Navigating a VUCA World: Economist Insights on Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity

The global economy operates within an increasingly unpredictable landscape characterized by rapid technological disruption, climate volatility, geopolitical tensions, and interconnected financial systems. This environment—known as VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity)—presents profound challenges for economists, policymakers, and organizations attempting to forecast trends and develop sustainable strategies. Understanding how economic systems respond to VUCA conditions is essential for building resilience in both developed and developing economies, particularly as environmental pressures compound traditional market uncertainties.

Economists today face unprecedented analytical demands. Traditional models built on historical data patterns struggle when faced with black swan events, cascading supply chain disruptions, and climate-induced economic shocks. The intersection of ecological limits and economic growth—a central concern in ecological economics—reveals that VUCA environments are not merely temporary disruptions but potentially structural features of an economy approaching planetary boundaries. This article explores how economists interpret and navigate VUCA conditions while integrating ecological considerations into strategic planning and policy recommendations.

Understanding VUCA in Economic Context

VUCA emerged from military strategy literature in the 1990s and has become increasingly relevant to economic analysis. Volatility refers to rapid, often unexpected price fluctuations and market movements. Uncertainty describes situations where outcomes cannot be predicted from historical data. Complexity involves numerous interconnected variables that produce non-linear effects. Ambiguity exists when multiple interpretations of the same data lead to conflicting conclusions about causation and appropriate responses.

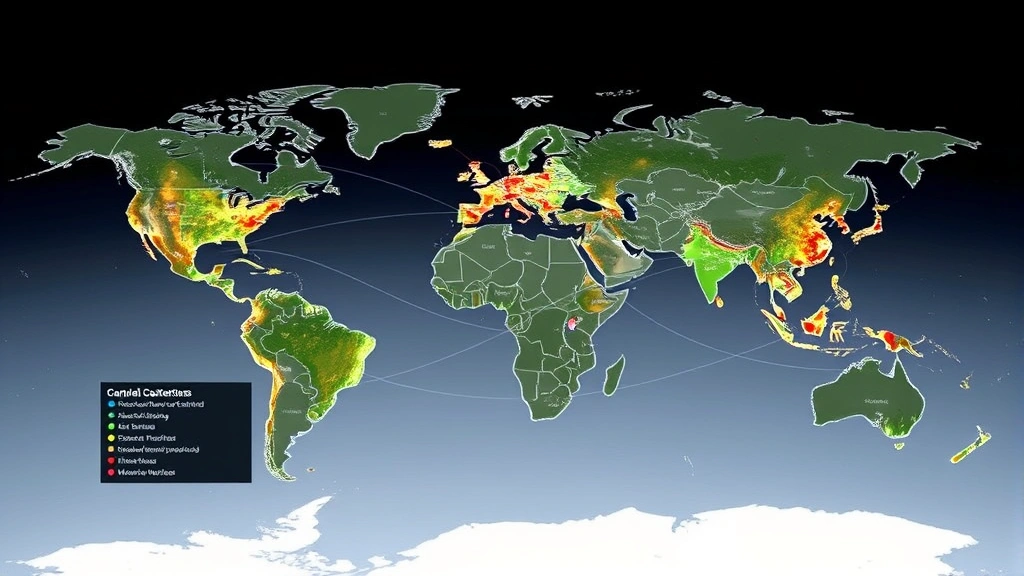

For economists studying environmental systems, VUCA conditions represent a fundamental shift from the stable equilibrium assumptions embedded in classical economic theory. When you examine economic analysis through an ecological lens, VUCA becomes not an anomaly but a predictable consequence of operating within planetary boundaries. The World Bank has documented how climate volatility alone introduces 2-3 percentage point variations in agricultural productivity across regions, cascading into broader economic instability.

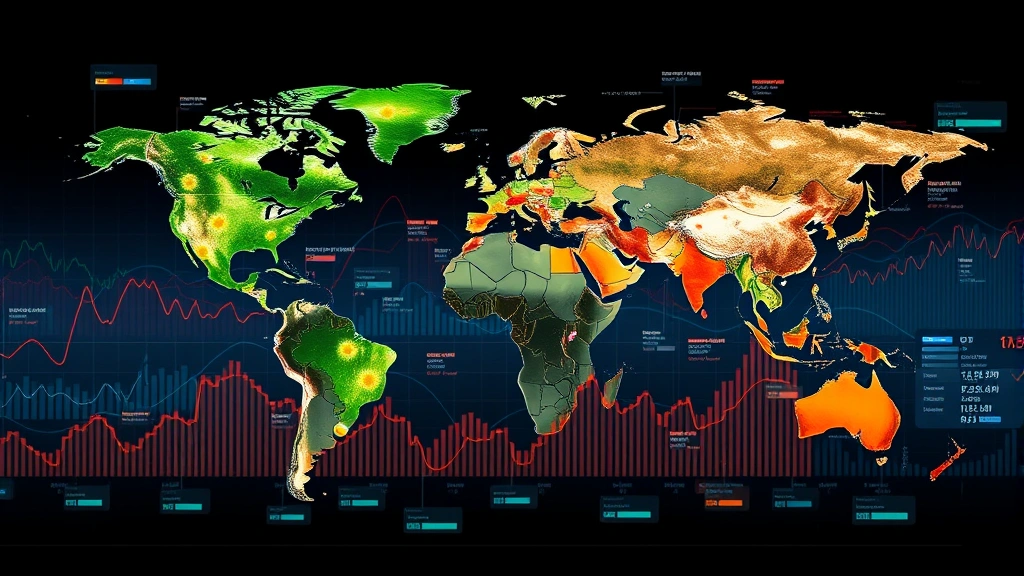

Contemporary VUCA environments stem from multiple reinforcing factors: supply chain globalization creates systemic vulnerability, financial markets respond to sentiment as much as fundamentals, climate systems exhibit tipping point behavior, and technological disruption accelerates unpredictably. Economists must simultaneously track commodity price volatility, currency fluctuations, policy uncertainty indices, and environmental indicators to construct meaningful forecasts.

Volatility: Market Swings and Environmental Shocks

Market volatility has increased measurably over the past two decades. The VIX (volatility index) shows that financial markets experience more frequent and sharper swings than historical averages suggested. However, environmental volatility—manifested through extreme weather events, water availability fluctuations, and crop yield variations—increasingly drives macroeconomic volatility in ways traditional models underestimate.

Consider agricultural economics: a severe drought in a major grain-producing region creates immediate price spikes affecting global food security, which triggers currency movements, inflation adjustments, and policy responses across multiple economies. The 2010-2012 global food crisis demonstrated how environmental volatility translates directly into economic volatility, affecting social stability and political outcomes. Economists analyzing this period found that price volatility for staple crops correlated more strongly with extreme weather patterns than with traditional supply-demand fundamentals.

Energy markets exhibit similar patterns. Oil price volatility stems not only from geopolitical events but increasingly from energy transition dynamics—renewable energy capacity additions create supply-side shocks, while policy announcements about carbon pricing or fossil fuel phase-outs introduce demand-side uncertainty. Economists must now model both traditional market volatility and environmental constraint volatility simultaneously, requiring integration of climate science data into economic forecasting.

The relationship between volatility and environmental awareness creates feedback loops. As stakeholders recognize climate risks, capital allocation becomes more reactive, amplifying market swings. Insurance markets, crucial for absorbing volatility, face difficulty pricing risks when historical data no longer predicts future climate patterns—a problem that undermines one of capitalism’s core risk-management mechanisms.

Uncertainty and Ecological Tipping Points

Uncertainty in economics traditionally refers to incomplete information about future states. However, ecological uncertainty introduces a qualitatively different dimension: the possibility of irreversible system transitions beyond which recovery becomes impossible or prohibitively expensive. When economists confront uncertainty about whether current emissions trajectories will trigger irreversible climate tipping points, they face fundamentally different decision-making challenges than traditional uncertainty analysis accommodates.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identifies multiple potential tipping points: Amazon rainforest dieback, Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation collapse, Greenland ice sheet disintegration, and West Antarctic ice sheet destabilization. Economic models incorporating these possibilities must assign probabilities to outcomes with potentially catastrophic consequences—a task that stretches conventional cost-benefit analysis beyond its methodological limits.

UNEP research demonstrates that uncertainty about ecosystem service valuation creates systematic underestimation of environmental risks in economic planning. Freshwater aquifer depletion, pollinator population collapse, and ocean acidification all present deep uncertainty—we know directional trends but face substantial uncertainty about timing, magnitude, and economic consequences of system transitions.

Economists increasingly adopt precautionary approaches when facing deep uncertainty about ecological tipping points. This represents a significant departure from expected utility maximization, instead emphasizing strategies that maintain optionality and avoid irreversible decisions. Reducing carbon footprint becomes not merely an environmental imperative but an economic decision under deep uncertainty—investing in emissions reductions represents insurance against catastrophic outcomes.

Complexity in Interconnected Systems

Economic complexity has expanded dramatically as global supply chains have deepened and financial systems have become more interconnected. A disruption at one point—whether a semiconductor shortage, port closure, or financial institution failure—cascades through multiple sectors with unpredictable intensity and timing.

The 2020 pandemic revealed this complexity starkly. Initial lockdowns in China created supply chain disruptions that propagated globally, affecting industries with no direct exposure to pandemic-affected regions. Simultaneously, fiscal stimulus created demand-side pressures while supply-side constraints persisted, producing inflation dynamics that confounded traditional Phillips Curve relationships. Complexity manifested as the inability to isolate single causes for observed outcomes—inflation resulted from simultaneous supply constraints, demand stimulus, energy price shocks, and labor market tightness, with economists disagreeing substantially about causal weights.

Environmental complexity compounds economic complexity. Water stress affects agricultural productivity, which affects food prices, which affects consumer spending, which affects labor demand, which affects migration patterns, which affects housing markets, which affects financial stability. These linkages create system-wide vulnerability where environmental degradation in one region generates economic effects globally.

Network analysis reveals that supply chain complexity creates systemic risk concentration. When multiple industries depend on the same specialized suppliers—as occurs with rare earth elements, semiconductor manufacturing, or pharmaceutical inputs—system-wide disruption becomes possible from single-point failures. Economists must now evaluate resilience not merely through financial metrics but through supply chain topology analysis.

Ambiguity and Policy Response Mechanisms

Ambiguity—multiple plausible interpretations of identical data—presents unique challenges for policymakers. When economists disagree about whether inflation results from demand excess or supply constraints, policy responses diverge dramatically. Demand-focused analysis suggests monetary tightening; supply-focused analysis suggests targeted supply-side interventions. When ambiguity persists, policies often address multiple interpretations simultaneously, creating potentially contradictory effects.

Environmental policy faces profound ambiguity. Should carbon pricing mechanisms emphasize permit allocation or carbon tax design? Should climate policy prioritize emissions reduction or adaptation investment? Should renewable energy deployment follow market-driven or centrally-planned approaches? Each interpretation of climate economics leads to different policy recommendations, yet ambiguity about which interpretation proves correct persists.

The relationship between economic growth and environmental impact exhibits ambiguity that complicates policy. Decoupling theory suggests economic growth can continue while environmental impact declines through efficiency improvements and structural change. However, empirical evidence remains ambiguous—some economies show relative decoupling (growth faster than environmental impact growth) but absolute decoupling (actual environmental impact decline) remains rare at global scales. This ambiguity creates policy paralysis where growth-focused and environmental-focused advocates interpret identical data as supporting their preferred approaches.

Economists increasingly recognize that ambiguity cannot be resolved through additional data collection alone—fundamental interpretive disagreements reflect different theoretical frameworks and value assumptions. Robust policymaking under ambiguity requires strategies that perform reasonably well across multiple plausible interpretations rather than betting on single interpretations proving correct.

Strategies for Economic Resilience

Navigating VUCA environments requires deliberate resilience-building strategies. Diversification across suppliers, markets, and energy sources reduces vulnerability to single-point failures. Redundancy—maintaining excess capacity and multiple options—proves expensive in normal times but essential when disruptions occur. Flexibility—ability to rapidly adjust production, sourcing, or operations—becomes valuable when future conditions remain uncertain.

For organizations, VUCA resilience involves scenario planning that explicitly incorporates environmental variables alongside traditional business scenarios. Rather than assuming stable climate and environmental conditions, resilient strategies must perform adequately across multiple climate futures. Renewable energy adoption exemplifies this approach—investment in solar and wind capacity provides resilience against fossil fuel price volatility and supply disruption while hedging against climate policy changes.

For national economies, resilience requires building institutional capacity for rapid policy adjustment. Economies that can quickly reallocate resources, adjust regulations, and mobilize investment when disruptions occur demonstrate superior VUCA navigation. This contrasts with rigid institutional structures optimized for stable conditions. Successful VUCA navigation often involves maintaining what economists call “adaptive capacity”—the ability to learn from disruptions and modify strategies accordingly.

Financial system resilience proves particularly critical. When volatility increases and uncertainty deepens, financial systems must absorb shocks without amplifying them. Stronger capital requirements, reduced leverage, and more conservative risk management frameworks reduce systemic fragility. However, these measures involve trade-offs with financial efficiency and growth potential—resilience requires accepting lower returns in normal times to prevent catastrophic losses in disruption scenarios.

Technology and Innovation as Stabilizers

Technology presents paradoxical relationships with VUCA. Technological disruption creates volatility and uncertainty as existing business models become obsolete and competitive dynamics shift. However, technology also provides tools for managing VUCA conditions through improved information, more sophisticated modeling, and enhanced adaptability.

Data analytics and artificial intelligence enable more sophisticated risk identification and scenario analysis. Real-time supply chain visibility allows organizations to detect disruptions earlier and respond more rapidly. Advanced weather forecasting and climate modeling improve economic planning under environmental uncertainty. However, these technologies introduce their own complexities—AI systems trained on historical data may fail catastrophically when facing novel conditions, and increased data availability can paradoxically increase ambiguity by enabling multiple plausible interpretations.

Renewable energy technology exemplifies how innovation addresses VUCA. Solar and wind power, combined with battery storage and smart grid technology, provide energy system resilience against fossil fuel supply disruptions and price volatility. Distributed renewable generation reduces dependence on centralized infrastructure vulnerable to single-point failures. However, renewable energy integration introduces new complexities requiring sophisticated grid management and storage solutions.

Biotechnology offers tools for agricultural resilience under climate volatility—drought-resistant crop varieties, precision agriculture techniques, and alternative protein production methods all reduce vulnerability to environmental shocks. However, technological solutions create new dependencies and introduce moral hazard where adaptation investment declines in response to perceived technological fixes.

The most effective VUCA navigation combines technological innovation with institutional adaptation and behavioral change. Technology alone cannot resolve ambiguity about appropriate policies, nor can it eliminate fundamental trade-offs between efficiency and resilience. Successful navigation requires integrating technological capability with adaptive governance structures and stakeholder engagement processes that build consensus around appropriate responses to multiple plausible futures.

” alt=”Digital visualization of interconnected global supply chains with nodes representing manufacturing hubs, distribution centers, and markets, showing vulnerability points where disruptions cascade through networks, with environmental stress indicators overlaid”>

Integrating Ecological Economics into VUCA Analysis

Conventional economic analysis often treats environmental variables as externalities—costs or benefits not reflected in market prices. However, ecological economics recognizes environmental systems as fundamental economic constraints rather than peripheral concerns. This reframing proves essential for VUCA analysis because it identifies environmental limits as potential sources of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

When economists integrate environmental perspectives into VUCA frameworks, they recognize that resource depletion, ecosystem degradation, and planetary boundary transgression create structural economic constraints. Soil degradation reduces agricultural productivity growth rates; freshwater depletion increases production costs; biodiversity loss reduces ecosystem service provision; ocean acidification affects fishery productivity. These environmental changes introduce both direct economic volatility and deeper uncertainty about sustainable economic models.

The concept of “natural capital” proves useful for VUCA analysis. Just as financial capital requires maintenance and investment to generate returns, natural capital requires stewardship to maintain productive capacity. Economies that deplete natural capital—harvesting forests faster than regeneration, extracting groundwater faster than recharge, fishing faster than reproduction—create future volatility and uncertainty through declining resource availability and rising production costs.

Ecological economics also emphasizes threshold and tipping point dynamics absent from conventional economic models. Ecosystems often exhibit non-linear responses where gradual degradation produces stable outcomes until a threshold is crossed, after which rapid collapse occurs. This creates ambiguity about current sustainability—systems may appear stable while approaching critical thresholds. Economic models must incorporate these ecological dynamics to accurately assess VUCA conditions.

Global Perspectives on VUCA Navigation

Different regions face distinct VUCA challenges based on economic structure, institutional capacity, and environmental vulnerability. Developing economies often experience greater volatility due to dependence on commodity exports, limited institutional capacity for rapid policy adjustment, and heightened climate vulnerability. Developed economies face different challenges: complex financial systems prone to cascade failures, technological disruption threatening established industries, and energy system transition requirements.

According to IMF research, emerging markets face particular VUCA challenges from capital flow volatility—when global risk appetite declines, capital rapidly exits emerging markets, creating currency crises and financial instability independent of domestic economic fundamentals. This amplifies domestic policy uncertainty and constrains options for addressing economic challenges.

The transition to renewable energy creates distinct VUCA challenges by region. Economies dependent on fossil fuel exports face demand destruction and transition costs; economies dependent on fossil fuel imports face supply disruption risks; economies attempting rapid renewable deployment face technology cost volatility and integration challenges. No single approach suits all contexts, requiring adaptive strategies tailored to specific vulnerabilities.

International cooperation proves essential for VUCA navigation when challenges transcend borders. Climate change, pandemic disease, financial contagion, and supply chain disruption all require coordinated responses. However, international cooperation faces ambiguity about burden-sharing, conflicting national interests, and institutional coordination challenges. Economists must understand both the technical requirements for effective responses and the political economy of achieving international coordination.

” alt=”Aerial view of diverse landscapes showing industrial facilities, agricultural regions, renewable energy installations, and natural ecosystems in geographic proximity, illustrating the interconnection between economic activity and environmental systems in a complex integrated landscape”>

Practical Frameworks for Decision-Making Under VUCA

Economists and policymakers employ several frameworks for navigating VUCA conditions. Scenario analysis develops multiple plausible futures and evaluates strategies across scenarios rather than betting on single forecasts. Robust optimization identifies decisions that perform adequately across multiple scenarios. Adaptive management builds in learning mechanisms that update strategies as new information arrives.

Real options analysis—treating strategic decisions as options with value in uncertainty—proves valuable for VUCA navigation. Rather than requiring immediate commitment to single paths, real options frameworks value flexibility and the ability to adjust as uncertainty resolves. This applies directly to environmental strategy: investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, and natural capital restoration maintain optionality while hedging against multiple adverse scenarios.

Behavioral economics contributes to VUCA analysis by recognizing that decisions under uncertainty involve cognitive biases and emotional responses beyond rational calculation. Overconfidence bias leads to underestimation of tail risks; availability bias causes overweighting of recent events; ambiguity aversion creates preference for known risks over unknown risks. Understanding these biases improves policy design by accounting for actual human decision-making rather than idealized rationality.

Complexity science approaches—network analysis, agent-based modeling, and systems dynamics—enable analysis of emergent properties and feedback loops absent from traditional equilibrium models. These approaches prove particularly valuable for understanding how local disruptions propagate through interconnected systems and how feedback loops amplify or dampen initial shocks.

FAQ

What distinguishes VUCA from traditional economic uncertainty?

VUCA encompasses not only uncertainty about outcomes but also volatility (rapid price movements), complexity (numerous interconnected variables producing non-linear effects), and ambiguity (multiple plausible interpretations of identical data). Traditional economic uncertainty focused primarily on forecasting challenges; VUCA analysis explicitly addresses structural characteristics of modern economies that make prediction difficult independent of data quality.

How do environmental factors contribute to VUCA conditions?

Environmental volatility (extreme weather, crop failures) directly creates economic volatility. Uncertainty about ecological tipping points introduces deep uncertainty where catastrophic outcomes become possible. Complexity arises from interconnections between environmental and economic systems. Ambiguity emerges from disagreement about appropriate responses to environmental challenges and conflicting interpretations of climate economics data.

Can economies eliminate VUCA conditions through better policy?

Complete elimination of VUCA appears impossible given technological disruption, geopolitical complexity, and ecological system dynamics. However, effective policy can reduce unnecessary volatility, improve institutional capacity for adaptation, build redundancy and resilience, and create transparency that reduces ambiguity. The goal shifts from eliminating VUCA to developing capacity for navigating inherent uncertainty effectively.

What role does technology play in VUCA navigation?

Technology provides tools for improved information (real-time data, advanced modeling), increased adaptability (flexible production systems, distributed infrastructure), and new solutions to environmental constraints (renewable energy, alternative proteins). However, technology also introduces new complexities and dependencies. Effective VUCA navigation combines technological capability with institutional adaptation and governance mechanisms that ensure technology serves resilience objectives.

How should investment strategy change in VUCA environments?

VUCA-conscious investment emphasizes diversification, redundancy, flexibility, and optionality. Rather than concentrating resources in high-growth but vulnerable strategies, resilient investment maintains multiple options and avoids irreversible commitments to single paths. Environmental considerations become central—investments in renewable energy, natural capital restoration, and climate adaptation provide resilience while addressing ecological constraints.

Why do economists disagree about VUCA responses?

Ambiguity about causes and appropriate responses creates legitimate disagreement. When inflation could result from demand excess or supply constraints, different interpretations suggest different policies. When climate policy could emphasize emissions reduction or adaptation, different frameworks suggest different priorities. These disagreements reflect not incompetence but genuine ambiguity that cannot be resolved through additional data alone—they require value judgments about priorities and risk tolerance.