedbeds for planting. Before herbicides, mechanical weed control was the primary management tool available. Modern industrial agriculture inherited this practice despite the availability of alternative weed management approaches.

How much carbon does tillage actually release?

Annual carbon losses from global tillage agriculture range from 0.4 to 1.2 gigatons of CO₂ equivalent, depending on soil type, climate, and tillage intensity. Converting the world’s tilled cropland to conservation agriculture could sequester 0.5-1.0 gigatons annually, making soil management a critical climate solution.

Can farmers transition to no-till farming without losing yields?

Yes, extensive research demonstrates that no-till systems maintain or increase yields within 3-5 years of implementation. Initial transition challenges relate to weed management and pest control adjustments, but these can be addressed through integrated pest management strategies. The key is managing the transition period strategically rather than abandoning conservation agriculture due to short-term challenges.

Is conservation agriculture economically viable for small-scale farmers?

Conservation agriculture is particularly beneficial for small-scale farmers in developing regions, as it reduces input costs, decreases labor requirements, and improves resilience to climate variability. However, successful adoption requires access to appropriate equipment, training, and market access. Development programs have successfully supported transitions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

What are the main barriers to wider adoption of conservation agriculture?

Key barriers include farmer familiarity with tillage practices, availability of appropriate herbicides and equipment, knowledge gaps regarding transition management, and lack of policy support in some regions. Additionally, commodity price structures and subsidy programs often favor input-intensive conventional systems, creating economic disincentives for conservation adoption.