Understanding EIA Reports: Expert Insights into Environmental Impact Assessment

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports represent a critical intersection between economic development and ecological preservation. These comprehensive documents evaluate the potential consequences of proposed projects on natural systems, communities, and long-term sustainability. As governments and organizations increasingly recognize the economic value of ecosystem services, understanding EIA reports has become essential for policymakers, investors, and environmental professionals seeking to balance growth with responsible stewardship.

The sophistication of modern EIA reports reflects decades of scientific advancement and regulatory evolution. From infrastructure megaprojects to industrial facilities, these assessments provide the empirical foundation for informed decision-making. This guide explores the architecture, methodologies, and real-world applications of environmental impact assessment reports through an economic ecology lens.

What is an Environmental Impact Assessment Report?

An environmental impact assessment report is a formal document that systematically evaluates the potential environmental, social, and economic consequences of a proposed project or development activity. These reports serve as decision-support tools, enabling authorities to understand trade-offs between economic benefits and ecological costs. The United Nations Environment Programme recognizes EIA as a fundamental instrument for sustainable development planning.

At its core, an EIA report addresses fundamental questions: What will this project do to the environment? Who will be affected? What alternatives exist? Can negative impacts be mitigated? The comprehensiveness of these assessments distinguishes them from simpler environmental checklists, providing depth necessary for complex infrastructure and industrial projects.

The scope of EIA reports extends beyond simple pollution metrics. Modern assessments integrate biodiversity considerations, climate resilience, ecosystem service valuations, and cumulative impact analysis. This holistic approach recognizes that environmental science requires understanding interconnected systems rather than isolated environmental factors.

Historical Development and Regulatory Framework

The modern EIA framework emerged from the United States National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969, which mandated environmental review for federal projects. This pioneering legislation recognized that environmental consequences deserved systematic analysis before project approval. The success of NEPA inspired global adoption, with over 100 countries now requiring EIA reports for major developments.

The regulatory evolution reflects growing recognition of environmental economics principles. Early assessments focused narrowly on pollution; contemporary frameworks incorporate ecosystem service valuation, climate impact quantification, and long-term sustainability metrics. International standards, developed through organizations like the World Bank, have created convergence around best practices, though significant regional variations persist.

Key regulatory milestones include the 1985 European Union EIA Directive, which established minimum assessment standards across member states, and the Aarhus Convention’s emphasis on public participation rights. These frameworks embedded the principle that environmental decision-making should be transparent and inclusive, recognizing that informed public discourse on environmental issues strengthens policy outcomes.

Core Components of EIA Reports

A comprehensive EIA report typically contains several essential sections, each serving specific analytical purposes:

- Executive Summary: Distilled findings accessible to non-technical audiences, enabling informed public participation and policy review

- Project Description: Detailed specifications of proposed activities, locations, timelines, and resource requirements

- Baseline Environmental Conditions: Characterization of existing ecosystems, species, air quality, water resources, and socioeconomic conditions

- Impact Prediction: Quantified or qualitative assessment of how project activities will alter environmental conditions

- Mitigation Measures: Specific actions to reduce negative impacts, including design modifications, operational controls, and restoration commitments

- Alternatives Analysis: Evaluation of alternative project designs, locations, or technologies with different environmental profiles

- Monitoring and Management Plans: Frameworks for tracking actual impacts and implementing adaptive management responses

- Cumulative Impact Assessment: Analysis of combined effects from multiple projects and ongoing activities in the region

The environmental file documentation supporting these sections often comprises thousands of pages of technical appendices, scientific studies, and stakeholder comments. This depth enables rigorous review and accountability.

Methodologies and Assessment Techniques

EIA practitioners employ diverse methodologies tailored to project characteristics and environmental contexts. Quantitative approaches dominate technical sections, utilizing modeling software to predict impacts on air dispersion, water quality, noise propagation, and ecological communities. These models integrate site-specific data with established scientific relationships, producing testable predictions.

Qualitative assessment methods complement quantitative analysis, particularly for complex socioeconomic impacts and ecosystem services difficult to monetize. Expert judgment, informed by peer-reviewed literature and professional experience, structures evaluation of impacts like visual aesthetics, cultural heritage disruption, and community cohesion effects.

Geographic information systems (GIS) have revolutionized spatial analysis within EIA reports, enabling visualization of sensitive habitats, vulnerable populations, and cumulative stressors. Habitat mapping combined with species distribution models allows assessment of impacts on biodiversity, while demographic mapping identifies communities facing disproportionate burdens.

Scenario analysis represents another critical methodology, exploring how different project designs, operational parameters, or environmental conditions would alter impact profiles. This analytical flexibility supports adaptive management, allowing decision-makers to select approaches that minimize environmental consequences while maintaining project viability.

Image Placeholder 2: Environmental assessment field work with ecological monitoring equipment

Economic Valuation of Environmental Impacts

Contemporary EIA reports increasingly incorporate economic valuation of environmental impacts, translating ecological consequences into comparable monetary terms. This approach, rooted in ecological economics research, enables more transparent comparison of project benefits and environmental costs.

Valuation methodologies include market-based approaches (using observed prices for environmental goods like timber or fishery products), revealed preference methods (inferring environmental values from actual behavior patterns), and stated preference approaches (surveying individuals about their willingness to pay for environmental protection). Each methodology carries specific assumptions and limitations, requiring transparent disclosure of valuation choices.

The challenge of ecosystem service valuation lies in quantifying services like climate regulation, pollination, water filtration, and cultural significance. These services provide substantial economic benefits—global ecosystem services are estimated at trillions of dollars annually—yet often lack clear market signals. EIA reports addressing this valuation gap provide more complete accounting of project trade-offs.

Discount rate selection significantly influences how EIA reports value future environmental consequences. Higher discount rates minimize the present cost of long-term environmental degradation, potentially undervaluing impacts on future generations. Conversely, lower rates emphasize intergenerational equity but may reduce project feasibility. This analytical choice reflects fundamental values about sustainability and justice.

Stakeholder Engagement and Public Participation

Effective EIA processes integrate meaningful stakeholder engagement, recognizing that affected communities possess valuable knowledge and legitimate interests in development decisions. Public participation ranges from information disclosure to collaborative decision-making, with regulatory requirements varying by jurisdiction.

Early engagement with indigenous communities, local governments, and environmental organizations strengthens EIA quality by incorporating diverse perspectives on environmental values and vulnerability. Communities often identify impacts that technical specialists might overlook—for example, traditional ecological knowledge may reveal seasonal patterns or species behaviors not captured in scientific literature.

The challenge of equitable participation persists in many EIA processes, particularly in developing regions where disadvantaged populations lack resources to engage meaningfully. Language barriers, limited access to technical information, and power imbalances can undermine the participatory ideal. Addressing these constraints requires dedicated resources for community capacity-building and transparent information provision.

Digital platforms increasingly facilitate public participation, enabling broader comment submission and real-time information access. However, digital divides may exclude populations lacking internet connectivity or technological literacy, potentially exacerbating existing inequities in environmental decision-making.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their importance, EIA reports face significant methodological and institutional challenges. Predicting environmental impacts with precision remains difficult, particularly for complex ecological systems with nonlinear dynamics and thresholds. Climate change introduces additional uncertainty, as historical environmental conditions may not predict future states, undermining baseline characterization and impact projection validity.

Time constraints often compromise EIA quality, with compressed review periods limiting the comprehensiveness possible for complex projects. Regulatory timelines, typically measured in months, prove insufficient for rigorous impact prediction and mitigation design, particularly when addressing cumulative impacts across large geographic areas.

Institutional capacity limitations affect EIA implementation globally. Developing countries often lack technical expertise, funding, and enforcement mechanisms necessary for rigorous assessment. This capacity gap can result in superficial reviews that fail to identify significant impacts or inadequate mitigation commitments. Addressing this challenge requires international technical assistance and knowledge transfer.

The carbon footprint quantification approaches increasingly incorporated into EIA reports highlight how assessment methodologies continue evolving. Climate impact assessment, once peripheral to EIA, now represents a central concern as the urgency of climate mitigation becomes apparent.

Mitigation effectiveness presents another challenge—EIA reports specify mitigation measures, but actual implementation and effectiveness monitoring often prove inadequate. Post-project auditing, which would verify whether predicted impacts materialized and whether mitigation measures functioned as designed, remains inconsistently applied globally.

Real-World Case Studies

Examining specific EIA reports illuminates how assessment frameworks address diverse project types and environmental contexts. Large infrastructure projects like dams, highways, and ports generate voluminous EIA documentation addressing impacts on water resources, terrestrial ecosystems, fisheries, and communities.

The Three Gorges Dam environmental impact assessment in China exemplified both the potential and limitations of large-scale EIA. The report identified numerous impacts including habitat loss, species extinction risk, and community displacement. Yet post-construction monitoring revealed that some predicted impacts differed from actual consequences, highlighting the inherent uncertainty in predicting complex ecological responses.

Renewable energy projects, including wind and solar facilities, generate growing numbers of EIA reports addressing different impact profiles than fossil fuel infrastructure. These assessments focus on habitat fragmentation, bird and bat mortality, visual landscape change, and noise impacts. The comparative advantage of renewable projects from climate perspectives must be balanced against site-specific ecological consequences, a trade-off analysis increasingly prominent in contemporary EIA reports.

Mining operations produce among the most complex EIA reports, addressing water contamination, habitat destruction, tailings storage risks, and acid mine drainage spanning decades post-closure. These assessments grapple with long-term liability and irreversible ecosystem changes, raising fundamental questions about whether economic benefits justify permanent environmental transformation.

Agricultural intensification projects illustrate how EIA principles extend beyond industrial infrastructure. Assessment of large-scale agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa addresses soil degradation, water resource depletion, agrochemical pollution, and biodiversity loss from habitat conversion. These reports increasingly incorporate climate resilience and food security considerations alongside traditional environmental metrics.

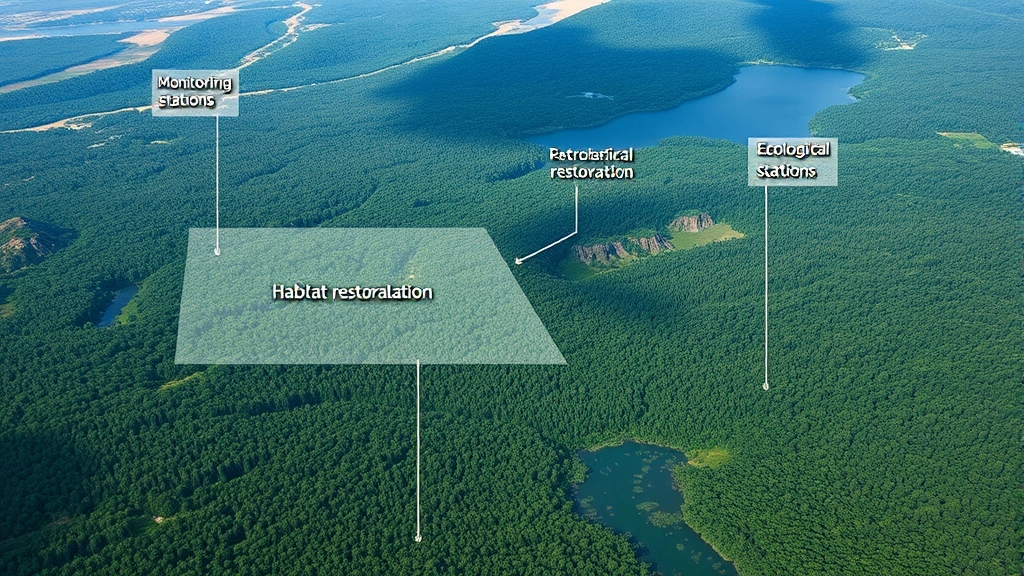

Image Placeholder 3: Landscape showing ecosystem monitoring stations and environmental assessment infrastructure

The renewable energy transition itself generates new EIA demands, as renewable energy infrastructure deployment accelerates globally. Large-scale solar and wind projects require rigorous environmental assessment, balancing climate benefits against site-specific ecological consequences. This emerging challenge demonstrates how EIA frameworks must continuously adapt to changing development priorities.

Future Directions and Emerging Frameworks

EIA practice continues evolving in response to emerging environmental challenges and methodological advances. Climate change integration represents a major frontier, with frameworks now requiring assessment of project vulnerability to climate impacts and project contributions to greenhouse gas emissions. This integration recognizes that environmental assessment must address both mitigation and adaptation imperatives.

Biodiversity assessment sophistication has increased substantially, incorporating ecosystem service valuation, habitat connectivity analysis, and species-specific vulnerability assessment. The recognition that sustainability extends across economic sectors including fashion and consumption illustrates how EIA principles increasingly penetrate non-traditional development domains.

Cumulative impact assessment represents another frontier, moving beyond individual project analysis toward landscape-scale understanding of combined stressors. This approach recognizes that ecosystem resilience depends on total environmental burden, not individual project impacts. Implementation requires coordination across projects and jurisdictions, presenting institutional coordination challenges.

Nature-based solutions increasingly feature in EIA mitigation sections, reflecting growing recognition that ecological restoration can simultaneously address environmental impacts and provide co-benefits including carbon sequestration, water purification, and community livelihood support. This integration of mitigation with ecosystem restoration represents a significant evolution from earlier approaches focused on pollution control alone.

The UNEP guidance on environmental impact assessment continues advancing international best practices, emphasizing adaptive management, strategic environmental assessment (SEA) integration, and enhanced stakeholder participation. These frameworks reflect recognition that EIA effectiveness depends on institutional commitment and adequate resourcing.

FAQ

What is the primary purpose of an environmental impact assessment report?

EIA reports provide systematic evaluation of potential environmental, social, and economic consequences of proposed projects. They enable informed decision-making by quantifying impacts, identifying mitigation opportunities, and comparing alternatives—fundamentally supporting sustainable development by making environmental trade-offs explicit and transparent.

How long does it typically take to prepare an EIA report?

EIA preparation timelines vary substantially based on project complexity, environmental sensitivity, and data availability. Simple projects may require 3-6 months, while complex infrastructure or industrial projects frequently require 12-24 months or longer. Time constraints often compromise assessment quality, particularly for addressing cumulative impacts and long-term consequences.

Who prepares environmental impact assessment reports?

Interdisciplinary teams typically prepare EIA reports, including environmental scientists, engineers, economists, social scientists, and specialists in specific disciplines like hydrogeology or wildlife biology. Project proponents usually commission reports, though independent review by regulatory agencies or third-party auditors adds credibility. This funding structure raises potential bias concerns, leading some jurisdictions to require independent verification.

Can projects be approved despite significant negative environmental impacts identified in EIA reports?

Yes, projects can proceed with identified impacts if decision-makers determine that benefits justify consequences and adequate mitigation measures are implemented. This discretionary authority, while enabling necessary development, creates accountability challenges. Transparent decision-making frameworks and clear mitigation commitments help ensure that identified impacts receive appropriate consideration.

How do EIA reports address climate change impacts?

Contemporary EIA reports increasingly assess both how projects will be vulnerable to climate change and how projects will contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. This dual perspective recognizes that development must address climate mitigation while building resilience to unavoidable climate changes. Quantifying carbon footprints and evaluating climate adaptation measures now represent standard EIA components.

What happens after an EIA report is approved?

Post-approval implementation includes monitoring actual environmental conditions against predictions, implementing mitigation measures as specified, and conducting periodic audits of effectiveness. Adaptive management frameworks allow adjusting mitigation approaches if monitoring reveals that impacts differ from predictions. Unfortunately, post-project auditing remains inconsistently applied globally, limiting accountability for EIA accuracy.